EMPLOYED BY CHINA

It’s often assumed that the Chinese in Africa ‘bring their own’ and don’t hire locals. In Ethiopia, that’s not the case -- but will it lift the country out of poverty? Words, video and images by Jenni Marsh, CNN

The assembly line at Huajian International Shoe City, Addis Ababa.

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia — Zhang Huarong points out of his office window to a bleak block of grey portacabins at the Huajian International Shoe City, in Addis Ababa. “That is what I lived in for six months when I came to Africa,” he says. “I am 60 years old. Back in China, I am a wealthy man -- my house in Dongguan even has a swimming pool. But I chose to come here and do something very difficult.”

In 2011, this self-made textile tycoon from Jiangxi province became one of the first Chinese entrepreneurs to heed the call of Ethiopia’s then-Prime Minister Meles Zenawi to open a factory in his country. Within three months, Huajian was producing footwear for giants such as Nine West, Guess and, later, Ivanka Trump’s fashion line, before it closed.

“This is something God is telling me to do,” Zhang (pictured below) says, framing himself as a 21st-century manufacturing missionary whose goal is to create more than 100,000 jobs in the poorest parts of Africa. Rwanda is next. “In China, no one wants to make shoes anymore,” he adds.

Ethiopia is undoubtedly one of the continent’s poorest countries, but that’s changing. In the decade leading up to 2016, Ethiopia’s economy swelled 10% a year making it the fastest growing in Africa. And with 100 million people, 70% of whom are under age 30, it also has the continent’s second-largest population. That’s both a massive demographic dividend and a real risk: with unemployment at 16.8%, jobs are urgently required.

Businessmen like Zhang are seen as the country’s ticket out of poverty. Huajian employs 7,500 local workers at its two enormous factories in the Addis Ababa region. “As long as they have the right skills and training, Africans are just like Asians and Europeans,” he says.

Huajian makes shoes exclusively for American clients.

As one of the biggest Chinese employers in Ethiopia, Huajian has attracted intense scrutiny. Reports last year of poor working conditions at the firm’s Guangdong factory, in China, and rock bottom wages in Addis Ababa saw two customers, one of whom was Trump, jump ship.

While many of the criticisms were valid, Huajian is operating in an environment of deep Western suspicion of the Chinese in Africa. In March, Rex Tillerson, then secretary of state, told leaders at the African Union, in Addis Ababa, that Chinese investors “do not bring significant job creation locally.” His comments echoed warnings about neo-colonialism in Africa and Chinese labor importation by Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, respectively.

“China is a rising economy, and it’s going to be the global number one by 2030 latest,” says Arkebe Oqubay, a senior government official and architect of much of Ethiopia’s industrialization strategy. “There’s always rivalry when a great power diminishes. But we as the Africans are the ones to say if we are benefiting from China. We don’t need a witness.”

About 4,000 Ethiopian workers are employed at the Huajian International Shoe City, Addis Ababa.

‘Even my father doesn’t like being a farmer’

When Emaway Gashaw was 18 years old, she got on a bus and waved goodbye to her large family of coffee farmers. The journey from Jimma, in western Ethiopia, to Addis Ababa took 10 hours. She wound up in Jemo, a suburb of the capital that a decade ago was countryside but today is dotted by concrete condos housing rural migrants looking for work, including her elder cousin. “When I got here, I didn’t have any opportunities so I took this job,” she says. Emaway is a leather skiver at the Huajian International Light Industry City, a 1.5 million-square-meter industrial park that, will eventually provide housing, hospitals and schooling onsite, employ 100,000 workers, and within 10 years create $4 billion in revenue, according to the company.

