A tiny songbird, no bigger than a teacup, is back in the New York City region after a 60-year absence.

A tiny songbird, a massive landfill and a glimmer of hope

Unmute for best experience with sound

Scroll down

More than 60% of all grassland habitats in North America have been lost, according to the 2019 North American Grassland and Birds Report by the National Audubon Society. Much of it is due to agricultural conversion and other human development, it said. In the largest swath of major grasslands left, the Great Plains — stretching from Alberta and eastern Montana down through the central US — less than 2% of the remaining habitat there is strictly protected and by federal agencies as of 2016, one analysis found.

“The habitat is the thing that defines where that bird is,” according to Andrew Farnsworth, a visiting scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. When grasslands disappear or get drained, the birds vanish too, as happened in New York City.

But the sedge wrens, listed as threatened in the state of New York, are back in Freshkills Park on Staten Island. We set out in September to catch a glimpse of the mysterious bird, wandering through the rolling hills, led by José Ramírez-Garofalo, the park manager for science and research development.

There isn’t a lot of habitat like this in our region. In fact, this is pretty unique in general for all of New York state. This is undisturbed temperate native grassland.

It’s a serene expanse, a 2,200-acre oasis with the glass towers of Manhattan gleaming in the distance. Below our feet, slowly decomposing, were millions of tons of garbage from what was once the world’s largest landfill.

Sedge wren

Cistothorus stellaris

Meet the sedge wren

Audio transcript:

undefined

Sedge wrens are small, compact songbirds, measuring between 3.9 to 4.7 inches long

…with a wingspan up to about 5 inches across.

They weigh about 0.3 oz.

They use their slender bills and long legs to forage in low vegetation for spiders and insects.

You may spot a sedge wren by looking for its streaked pattern of black and brown on its back. Its round belly and throat are a lighter, peachy color.

The sedge wrens are among the most nomadic birds in North America, according to Farnsworth, which means they can visit one year and be completely absent the next.

They mostly nest in the Upper Midwest and parts of Central Canada from May through August, according to Farnsworth, who is an expert in bird migration. By October, they head south toward the Gulf Coast for the winter.

It’s likely that the wrens had been flying over New York for the last 60 years, but not nesting because there was no available habitat, Farnsworth said.

But once other birds, particularly grasshopper sparrows, started breeding on the reclaimed land in Freshkills, it signaled to the passing sedge wren that it could also thrive in the park, according to Ramírez-Garofalo.

Sedge wren, as a nomadic species, require specific conditions to nest successfully. That means any kind of habitat loss — either caused by humans or by the climate crisis — can affect the population.

While it was an active landfill, Fresh Kills received as much as 29,000 tons of trash per day, including debris from the World Trade Center after 9/11.

It opened in 1948, and by 1955 Fresh Kills was the largest landfill in the world, according to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Now, Freshkills Park, renamed as one word, is one of the largest grassland habitats in the region, and includes about 1,000 acres of reclaimed grasslands, according to the park.

Once it opens fully to the public in 2036, it will be almost three times the size of Central Park and the largest park developed in New York City in more than a century, the city said. The first phase of the North Park opened to the community this year.

Since the revival of the grasslands, it’s been home to the sedge wren and several other grassland bird species.

Hear more about species that came back to Freshkills from NYC Urban Park Ranger Grayson Manzi

