Editor’s Note: This CNN series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over subject matter, reporting and frequency of the articles and videos within the sponsorship, in compliance with our policy.

On the northern edge of the Rub al-Khali, there are secrets buried in the sand.

The vast 250,000 square miles (650,000 square kilometer) desert on the Arabian Peninsula is known as “The Empty Quarter.” And to most, aside from waves of ocher dunes, it does look empty.

But not to artificial intelligence.

Researchers at Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi have developed a high-tech solution to searching huge, arid areas for potential archaeological sites.

Traditionally, archaeologists use ground surveys to detect potential sites of interest, but that can be time-consuming and difficult in harsh terrains like the desert. In recent years, remote sensing using optical satellite images from places like Google Earth has gained popularity in searching large areas for unusual features — but in the desert, sand and dust storms often obscure the ground in these images, while dune patterns can make it difficult to detect potential sites.

“We needed something to guide us and focus our research,” says Diana Francis, an atmospheric scientist and one of the lead researchers on the project.

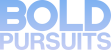

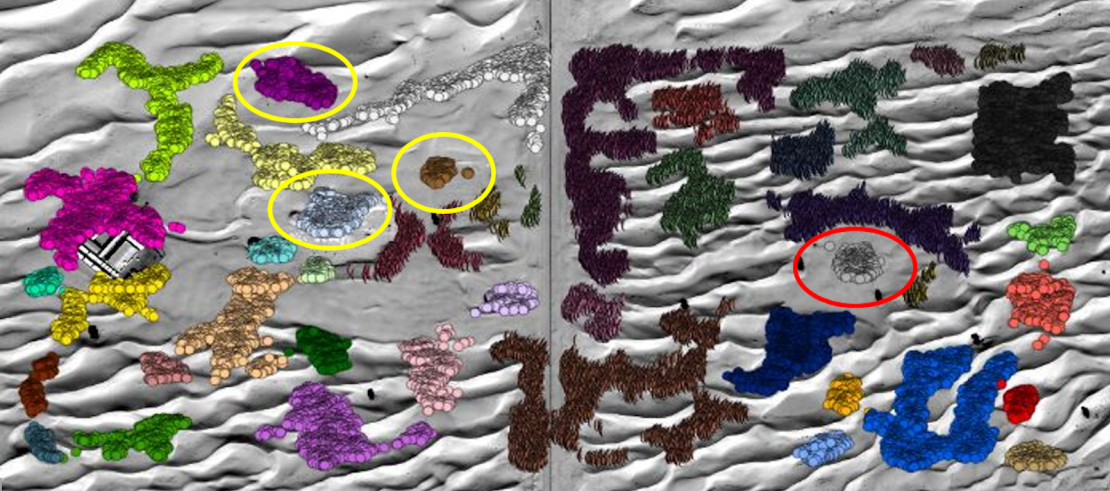

The team created a machine learning algorithm to analyze images collected by synthetic aperture radar (SAR), a satellite imagery technique that uses radio waves to detect objects hidden beneath surfaces including vegetation, sand, soil and ice.

Neither technology is new: SAR imagery has been in use since the 1980s, and machine learning has been gaining traction in archaeology. But the use of the two together is a novel application, says Francis, and to her knowledge, is a first in archaeology.

She trained the algorithm using data from a site already known to archaeologists: Saruq Al-Hadid, a settlement with evidence of 5,000 years of activity that is still being uncovered in the desert outside of Dubai.

“Once it was trained, it gave us an indication of other potential areas (nearby) that are still not excavated,” says Francis.

She adds that the technology is precise to within 50 centimeters and can create 3D models of the expected structure that will give archaeologists a better idea of what’s buried below.

In collaboration with Dubai Culture, the government organization that manages the site, Francis and her team conducted a ground survey using a ground-penetrating radar, which “replicated what the satellite measured from space,” she says.

Now, Dubai Culture plans to excavate the newly identified areas — and Francis hopes the technique can uncover more buried archaeological treasures in the future.

Expediting “tedious” work

Using SAR imagery is not common in archaeology, due to its cost and complexity.

But the use of it to identify buried sites is “really exciting,” says Amy Hatton, a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology, who is researching deep learning models to detect archaeological structures in northwest Saudi Arabia.

Hatton notes that, by using SAR imagery, which bypasses the problem of light scatter from dust particles, Francis and her team solved technical details that make remote sensing difficult in desert regions.

Khalifa University isn’t alone in using artificial intelligence to detect potential sites.

Amina Jambajantsan, another PhD student at the Max Planck Institute, is using machine learning to speed up the “tedious job” of searching through high-resolution drone and satellite images for potential sites of interest. Her project, which focuses on medieval burial sites in Mongolia — a country of more than 1.56 million square kilometers, nearly the size of Alaska — has uncovered thousands of potential sites that Jambajantsan says she and her team could never have found on the ground.

Jambajantsan says that while the cost and computational demandsof SAR imagery could be a barrier to usage for a lot of researchers, the method is valuable for desert regions where other technologies struggle — and is one she would consider for the Gobi Desert in Southern Mongolia, where her “normal optical imagery” is not yielding results.

Man vs. machine

Machine learning is finding more and more applications in archaeology, although not all researchers are excited about it.

“There are two distinct belief systems,” says Hugh Thomas, an archaeology lecturer at the University of Sydney and co-director of the prehistoric AlUla and Khaybar excavation project in Saudi Arabia. On one side, people are pursuing technological solutions like AI to identify sites; on the other, those who believe you need a “trained archeological eye” to identify structures, he explains.

While technology could help identify and monitor archaeological sites — particularly ones under threat from land use changes, climate change, and looting — Thomas is wary of over-reliance on it.

“The way that I would like to use this kind of technology is on areas that perhaps have either no or a very low probability of archaeological sites, therefore allowing researchers to focus more on other areas where we expect there to be more found,” says Thomas.

Unearthing the past

The real test — and hopefully, validation — of the technology will happen next month when excavations begin at the Saruq Al Hadid complex, of which only an estimated 10% has been uncovered across a 2.3-square-mile (6.2-square-kilometer) area, according to Dubai Culture.

If archaeologists find the structures the algorithm has predicted, Dubai Culture plans to use the technology to unearth more sites.

Francis and her team published a paper on their findings last year, and they are continuing to train the machine learning algorithm to improve its precision, before expanding its use.

“The idea is to export (the technology) to other areas, especially Saudi Arabia, Egypt, maybe the deserts in Africa as well,” she says.

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Amina Jambajantsan’s name