During much of the 1980s, Justice Sandra O’Connor, the first woman on the Supreme Court, cast a consistent vote against abortion rights.

But in 1989, things changed. A new conservative majority was in place and appeared to have the votes to eviscerate Roe v. Wade, for the first time since the 1973 landmark made abortion legal nationwide.

O’Connor struggled with the new dynamic. Some of her ambivalence emerged in her opinions, but newly available correspondence and handwritten notes of secret deliberations reviewed by CNN flesh out her budding resistance. They show her evolution in a Missouri abortion case, as she faced pressure to cast the decisive vote that would have reversed Roe and instead set a path that preserved abortion rights for another three decades.

The O’Connor archive demonstrates how the nine Supreme Court justices, both then and now, negotiate behind the scenes through memos, personal entreaties, and various means of persuasion — some more successful than others. At times, the papers show, pressure on individual justices can have the opposite of the intended effect.

The documents also underscore the difference on abortion rights between the court of that era and the contemporary far-right bench, which in 2022 jettisoned Roe and nearly a half century of reproductive rights.

Pressing for reversal of Roe and pushing hard on O’Connor were Justice Antonin Scalia, relatively new to the bench but already known for a forceful, if sometimes bullying, presence; and Chief Justice William Rehnquist, one of the original two dissenters in Roe.

After a closed-door vote of the nine justices, Rehnquist took the lead for what he thought would be a five-justice majority opinion reversing Roe’s legal framework. The Missouri case — Webster v. Reproductive Health Services — had been heard late in the court’s term, so Rehnquist was trying to accomplish this in two months — an extraordinarily fast turnaround for any case, let alone one of such magnitude.

“Because of the ‘media-hype’ that this case has received, and because we are cutting back on previous doctrine in this area, I think it more than usually desirable to have an opinion of the Court if we possibly can,” Rehnquist wrote in a private note to his four fellow conservatives, including O’Connor, asking them for quick feedback on his draft.

Among the provisions of the Missouri statute was a ban on the use of public facilities for abortion services and a requirement that physicians test for the viability of a fetus believed to be more than 20 weeks old. The provision challenged Roe’s limit on regulation of abortion through the second trimester of pregnancy, about 24 weeks. State officials and their many anti-abortion backers, including the George H.W. Bush administration, wanted the court to use the case to overturn Roe.

O’Connor, the first appointee of Reagan, bristled at the chief’s deadline and seemed to recognize immediately his goal and the pressure underway. She told Rehnquist outright that despite his “disclaimer,” the rationales adopted in his draft “effectively overrule Roe.”

The O’Connor documents opened this year at the Library of Congress reveal that as the arm-twisting of Rehnquist and Scalia faltered, the subtler persuasion of Justice John Paul Stevens, a 1975 appointee of Gerald Ford who moved left, became more effective.

The correspondence and notes foreshadow where O’Connor landed in the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey case, when Justice Anthony Kennedy, hostile to Roe v. Wade in 1989, was ready to join O’Connor in upholding Roe. That decision secured Roe’s place in American life until it was overturned by a 5-4 conservative majority in the 2022 Dobbs case.

O’Connor retired in January 2006 and was succeeded by Samuel Alito, who wrote the Dobbs opinion.

Tensions rise between O’Connor and Scalia

Justices’ papers, made available only after members of the court have died, can reveal up-close the evolution of a decision. Not all justices arrange to make their papers available, however, and those of O’Connor, who died last December, are the first opened from any justice on the conservative side of the Missouri case. (The archives of the four liberals were already open.)

O’Connor’s personal notes demonstrate that she began the deliberations highly critical of Roe, referring to it as “fundamentally wrong.” (That decision had declared a constitutional right to end a pregnancy, rooted in the 14th Amendment’s due process guarantee of personal liberty.)