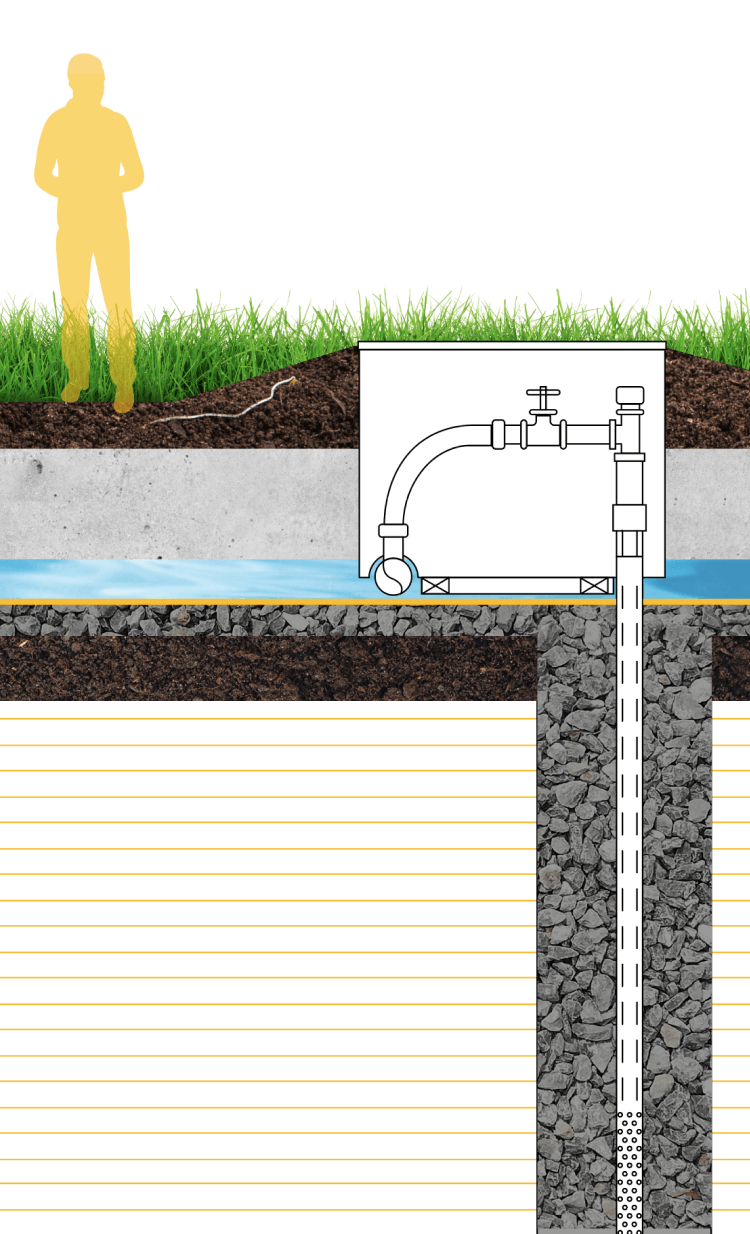

How the landfill was turned into the park

Each mound of waste is capped using various layers of materials, measuring from three to 12 feet deep, according to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

A soil barrier layer and gas vent layer sit in between the waste and an impermeable plastic liner, NYC Parks says. A drainage layer goes on top of the liner to help direct water to stormwater chutes and away from the waste. Then comes sandy soil on top of the drainage layer before another layer of planting soil at the top.

Decomposing waste creates both a gas and liquid byproduct. The city says the byproducts will eventually completely drain from the mounds, but that’s expected to take at least 30 years.

Years of work and millions of dollars of investment have transformed these mountains of trash into a peaceful green space.

On August 6, 2020, Ramírez-Garofalo and other researchers spotted something no one has seen since 1960 in New York City: three pairs of sedge wren nesting among the tall grasses and other native plants.

“We just out of nowhere, just heard one of the birds singing and we all just kind of looked at each other like, you know, OK this is very strange. This is a species that we definitely would not expect to see here especially,” said Ramírez-Garofalo, who published research about the discovery with Dr. Shannon Curley and Dr. Cait Field. He and Curley now lead the current research at the park.

“We were very excited but over the course of many weeks and throughout the months we were just trying to learn as much as we could about the history of sedge wrens in the area,” he added. It was a big moment for the park and for the researchers – the birds had been absent from Staten Island since 1943, he said.

The wrens laid eggs on September 16 in the East Mound area and both mom and babies left the park by October 11, according to the research.