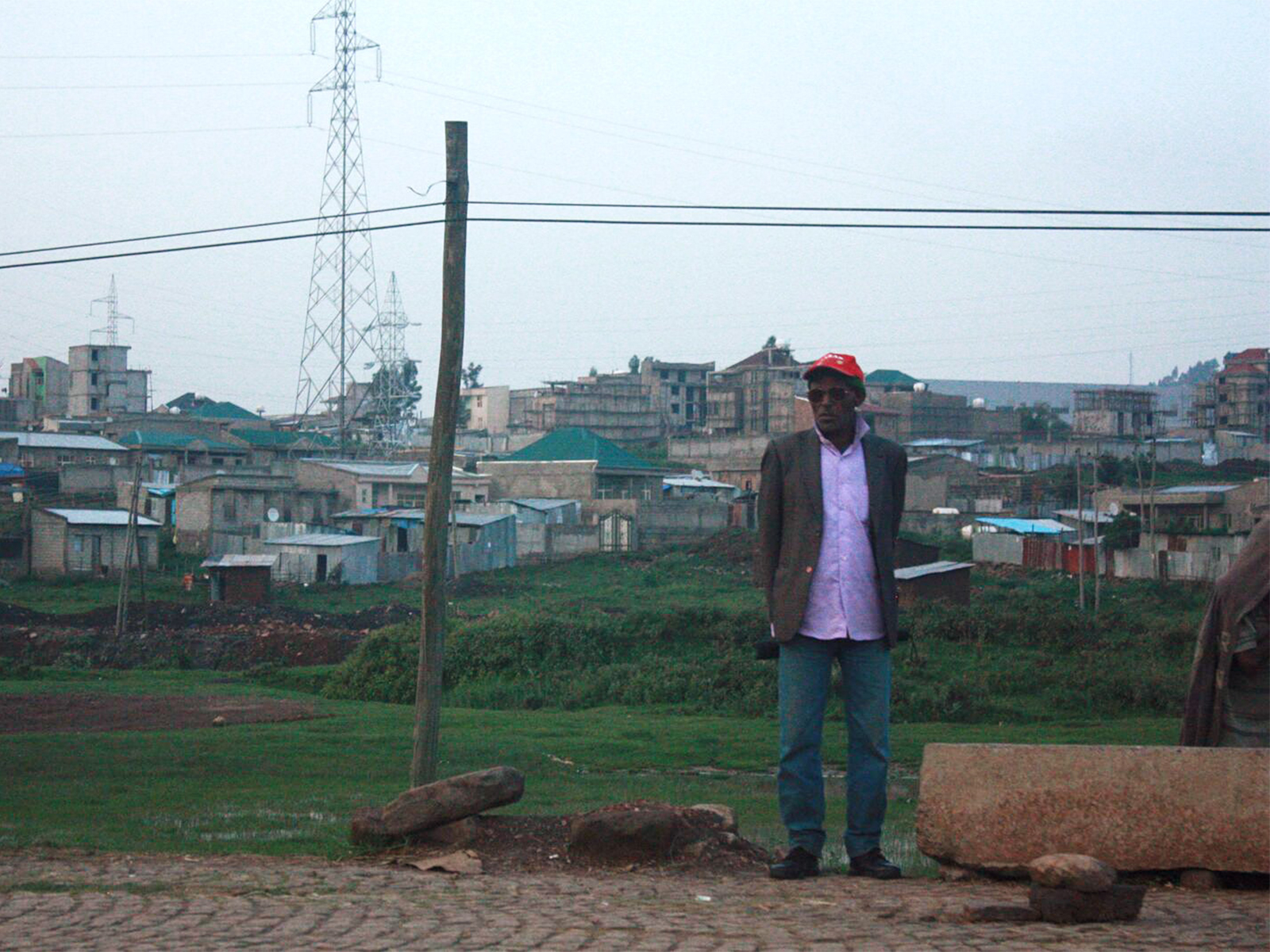

The Jemo area of Addis Ababa is becoming increasingly urban.

From 8 a.m. until 5 p.m., Emaway forms part of a sprawling assembly line inside a brightly lit, air-conditioned shed that looks like a giant aircraft hangar. But her wages allow for little. “I get paid 1,200 birr ($44) a month with overtime,” she says. “After rent and food, there is nothing left. My cousin has to support me.”

Emaway is one of the lowest-paid workers at the factory. Getachew Tilanun, 20, is from a family of maize farmers in Welega, where Ethiopia borders South Sudan in the west. After working at the factory for two years, he has been promoted twice and now earns 2,500 birr (about $90) a month, and receives three meals a day and the chance to live onsite for subsidized rent.

Unlike 90% of International Labour Organization member states, Ethiopia has no minimum wage. The international poverty line is about $57 a month.

Emaway Gashaw, 18 years old, has worked at Huajian for nine months.

“For my wage, I have a lot of responsibility,” he says, explaining that he oversees 100 workers, including 11 line supervisors. “If they make mistakes, my wages get docked.” Getachew has taught himself to speak Chinese to give himself “unique” employment skills. “I tried to find out everything I could about China on the internet,” he says. “When I saw Asian people, I just tried to speak to them.”

His work is tough, but the alternative is worse. “Even my father doesn’t like being a farmer,” Getachew says. “It’s the job of the very uneducated.”

Just 1% of the 4,000 workers at the Jemo factory are Chinese, says Bonn Liang, a manager who was headhunted from Dongguan one year ago. "But in the future, we will all go back to China,” he adds.