O’Connor, appointed in 1981, took particular issue with Roe’s trimester framework tied to the viability of a fetus, that is, when it could live outside the woman. Under Roe, in the first trimester of pregnancy (roughly the first three months), an abortion decision was left to a woman and her physician; in the second trimester, a state could limit access to the procedure in ways reasonably related to a woman’s health; in the third trimester, after fetal viability, a state could promote its “interest in potential life” and ban abortion except when necessary for the woman’s life or health.

O’Connor wrote in a 1983 case from Ohio that, as medical advances moved the point of viability up earlier in a pregnancy, the trimester approach was “clearly on a collision course with itself.” She reiterated her criticism of Roe in 1986 when she dissented in a Pennsylvania dispute, writing, “The State has compelling interests in ensuring maternal health and in protecting potential human life, and these interests exist throughout pregnancy.”

By the time of the 1989 Webster v. Reproductive Health Services case, however, two additional Reagan appointees had joined the bench (Scalia and Kennedy), and they appeared poised to help create a new majority to overturn Roe.

Rehnquist, whom O’Connor had known since they were students at Stanford Law School and then working and raising families in Phoenix, had joined the court in 1972. Far more conservative than the other justices at the time and dubbed “Lone Ranger” by law clerks, Rehnquist by 1986, when elevated by Reagan to chief justice, was more apt to negotiate — or at least to avoid offending colleagues.

Scalia, a devout Catholic and father of nine known as “Nino,” shared Rehnquist’s opposition to Roe. But he arrived in 1986 with an even brasher approach to challenging the existing order. Wielding a lively wit and sharp pen, he eschewed the niceties as he reviewed his colleagues’ drafts, objecting to legal reasoning and sparring over punctuation. He became known for his “Ninograms.”

Scalia and O’Connor, with her cautious conservatism, naturally clashed.

Accelerating the tensions all around was the time pressure of the Missouri case. It was heard in late April, and the justices were trying to resolve it on their usual timetable for finalizing decisions by the end of June.

Justices show their cards in private meeting

According to O’Connor’s personal notes from a private conference session after the court’s oral arguments, she criticized Roe but also said she believed the Missouri provisions at issue could be upheld without overruling the precedent.