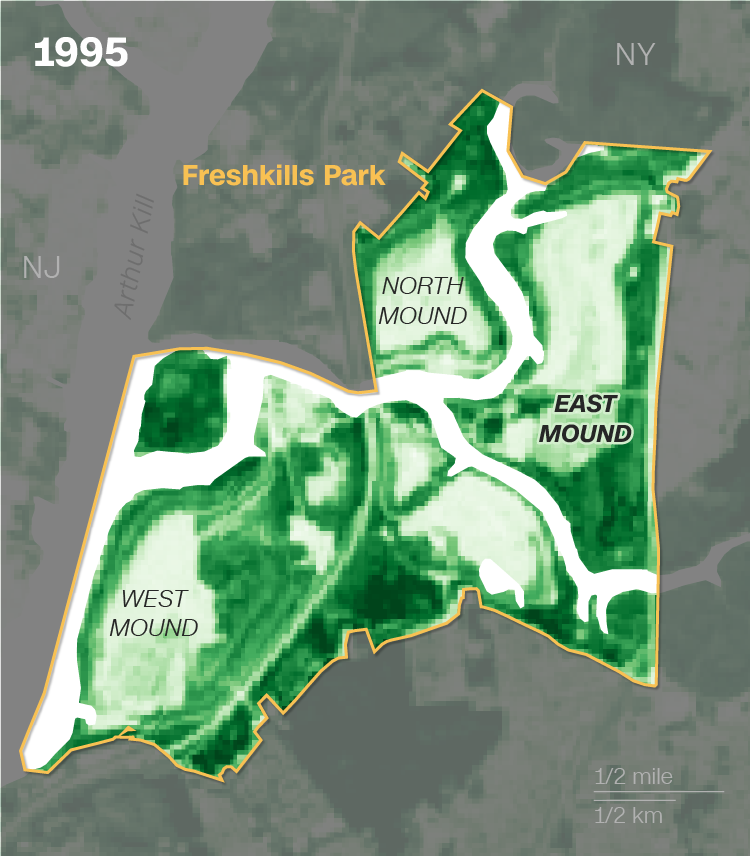

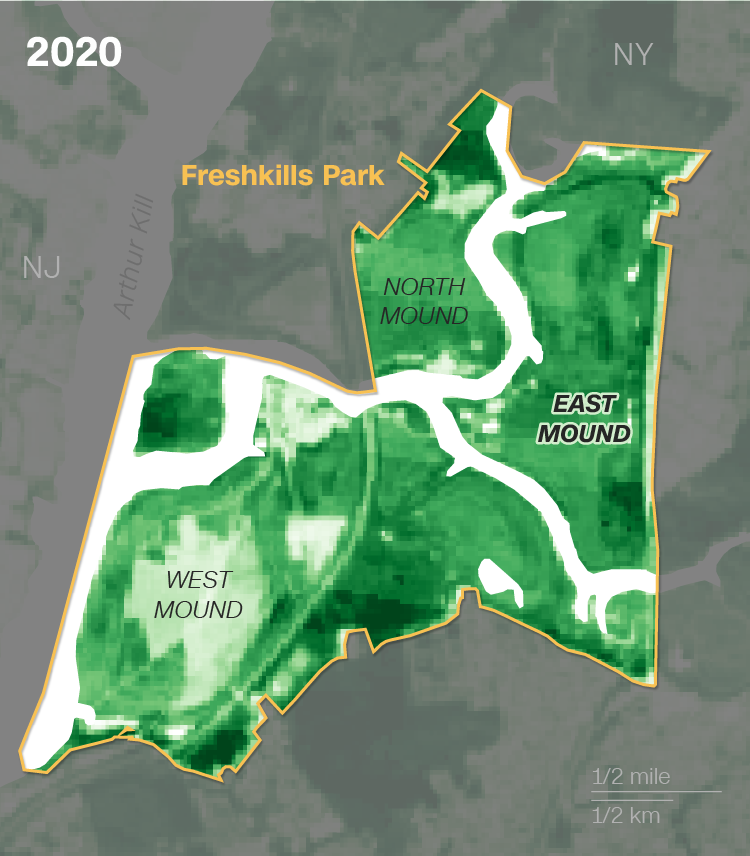

In 1995, a year before the landfill was originally scheduled to close, much of the park was an unsuitable habitat for grassland birds. But by 2020, when the sedge wren was first spotted on the East Mound, the area was covered in dense vegetation.

The East Mound, seeded with a native warm-season grass mix, is more than 400 acres of continuous, undisturbed grassland — something that is unique for all of New York state, Ramírez-Garofalo said.

The East Mound is especially favorable to the sedge wren because the grasses stay damp throughout the summer. The center of the mound slopes down, preventing a lot of the water from completely draining, according to Ramírez-Garofalo.

All of these factors also created conditions for the abundance of native arthropods which are the food source for the grassland birds.

The sedge wrens were back in greater numbers in 2021, with eight pairs spotted in the park and one or two of those pairs nesting successfully, Ramírez-Garofalo said. No pairs nested in 2022 because of drought conditions, he said.

Last month as we watched, Ramírez-Garofalo was searching for another glimpse of the nomadic, little bird.

After stringing up a long, thin net, attached to metal poles affixed in concrete bases, he and his colleague Dr. Shannon Curley held their breath. Two speakers, attached to each side of the net, play various bird calls, hoping to lure one into their trap.

They pointed their binoculars to the sky, and Curley, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, identified dozens of bobolink and an osprey flying overhead.

Suddenly a savannah sparrow, the most abundant species in the park, hit the net. Ramírez-Garofalo sprinted toward the tangled bird. Time is of the essence and handling the bird for a few seconds too long, especially in warmer weather, could be deadly.

With the whole process lasting just a few minutes out of the tailgate of his truck, Ramírez-Garofalo put a small, silver metal band around the sparrow’s leg. Curley handed him tools and wrote down notes and Ramírez-Garofalo measured its wingspan and determined its age before gently putting the bird face down into a canister to weigh it. He also blew on the sparrow’s chest to check how much fat it had — important for determining how ready the bird is to migrate.

Though they didn’t band a sedge wren that day, Ramírez-Garofalo said the birds were spotted at the park this year. However, he and Curley don’t know if they nested.

