A perfectly twirled bite of spaghetti hangs off a fork mid-air. Next to it, a bowl of ramen and a katsudon — freshly cooked eggs and pork cutlet – fall fresh out of the pan. Plates are stacked high with colorful sashimi and elaborate parfaits. It’s a feast for the eyes — and the eyes alone.

These are “shokuhin sampuru” — the highly realistic food replicas commonly displayed in front of restaurants in Japan, intended to lure customers inside. A familiar sight in Japan, a vast array of these replicas are now on display in London in an exhibition that is the first of its kind, according to Simon Wright, the show’s curator and director of programming at Japan House London.

“Looks Delicious!” features replicas made by the Iwasaki Group, the first company dedicated to the production of these fake foods which remains today the largest producer in Japan. (The company needs to make on average one replica every 40 minutes in order to keep the business viable, according to Wright.) Its founder, Takizo Iwasaki, was reportedly inspired to create wax models of food from a childhood memory of seeing candlewax fall into a puddle and form into the shape of a flower.

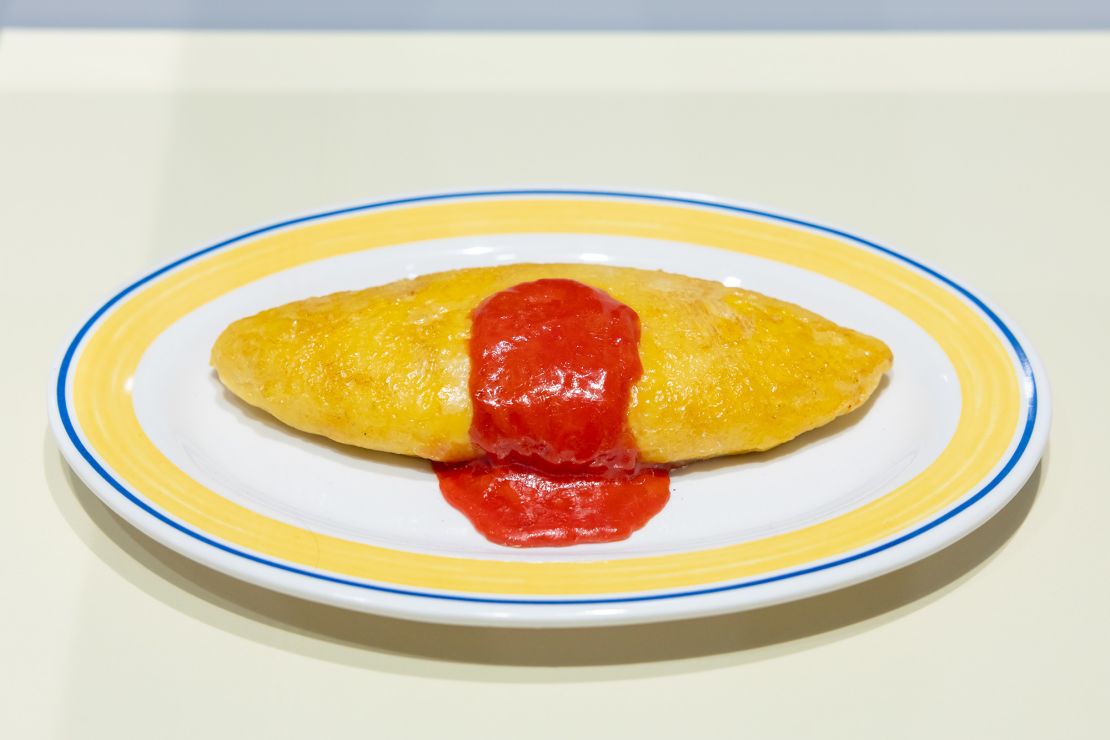

A version of Iwasaki’s first ever replica — modeled after an omelette his wife made — is on display at the exhibition, named “kinen omu,” or celebration omelette. Over time, Iwasaki developed a production method using wax and agar jelly molds, though now the company mainly uses PVC.

However the origin story of food replicas more broadly is a “mess,” according to Nathan Hopson, a professor of Japanese at the University of Bergen who has studied the subject in-depth. Hopson told CNN in a video call that there are a myriad of theories as to how the replicas came to be introduced in Japanese culture.

One popular explanation, according to Japan House, is that they were made to familiarize Western dishes to a “curious yet cautious” Japanese public who otherwise wouldn’t know what to expect if they made an order. Among the swaths of traditional Japanese food, the exhibit also features strikingly realistic renderings of bacon, eggs and grilled cheese.

The exhibition’s centerpiece is a map of Japan made up of food replicas representing each of the country’s 47 prefectures. Each replica was specially commissioned and made by the Iwasaki Group, which created replicas of some dishes for the very first time.

It wasn’t easy to choose just one dish per prefecture for Wright’s team, who started by consulting a list created by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, before also reaching out to people from the regions. “You start to discover that a lot of people have a lot of opinions on this,” Wright said.

An exception was made for the northernmost prefecture of Hokkaido, the only one represented by two dishes: “kaisen-don,” a bowl of rice topped with seafood, and “ohaw,” a soup from the indigenous Ainu community. The Iwasaki Group had never made a replica of ohaw before, so the exhibition’s team had to ask the community to make them the dish, which was sent to Osaka overnight, photographed, and made into a replica the next day.

Creating the impression of realistic liquids is one of the most difficult techniques to master in replica-making. Done right, the result is bowls of soup and glasses of wine which give the sense that they would spill over the table if mishandled by a curious visitor.

There is a ‘hyper-realism’ to these foods, explained Wright, which is intended to trigger the prospective customer’s memory, imagination — and hopefully catch their eye. “They are there to attract people in an instant,” he said. “To try and lure them to have lunch or to have dinner there.”

And importantly, people trust that the food they see on display will live up to the food they get in real life, with Hopson calling them a “promise.” “I can go into any place in Japan, in any town and city and know exactly what I’m going to get,” he said.

But the replicas are more than marketing made pleasing to the eye. They serve a practical function, dating back to when they were introduced by Shirokiya, a major department store, in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake on Japan’s main island in 1923.

The store was one of the first places to open in Tokyo after the earthquake and serviced the masses of people who could no longer cook for themselves at home, explained Hopson, who studied the company’s history. Rather than decide their order when they reached the store’s top-floor cafeteria, a new system was designed: window displays could give customers the opportunity to look at the food on offer while they waited in line.

“It’s really about this management side, supply-side rationalization that’s very much part of creating a new, modern, capitalist success story,” said Hopson, who added that they really took off in the 1970s, or Japan’s ‘year-zero’ for fast food.

Though they continue to be a common sight in Japan’s restaurant windows, the replicas are also evolving in their function. The exhibition shows how food replicas can be used for quality control in agriculture, food manufacturing and for nutritional purposes by displaying the ideal diet for a person with diabetes.

The exhibition also gives visitors a chance to arrange their own bento box with the replica treats. Who said you shouldn’t play with your food?

“Looks Delicious!” runs until February 15. See more images from the exhibition below.