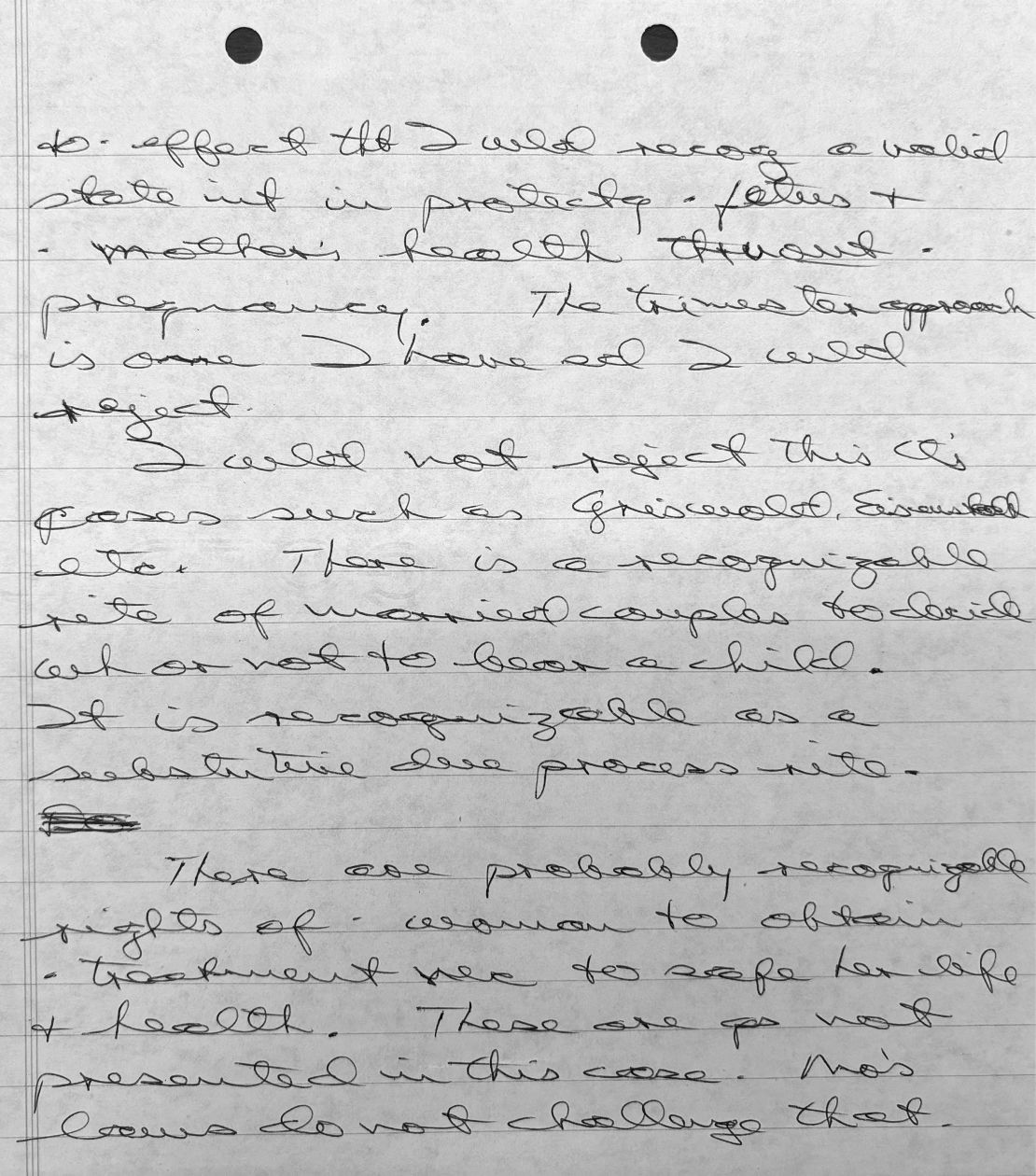

Still, her notes suggest she believed at the time that the court might not be bound by its usual adherence to precedent and might find that Roe was “fundamentally wrong.” She jotted in her notes that she had previously been on record “to effect that I would recognize a valid state int(erest) in protecting fetus and mother health throughout pregnancy.”

O’Connor also personally recorded the sentiment of fellow conservatives ready to side with Missouri and the four liberals who would dissent.

Kennedy, relatively new to the bench as Reagan’s 1988 appointee, declared his opposition to Roe. O’Connor wrote that Kennedy said, “Roe is just flawed analytically” and that he wanted to “return this debate to democratic process” in the states.

Scalia told his colleagues, according to O’Connor’s notes, that litigation arising from Roe “hurts public perception of (the Court) and affects all we do.” Justice Byron White, who, like Rehnquist, had dissented in Roe, was the fifth justice in the majority in the Missouri case.

Chief justice circulates draft to gut Roe

Oral arguments were heard on April 26, 1989, and the justices met in private two days later. With a majority siding with Missouri and disapproving of Roe, to varying degrees, Rehnquist began crafting an opinion that would discard the trimester framework, along with fetal viability as a standard for constitutionally permissible regulation.

Rehnquist was ready to send around a draft on May 18, but first the chief justice wanted to keep his opinion only among those on his side.

In a private note that day, he wrote, “Dear Byron, Sandra, Nino and Tony … Attached is a rough draft of a proposed opinion of the Court in this case.” He urged them to respond within a matter of days, so he could meet an internal June 1 deadline for circulating first drafts of majority opinions in all cases.

White responded to Rehnquist on May 22: “I can go along with your draft in this case if the others on our side do so.”

