Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

In H.G. Wells’ 1897 science fiction novel, “The Invisible Man,” the protagonist invents a serum that makes the cells in his body transparent by controlling how they bend light.

More than 100 years later, scientists have discovered a real-life version of the substance: A commonly used food coloring found in snack foods and candies such as tortilla chips and candy corn can make the skin of a mouse temporarily transparent, allowing scientists to see its organs function, according to a new study published Thursday in the journal Science.

The breakthrough could revolutionize biomedical research and, should it be successfully tested in humans, have wide-ranging applications in medicine and health care, such as making veins more visible to draw blood.

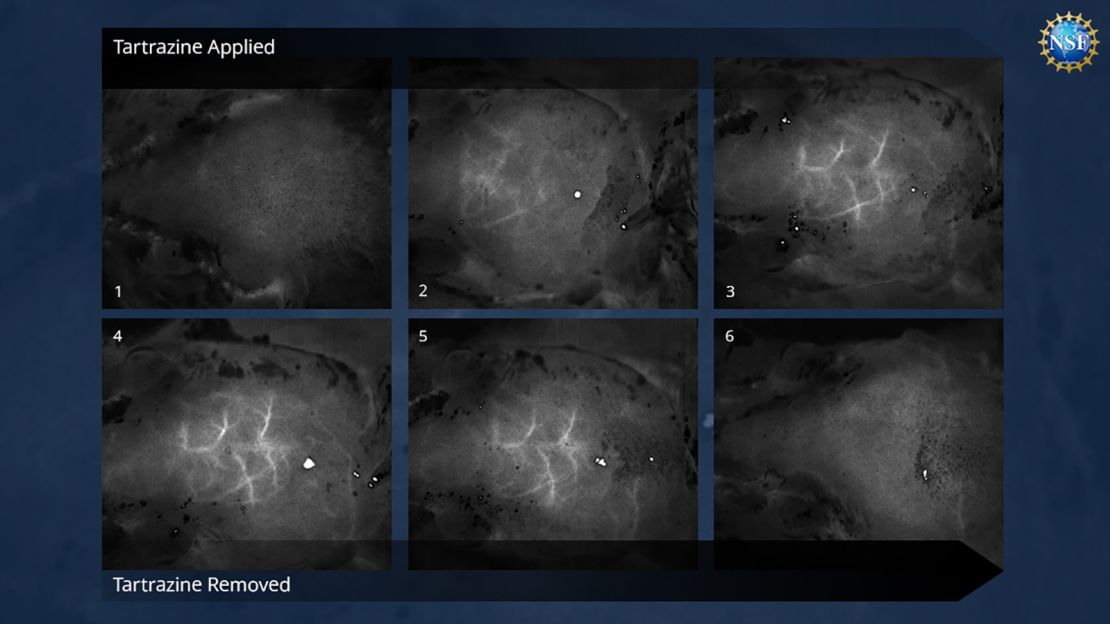

Researchers made the skin on the skulls and bellies of live mice transparent by applying a mixture of water and a yellow food coloring called tartrazine. Washing away any remaining solution reversed the process, which did not harm the animals. The mice’s fur was removed before the application of the solution.

“For those who understand the fundamental physics behind this, it makes sense; but if you aren’t familiar with it, it looks like a magic trick,” said the study’s first author, Zihao Ou, assistant professor of physics at the University of Texas at Dallas, in a statement.

Light-absorbing dye molecules

The “magic” uses insights from the field of optics. Light-absorbing dye molecules enhance the transmission of light through the skin by suppressing the tissue’s ability to scatter light.