That’s already happened at the Sino-Ethiop Associate pharmaceutical factory in Dukem, south of Addis. A joint venture between two Chinese and one Ethiopian firm, the facility has 177 employees, only one of whom is Chinese. “In our first year, some Ethiopian workers were sent to China for training, and about 50 Chinese experts came here,” says Andrew Shegaw, the factory manager. “Now we are 100% independent.” The factory employs Ethiopian pharmacists, engineers, and electricians, who received workplace training from the Chinese to supplement their academic knowledge.

A worker at the Sino-Ethiop Associate pharmaceutical factory in Dukem.

Contrary to popular belief, these scenarios are not unusual. A groundbreaking McKinsey report last year, which surveyed more than 1,000 Chinese companies in construction, manufacturing, trade, real estate, and services in eight African countries, including Ethiopia, found that on average 89% of employees were African. Several million African jobs had been created by China on the continent. Nearly two-thirds of Chinese companies provided skills training, while half offered apprenticeships, and a third had introduced a new technology.

It was the first time a large-scale dataset on Chinese hiring practices in Africa had been made available, and it rebutted the criticisms voiced by Tillerson. “I believe that (his claim) was very short-sighted,” Arkebe says. “It’s hard to believe a secretary of state was misinformed.”

‘It’s a matter of patriotism … and ego’

The China-Africa relationship has only made headlines in the past decade, but it can be traced back to the mid-20th century when Beijing began befriending newly independent states. In 1968, China -- then a poor nation -- spent the equivalent of $3 billion in today’s money on constructing the Tanzam Railway, which linked landlocked Zambia to the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. Britain, the United States and the United Nations had all passed on the project. China’s help didn’t come for free. At that time, Taiwan -- not Beijing -- held a coveted seat on the UN Security Council. When China reclaimed that seat in 1971, 26 of the 76 votes came from Africa.

Fast forward a few decades, and China has pulled off a jaw-dropping economic boom. “African leaders saw China go from being an economy on its knees, with a poor, rural, uneducated population, to the second-largest economy in the world. That’s concrete evidence that magic can happen,” says Solange Chatelard, academic and research associate at the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium.

By the late 1990s, Africa had dropped off the radar for the West, which associated the continent with poverty and the AIDS crisis, says Chatelard. “That’s exactly when China was plotting its comeback.” In Africa, China saw an opportunity for diplomacy and trade.

