Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

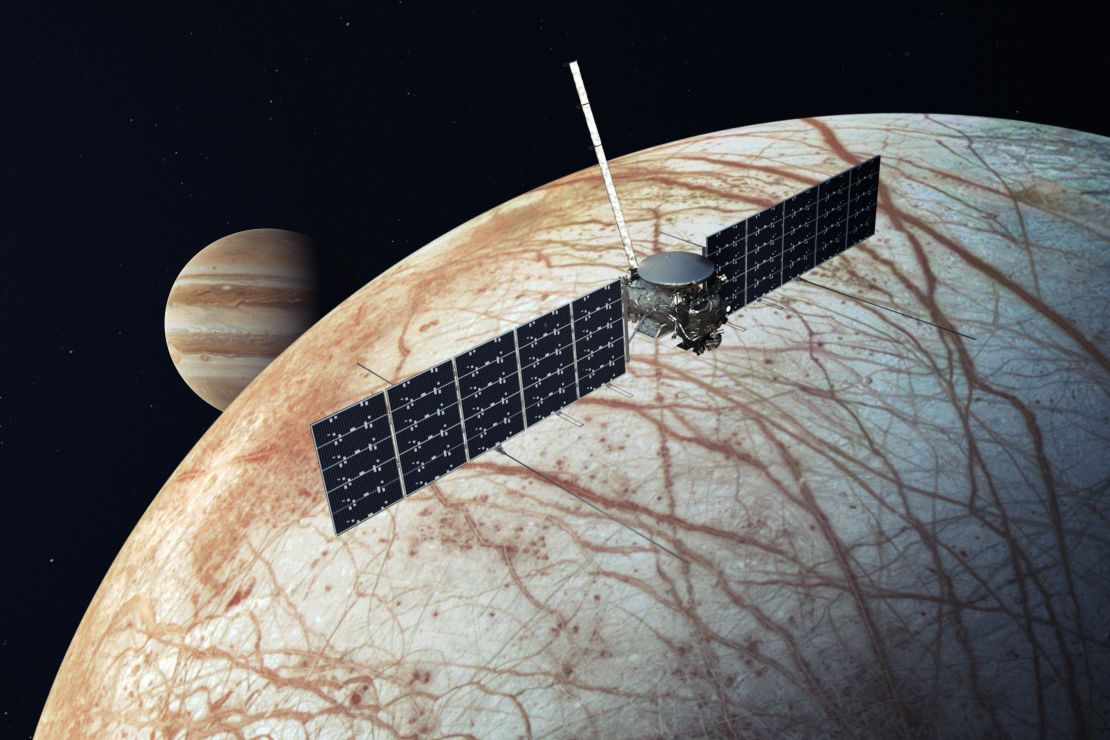

The Europa Clipper spacecraft passed a key milestone on Monday and is on track to launch next month to explore and seek signs of habitability on one of Jupiter’s moons, according to NASA. The launch window for its journey opens on October 10.

The mission passed Key Decision Point E, a critical planning stage approving the mission to move forward with launch. The approval was a relief to the Europa Clipper team after the discovery in May of a possible issue with transistors on the spacecraft.

Transistors help control the vehicle’s flow of electricity, and engineers were concerned about the components’ survival in Jupiter’s harsh radiation environment.

Extensive testing of the transistors took place over four months at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California; Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland; and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The team was able to complete necessary testing in time, preventing a 13-month delay of the launch to explore Europa, an ice-covered world that may have the potential to support life in its salty, subsurface ocean. Europa Clipper carries 10 science instruments that could determine whether life is possible on another place in our solar system besides Earth.

Now, Europa Clipper has been approved to launch, with no changes to the mission plan, goals or trajectory.

“It’s the last sort of big review before we really get into that launch fever, and we’re really happy to say that they unequivocally passed that review today,” said Nicola Fox, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, during a news conference Monday.

Solving the radiation problem

In May, the manufacturer of the transistors alerted the mission team that the parts may not be as radiation-resistant as previously believed. The transistors are located across the spacecraft.

Jupiter dwarfs other worlds as the largest planet in our solar system, and it has a magnetic field 20,000 times stronger than Earth’s. That magnetic field traps charged particles and accelerates them to high speeds. The rapidly moving particles release energy in the form of intense radiation that bombards Europa and Jupiter’s other closest moons.

Any spacecraft heading to Jupiter needs radiation-hardened electronics.

“Jupiter’s engulfed in more radiation than any planet in our solar system, and that’s one of the reasons why exploring the Jupiter system is so challenging,” said Jordan Evans, Europa Clipper project manager at JPL.

“Europa sits near the outer edge of the worst part of that radiation belt,” he added. “Flying near Europa exposes us to this high flux of damaging particles, and so the mission engineers and Europa Clipper need to be sure that the spacecraft components can survive that radiation environment for the duration of our four-year mission.”

Data from previous NASA missions to Jupiter, including the Juno probe currently studying the planet and some of its moons, was used to validate the testing process for the transistors, Evans said.

The tests were conducted 24 hours a day since May, and they simulated spaceflight conditions to see how the spacecraft and its components would fare when the vehicle conducts 49 flybys of Europa and ultimately 80 orbits around Jupiter over a four-year period.

The team determined that the transistors can self-heal in between flybys.

“We concluded, after all of this testing, that during our orbits around Jupiter, while Europa Clipper does dip into the radiation environment, once it comes out, it comes out long enough to give those transistors the opportunity to heal and partially recover between flybys,” Evans said.

A radiation monitor on the spacecraft will enable the team to check how the transistors are faring.

“I personally have high confidence that we can complete the original mission for exploring Europa as planned,” Evans said.

Exploring an ocean world

When Curt Niebur, Europa Clipper program scientist, began working at NASA in 2003, he faced the task of pushing a Europa mission forward. Each year, the effort to get Europa Clipper designed and built has seemed more difficult, he said.

“There was no harder year than this past year and especially this past summer,” Niebur said. “But through all of that, the one thing that we never doubted was that this was going to be worth it. It’s a chance for us to explore, not a world that might have been habitable billions of years ago, but a world that might be habitable today — a chance to do the first exploration of this new kind of world that we’ve discovered very recently called an ocean world that is just totally immersed and covered in a liquid water ocean completely unlike anything we’ve seen before. That’s what’s waiting us at Europa.”

Europa Clipper is not a life-detection mission, Niebur added.

The mission’s key goals are centered on figuring out whether the proper ingredients to support life as we know it — including water, energy and chemistry — are on Europa. And without any scientific instrument that can directly determine the existence of life, Clipper can’t conclusively find evidence of it, he said.

“You can bet your bottom dollar that if Europa Clipper tells us, yes, those ingredients are there, that we are going to be knocking on the door fighting for second mission to go looking for life,” Niebur said.

Europa Clipper will be key to helping NASA determine where to send follow-up missions, such as parts of the ice crust that may be thin and where water from the subsurface ocean could gush, said Laurie Leshin, director for JPL.

“If we get there and we do this investigation, and the good news is it has all the ingredients and it is habitable, what that means is that there are two places in one solar system that have all the ingredients for life that are habitable right now at the same time,” Niebur said.

“Think of what that means when you extend that result to the billions and billions of other solar systems in this galaxy,” he added. “Setting aside the ‘Is there life’ question on Europa, just the habitability question in and of itself opens up a huge new paradigm for searching for life in the galaxy.”