On the same day, Kennedy told Rehnquist: “I am in substantial agreement with your excellent opinion in this case. As you know, in my view the case does provide a fair opportunity to assess the continuing validity of Roe v. Wade, and I would have used the occasion to overrule that case and return this difficult issue to the political systems of the states.”

Even though Rehnquist was undercutting the fundamentals of Roe, he was not explicitly overruling it.

O’Connor, however, saw the draft for what it was.

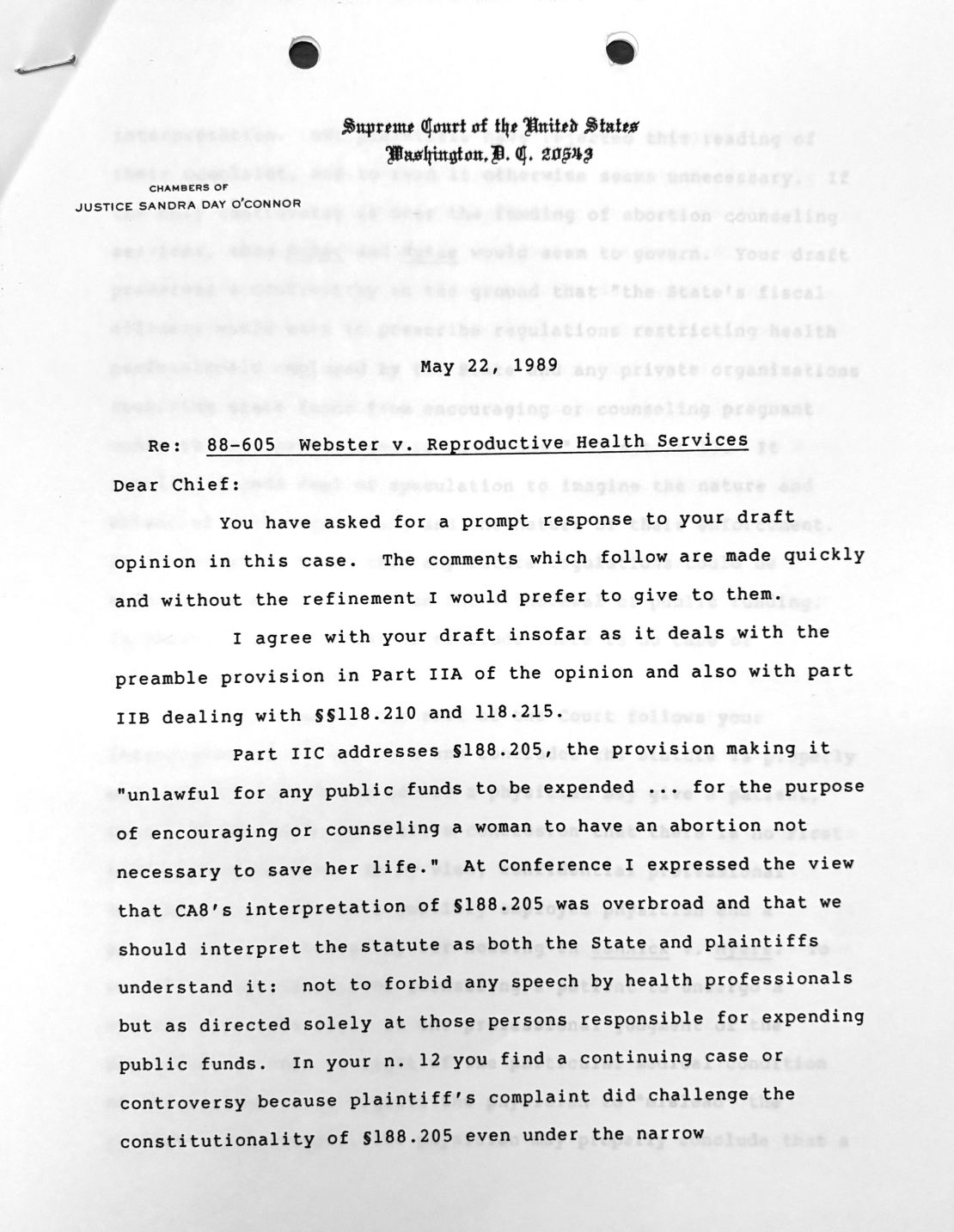

She opened her May 22 memo to him, first, with a reference to his effort to jam the draft through: “You have asked for a prompt response to your draft opinion in this case. The comments which follow are made quickly and without the refinement I would prefer to give to them.”