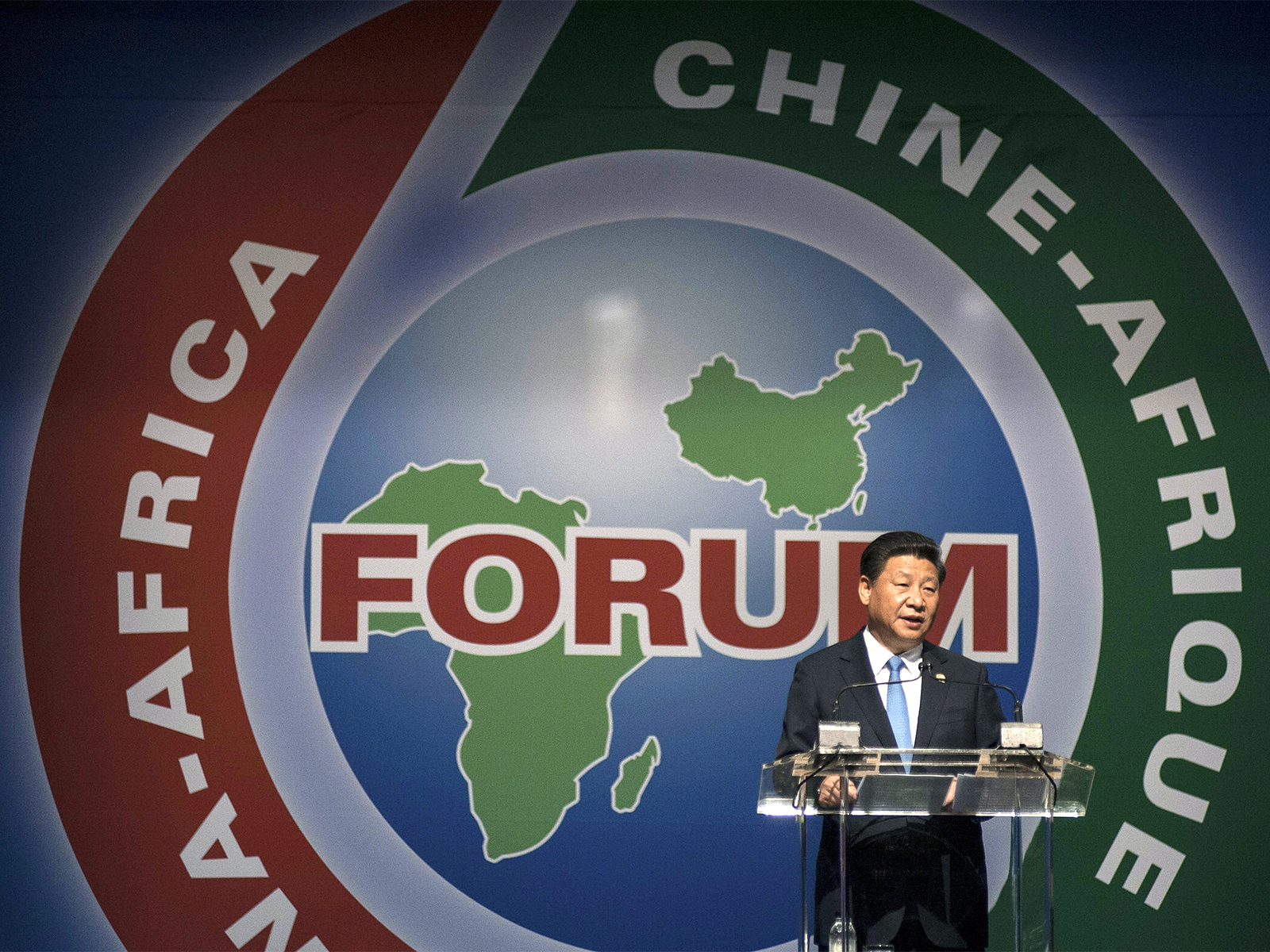

In 2000, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) was launched in Beijing and has since become a triennial deal-making powwow between China and all African states. At FOCAC 2015, China pledged to invest $60 billion in Africa over the next three years.

Chinese president Xi Jinping speaks at the 2015 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in South Africa. (Ihsaan Haffejee/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Claims that the Chinese are “colonizing” Africa, however, by exploiting its natural resources, land, and labor, are insulting to the victims of European colonization, which was based on spiritual control, brutal force and slavery, Chatelard says.

The Chinese, she explains, play to the local labor laws. In countries such as Angola and Algeria, for example, where the local government doesn’t force the use of local labor, Chinese firms have taken the easiest road and used their own countrymen.

Meles decided early on that China could be useful in two ways. Firstly, in generating manufacturing jobs to mechanize its workforce and encourage knowledge transfer. Secondly, in building infrastructure, such as the Addis Ababa-Djibouti rail line, which cut the journey time for whisking goods from landlocked Ethiopia to the sea from days by road to 12 hours.

Arkebe clarifies that Ethiopia doesn’t take Chinese loans for buildings such as football stadiums, unlike Zimbabwe, Senegal, and Angola.

The Chinese-built African Union.

The Addis Ababa Light Rail system -- built by the Chinese.

“The fact that we didn’t encounter colonialism is important,” says Belachew Fikre, commissioner of the Ethiopian Investment Commission, explaining his countrymen’s mindset when dealing with foreign powers. Ethiopia is the only African nation to have never been colonized, bar a brief muscle-in by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini between 1935 and 1941. “It’s a matter of patriotism and ego, too. You cannot order an Ethiopian about,” he says.

Still, getting Chinese companies to invest wasn’t easy at first. Conditions in Ethiopia 10 years ago were so poor and transportation links so bad that “to be honest, I did not think of investing here,” says Zhang. It took Meles personally deploying his powers of persuasion to convince Zhang to open a factory in time for the opening ceremony of the African Union headquarters in January 2012, he says. The $200 million futuristic building was one of Beijing’s largest gifts to Africa since the Tanzam railway. One year later, Chinese president Xi Jinping unveiled his Belt and Road initiative, a vast collection of interlinking trade deals and infrastructure projects throughout Africa, as well as Eurasia and the Pacific.

The Commercial Bank of Ethiopia will be the tallest building in Ethiopia when completed by China State Construction Engineering Corporation in 2020.

No McDonald’s in Ethiopia

Today, it’s not only the Chinese who have woken up to “Made in Ethiopia.” In the lakeside town of Hawassa, the weekend playground of the Addis elite, a huge industrial park opened in 2016. American clothing giant PVH, whose brands include Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, and H&M, takes up a chunk of the 400,000 square-meter space.

Hawassa is one of 30 industrial parks that will have opened in Ethiopia by 2020. Mostly Chinese-built, these “areas of excellence” echo the Special Economic Zone model that turned Shenzhen into a manufacturing powerhouse within one generation.