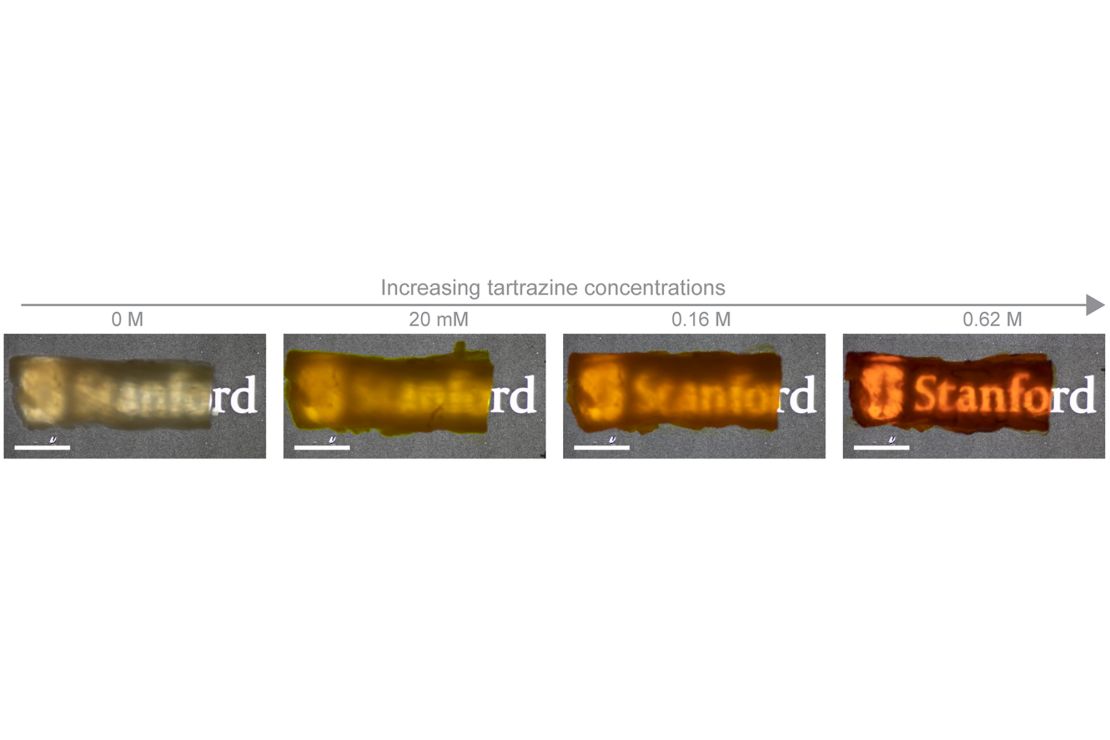

The dye, when mixed with water, modifies the refractive index — a measure of the way a substance bends light — of the aqueous part of the tissue to better match the index of proteins and fats in the tissue. The process is akin to a dissipating cloud of fog.

“We combined the yellow dye, which is a molecule that absorbs most light, especially blue and ultraviolet light, with skin, which is a scattering medium,” said Ou, who conducted the study as a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University in California.

“Individually, these two things block most light from getting through them,” he said. “But when we put them together, we were able to achieve transparency of the mouse skin.”

Once the dye had completely diffused into the skin, the skin became transparent.

“It takes a few minutes for the transparency to appear,” Ou said. “It’s similar to the way a facial cream or mask works: The time needed depends on how fast the molecules diffuse into the skin.”

The team experimented with chicken breasts before conducting work on live animals.

In mice, the researchers were able to observe blood vessels directly in the surface of the brain through the transparent skin of the skull. The mice’s internal organs were visible in the abdomen as well as the muscle contractions that move food through the digestive tract.

The transparent areas take on an orangish color, Ou said, similar to that of the food dye.

The dye used in the solution is commonly known as FD&C Yellow No. 5, certified for use by the US Food and Drug Administration. The synthetic dye is frequently used in orange- or yellow-colored snack chips, candy coating, ice cream and baked goods. However, a 2021 study by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment linked the coloring with behavioral difficulties and decreased attention among children. A state bill, if signed into law, would ban the use of the food coloring in food served in public schools in California.

Ou said it was important that the dye is biocompatible — safe for living organisms. “In addition, it’s very inexpensive and efficient; we don’t need very much of it to work,” he said.

Possible biomedical applications for humans

The researchers have not tested the process on humans, and it’s not clear what dosage of dye or delivery method would be necessary. Human skin is about 10 times thicker than that of a mouse, according to the researchers.

“Looking forward, this technology could make veins more visible, easing … the procedure of drawing blood or administering fluids via a needle — especially for elderly patients with veins that are difficult to locate,” said senior author Guosong Hong, a Stanford assistant professor of materials science, via email.

“Moreover, this innovation could assist in the early detection of skin cancer, improve light penetration for deep tissue treatments like photodynamic and photothermal therapies, and make laser-based tattoo removal more straightforward.”

Christopher Rowlands, a senior lecturer in the department of bioengineering at Imperial College London, said he was “kicking himself” for not coming up with the same insight as the Stanford-led team, which is based on the widely studied and long-standing physics principle called Kramers-Kronig relations: When a material absorbs a lot of light at one color, it will bend light more at other colors.

“It’s blatantly obvious when someone points it out, but no one had thought of it for 100 and something years,” said Rowlands, who wasn’t involved in the study but coauthored a commentary published alongside the research.

Along with Jon Gorecki, an experimental optical physicist at the same institution who also wasn’t involved in the study, Rowlands wrote that the approach offered a new way to visualize the structure and activity of deep tissues and organs in a living animal in a safe, temporary and noninvasive manner.

“It just works. You rub it on a mouse, and you can see what it had for breakfast. It’s that powerful,” he added.

Rowlands and Gorecki said that existing methods to turn tissue transparent use solutions that have side effects such as dehydration and swelling and can alter the structure of the tissue. However, tartrazine was used at a low concentration, and its effects were easily undone, potentially facilitating prolonged study of biological processes in live animals, they wrote.

The duo noted the discovery was an example of life imitating art, with the dye solution echoing the serum imagined in “The Invisible Man.”

“The protagonist (in the story) invents a serum that renders the cells in his body transparent by precisely controlling their refractive index to match that of the surrounding medium, air,” they wrote.

“One hundred twenty-seven years later … biocompatible dyes make living tissues transparent by tuning the refractive index of the surrounding medium to match that of the cells.”

However, Ou and Hong said a totally invisible mouse was a stretch: The current approach cannot render bone transparent.

“So far, we only tested soft tissues, including brain, muscle, and skin. We haven’t done much investigation with hard tissues such as bone, so I am not sure if we would be able to make the mouse completely invisible,” Ou said via email.

“However, a partially transparent (mouse) will already enable numerous research opportunities to answer questions relating to development, regeneration, as well as aging.”