Then she got to the heart of the matter. She said the Missouri statute should be upheld, but the court should go no further. “Your draft goes on to reexamine the Roe framework and to reject the trimester framework. It also rejects the point of viability as constitutionally relevant,” she wrote. “Those two holdings effectively overrule Roe despite the disclaimer.”

O’Connor acknowledged her past criticism of Roe but said Rehnquist was taking it too far in this case.

“I have previously indicated that I would reject the trimester framework, and would recognize the State’s interest in potential life at all stages of the pregnancy,” she told him but added, “I see no necessity to go further than that in this case and hold that the point of viability has no relevance at all.”

Scalia says O’Connor’s objection is ‘irrational’

The next day, Scalia addressed O’Connor’s vacillation in a way that likely continued to rub her the wrong way.

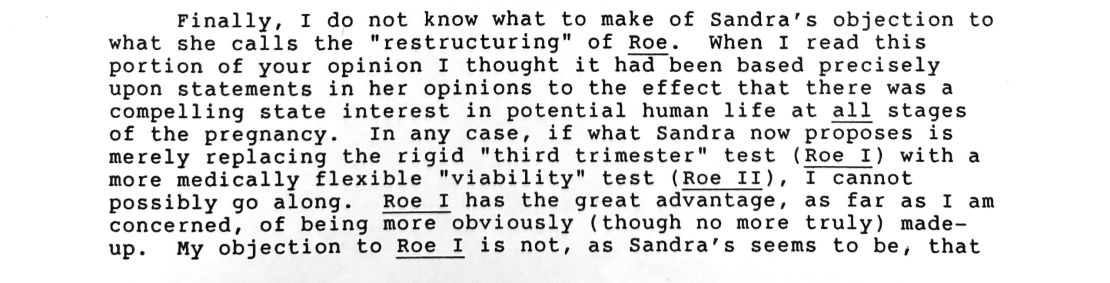

“I do not know what to make of Sandra’s objection to what she calls the ‘restructuring’ of Roe,” Scalia wrote to Rehnquist, with copies of the memo sent to the others in their group. “When I read this portion of your opinion I thought it had been based precisely upon statements in her opinions to the effect that there was a compelling state interest in potential human life at all stages of the pregnancy.”

“In any case, if what Sandra now proposed is merely replacing the rigid ‘third trimester’ test (Roe I) with a more medically flexible ‘viability’ test (Roe II), I cannot go along. Roe I has the great advantage, as far as I’m concerned, of being more obviously (though no more truly) made-up.”

Within a few weeks, as he drafted his own opinion, Scalia would deem O’Connor’s approach “irrational” and say it “cannot be taken seriously.” But in this first private exchange with his colleagues in May, he explained that his objection was that Roe lacked constitutional legitimacy “since it is based neither upon constitutional text, nor upon plausible constitutional theory, nor upon societal tradition.”

“Until that error is corrected – until we make clear that it is not our job generally to decree what is ‘sensible’ – the public perception of this Court as an institution will continue to be grotesquely distorted as we have seen in the past year,” Scalia wrote in his May 23 note, bemoaning that his colleagues might be unable to “muster sufficient resolve to overrule (Roe), rather than heap error upon error with Roe II.”

Two days later, on May 25, when Rehnquist sent his draft to the full court, his tactics provoked a sharp response from the liberal dissenters.