As such, Ethiopia has been called the “China of Africa,” and there are some undeniable parallels. The Solomonic dynasty, which ruled Ethiopian until Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown in 1974, traced its roots -- somewhat suspectly -- directly back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba in 10th century BC; China claims to have 5,000 years of continuous history.

Emperor Haile Selassie meets Mao Zedong, Chairman of China’s Communist Party, in London in 1960. (Keystone Press Agency/ZUMAPRESS)

In modern times, both countries had huge populations to mobilize into a poverty-alleviating workforce, endured a brutal Communist dictator, and have operated a notorious Great Firewall (the Ethiopian government frequently just turns the internet off). Neither tolerates dual citizenship, but Ethiopia offers its large diaspora an Ethiopian Origin card, just as China proffers the Home Return Permit for those of Chinese descent, stressing a sense of ethnic identity that goes beyond nationality.

Ethiopians bristle at the idea they are imitating China. “I will never characterize Ethiopia as a Chinese model,” Belachew says. Delegates toured a range of industrialized nations to learn from their mistakes and inform Ethiopia’s economic policy, he adds. “We looked at Chinese-built parks in Nigeria, and they were a disaster,” says Arkebe. The zones lacked an energy supply, hadn’t been woven into an economic strategy and, he says, “created peanuts” -- a claim the Lekki Free Zone rebutted in an email to CNN.

“I will never characterize Ethiopia as a Chinese model.”

-- Belachew Fikre, commissioner of the Ethiopian Investment Commission

Ethiopia took note. Hawassa, which cost $300 million to build, is an eco-friendly facility with a reliable power supply, streamlined on-site visa and banking services and -- as in many other Ethiopian industrial parks -- amazing tax breaks: companies enjoy a 10-year tax holiday, expatriate staff pay no income tax for five years and exports are duty free.

The benefits are so unbelievable it is hard to see how Ethiopia will win.

Arkebe says the parks are designed to generate jobs not revenue. “For every manufacturing job created, 2.2 indirect jobs emerge,” he says. Hawassa by itself could generate 46,000 roles. Unlike in West Africa, where Chinese-owned shops are common, Ethiopia doesn’t give retail licenses to foreign investors. McDonald’s and Starbucks are yet to arrive here.

On the ground, both Hawassa and Huajian have struggled with a workforce striking over low pay. “The workers here are still only a third as productive as in China,” says Zhang. Ayele Gelan, an Ethiopian economist at the Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, says wages paid by the likes of Huajian are not abnormal, it’s just that Ethiopia has an “abysmally” low minimum wage for a developing country. An entry-level teacher would get paid seven times more in Nairobi, Kenya, than in Addis Ababa, for example, despite the cost of living in the Ethiopian capital being much higher, he says.

Patrick Belser, senior economist at the International Labour Office in Geneva, ILO, says his organization is preparing recommendations on an appropriate minimum wage for the Ethiopian government, which would address problems of absenteeism and high turnover. “It would be a win-win situation to have higher wages that increase the motivation and productivity of the workers,” he says.

Where the Chinese management reside.

The living quarters of Huajian’s Ethiopian staff.

At Huajian, as the day ends, workers pile into the giant canteen where the Chinese managers tuck into noodles and stir-fried meat, while the Ethiopian workers eat stews from injera bread in a separate area. Afterward, the locals file back to homes that resemble shipping containers, while the Chinese retire to quaint wooden chalets, which were imported from Canada. Does segregation like this, while perhaps unavoidable, fuel resentment?

Zhang pauses. “You know that 50 years ago, my family did not have enough money for food or even clothes. We were so poor. I started my company with three sewing machines in a very small workshop.” On the flatscreen TV in his office, Zhang fires up the video to a song titled “China-Africa,” which he says a Huajian employee wrote. A Chinese operatic vocalist sings:

“Huajian comes,

The Chinese and Africans work hand in hand like brothers,

The African dream of the African people ...

To build the One Belt, One Road dream.

Hold high the torch of hope!

Huajian comes.”

It is almost evangelical and screened without a shred of irony.

When FOCAC reconvenes this September in Beijing, most African heads of state are expected to attend, and Abiy will be asking Beijing to send more Zhangs his way, according to ministers. “It’s not easy for Chinese companies to come to Africa,” Arkebe says. But with Africa’s population projected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050, he believes it is essential for countries like his to attract investment now to ensure political stability on the continent. “Made in Ethiopia” in short, he says, is a label the whole world should get behind.

Editors: Stephanie Busari, Brad Lendon and Jo Parker, CNN