Bird banding tracks what the birds are up to and where they are breeding in the highest density.

“When we start to see birds that are banded coming year after year but they’re also coming to the same areas, those are areas that we want to make sure are being disturbed less. We want to make sure those are areas that we’re really monitoring,” Ramírez-Garofalo said.

Frequent returners also are a good indication that the habitat is to the bird’s liking, he said.

The goal is to conserve the habitat so that birds keep coming back. But keeping the integrity of the 400 acres of grassland on the East Mound is not easy.

Invasive species are the biggest problem, Ramírez-Garofalo said. The Lespedeza bush clover is already growing in clumps between the tall native grasses and sedges. The diversity of arthropod species that grassland birds eat is much lower in places where there is bush clover, making it less favorable for nesting, he said.

Grasslands and invasive species are usually managed using fire, but since Freshkills is in New York City and is a site of a capped landfill, controlled burns are not an option. That means everything invasive must be pulled out by hand — a tall order for such a big area of open habitat, Ramírez-Garofalo said.

We hope that over time and as we get more funding, as people start to really develop a kind of like a stewardship connection to the park, we can bring people in, bring volunteers in, and remove a lot of the invasive species.

Until a multi-agency conservation plan is finalized and put in place, the East Mound will be highly restricted to visitors to minimize disturbances to the bird, according to Ramírez-Garofalo. Right now, there is no access since it won’t be open to the public for about a decade.

Eventually, “We want to make sure people have an appreciation for the species that are here so that we can conserve them,” Ramírez-Garofalo said.

Combatting the habitat loss that drove away the sedge wren in the first place is a complex challenge.

“It’s highly critical that we maintain the areas that are protected currently and try to restore places that could be habitat,” said Dr. David Pilliod, a supervisory research ecologist at the US Geological Survey. Habitat loss could cause the extinctions of more species, he said.

Right now, 34% of plants and 40% of animals are at risk of extinction across the country, according to a report published by NatureServe, a non-profit conservation organization. About 41% of ecosystems are at risk of collapse, with temperate grasslands among the most threatened, it said.

One big challenge in the US is that much of the land is privately owned, Pilliod said, meaning there need to be partnerships between landowners, tribes and government agencies in order for restoration and conservation efforts to be successful.

More than twice as much habitat loss for endangered species has occurred on non-protected private lands compared to federally protected lands, according to a study published in 2020 by scientists at Tufts University and the non-profit conservation organization Defenders of Wildlife, among others.

Of the more than 2.4 billion acres of US landmass, about 866 million acres are managed by federal, state or local governments, according to the USGS Protected Areas Database of the US. About 728 million acres are protected in some way, or about 29%, according to the data. Much of those protected lands are on the West Coast and across the Rockies, maps show.

Driven by climate change, habitats are now threatened increasingly by wildfires, flooding, drought and invasive species, Pilliod said.

Freshkills can be an example for the rest of the country. The reappearance of the sedge wren is a “glimmer of hope,” Pilliod said, proof that if humans restore habitats, biodiversity will respond in a positive way.

Other reclaimed land can also be transformed to attract birds and other animals. According to a study published in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology in 2006, reclaimed surface coal mines in the Midwest proved to support many grassland and savanna bird species.

The study, which looked at the 1999 and 2000 breeding seasons, found that at least 31 bird species successfully nested in the reclaimed habitat in a way that was comparable to other non-mined grasslands. Researchers say that reclaimed mines, like reclaimed landfills, can provide a “unique opportunity in avian conservation, especially for the management of grassland birds.”

The critical nature of habitat loss is being recognized at the federal and global levels. In the United States, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law gives the Department of the Interior $1.4 billion over five years for ecosystem restoration.

Globally, the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration aims to reverse the destruction of ecosystems in partnership with organizations and member states. It runs through 2030 which is “the timeline scientists have identified as last chance to prevent catastrophic climate change,” it warns.

Healthy ecosystems are vital to humanity, according to both Pilliod and Farnsworth. Biodiversity helps with pest control, storing carbon, preventing erosion and providing pollinators for agriculture.

“As humans, we need a connection to the world around us to manage it properly and to invest in it,” Farnsworth said. “You think about the technological advances in this world, it's still really important to just open your eyes and go out and collect data and see patterns like this and understand what they mean,” he added.

Not unexpectedly, the sedge wren was elusive during our trip to Freshkills. But Ramírez-Garofalo is committed to tracking the songbird and the other species who have made their home on this beautiful grassland created over a mountain of trash.

We’re responsible for their declines and so we do have a responsibility to be good stewards to the planet... Especially in urban areas where we have really good opportunities, a very unique opportunity, to conserve them.