“As you know, I am not in favor of overruling Roe v. Wade,” Stevens wrote, “but if the deed is to be done I would rather see the Court give the case a decent burial instead of tossing it out the window of a fast-moving caboose.”

Likely sharing some of that latter sentiment, O’Connor in the end stripped Rehnquist of a court majority for the “deed.” Rehnquist was left with a plurality (just four justices) for his full opinion. For a decision to become national precedent and bind lower courts, a majority (at least five justices) is needed.

Negotiations went beyond the usual late-June deadline. When all the opinions were released on July 3, 1989, O’Connor had joined Rehnquist in upholding the Missouri law, writing in a concurring statement, “It is clear to me that requiring the performance of examinations and tests useful to determining whether a fetus is viable, when viability is possible, and when it would not be medically imprudent to do so, does not impose an undue burden on a woman’s abortion decision.”

But she separated herself from the chief justice and the others on the right wing by leaving Roe v. Wade intact. She said reconsideration of the 1973 milestone would conflict with the “fundamental rule of judicial restraint.”

“When the constitutional invalidity of a State’s abortion statute actually turns upon the constitutional validity of Roe,” she wrote in her concurrence, “there will be time enough to reexamine Roe, and to do so carefully.”

In a separate opinion of his own, Scalia made clear his annoyance that O’Connor had withheld her crucial fifth vote and why. He wrote that, “Justice O’Connor’s assertion, that a ‘fundamental rule of judicial restraint’ requires us to avoid reconsidering Roe, cannot be taken seriously.”

The aftermath: A liberal reaches out and Roe lasts for decades

The correspondence among O’Connor, Rehnquist and Scalia in the Missouri case emerged only this year. It adds to the understanding of a private note from Stevens sent to O’Connor made public in his Webster files in 2023.

Across a range of cases, Stevens’ once-private papers revealed his delicate negotiations with O’Connor through the years, trying to meet her part way as she inched left. The Chicago native Stevens and ranch-born O’Connor had their differences, but they shared a personal code of courtesy.

Four days before the 1989 abortion case came down, Stevens sent O’Connor a note that she saved in her own files: “At Conference,” Stevens wrote, “I said I was going to add a paragraph to my opinion in Webster, but after further reflection decided not to do so. For your information only, however, I enclose the paragraph that I had drafted. Have a good summer. Respectfully, John.”

His paragraph, intended for her eyes only, said: “’Judicial restraint’ is a concept that judges universally endorse. Different judges define the concept in different ways, but the giants who sat on this Court consistently sought to avoid the unnecessary or premature adjudication of constitutional questions. … Although I disagree with Justice O’Connor’s views on the merits of the issues discussed in my opinion, I wholeheartedly endorse her wise decision to adhere to the best traditions of this Court in its constitutional adjudication.”

The next year, O’Connor moved another step away from Scalia and Rehnquist as she for the first time voted to strike down an abortion restriction. A disputed Minnesota law had required notification of both parents before a teenager could have an abortion.

O’Connor’s vote in the case gave liberals the majority, and Stevens wrote the decision for the 5-4 court. Senior liberal Justice William Brennan penned a private note to his colleagues on the left saying it was important that all the liberals sign on to “as much of John’s opinion as we possibly can, especially now that Sandra has agreed to invalidate at least part of an abortion law.”

Two years after the 1990 Minnesota case, O’Connor, joined by Kennedy and Justice David Souter, a George H.W. Bush appointee, wrote an important opinion upholding abortion rights in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

They reaffirmed Roe but discarded the trimester approach and said the test for a valid regulation was whether it would put an “undue burden” on a woman seeking an abortion.

“Some of us as individuals find abortion offensive to our most basic principles of morality, but that cannot control our decision,” the trio wrote in 1992. “Our obligation is to define the liberty of all, not to mandate our own moral code.”

That decision survived for three decades, until the Dobbs majority reversed all abortion rights and declared, “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start.”