When I visited Rocklin Elementary school, I sat in on a lesson with a third-grade class – a lesson I would never have imagined as a father, a journalist or a trauma surgeon.

“Chances are, you’re never ever going to have to use this. If you do, it’s gonna be scary,” Kate Carleton told the 20 or so 8- and 9-year-olds. “But because we’ve taught you what to do, it makes it a little less scary.”

She spent the next 30 minutes teaching them how to stop a wound from bleeding out. The lesson is appropriately titled “Stop the Bleed.”

Carleton is a trauma nurse at Sutter Roseville Medical Center, a level 2 trauma center in Rocklin, California, a northern suburb of Sacramento. At the beginning of her 17-year career, she saw a lot of car crashes, motorcycle accidents and falls. More recently, the number of gunshot wounds coming through her hospital has increased, most often from domestic violence or suicide.

On this day, she was kneeling on the ground to show these little kids the techniques paramedics often use in the field to stop bleeding. And as I looked around the classroom, I could tell that the kids were really listening.

“Now, if you’ve got that bleeding to stop on that person, what did you do for their life?” she asked the kids.

Hands flew up.

“You saved their life,” answered one little girl.

Born out of tragedy

A little more than seven years ago, Carleton was watching a special about the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, and like so many parents, she wondered about her own children, then in kindergarten and second grade. Was there anything she could do to make a difference and help keep them safer in a moment like that?

Carleton approached her daughter’s kindergarten teacher and asked whether it was possible to create a curriculum to teach them how to handle these injuries. She wasn’t sure what the response would be because after all, these were young children.

But as the number of mass shootings continued to grow, so did the realization that anyone could suddenly become a first responder — even a child. The proposal was approved, and since then, she has been teaching classes to students throughout the Rocklin school district on the basics of bleeding control.

Carleton is part of a larger movement also known as “Stop the Bleed,” a campaign that was born out of the tragedy at Sandy Hook. Hartford Hospital trauma surgeon Dr. Lenworth Jacobs was tasked with reviewing the autopsies of the 20 children and six adults killed that day, to find any lessons that could be learned out of the horror.

“You cannot imagine what the kinetic energy of an AR-15 does, or a bullet does, to a 6-year-old,” Jacobs said. “This is not civilized.”

School shootings are rare, but gunshot injuries are not

Although a child dying at school in a mass shooting may be unlikely, a child dying from a gunshot is not. Firearms are the leading cause of death among people 18 and younger in the US, accounting for nearly 19% of all childhood deaths.

The most recent data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that both the rate and the number of children dying from gunshot wounds are the highest they have been since 1999, when data on children’s mortality and firearms was first collected. And although firearm mortality in the adult population is most often from suicide, for children, homicide is driving the deaths.

After poring over the autopsies, Jacobs gathered trauma specialists from across the country and developed “a protocol for national policy to enhance survivability from active shooter and intentional mass casualty events,” known as the Hartford Consensus. The nearly 100-page document included a letter from then-Vice President Joe Biden, who said the report was a “call to action.”

“With very little training and equipment, the individuals closest to the scene of an accident or mass casualty situation can control bleeding until first responders arrive to take over treatment,” Biden wrote.

Much of the Hartford Consensus was adopted from lessons learned in combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. In the military, it’s known as “buddy aid”: the practice of fellow troops being trained in first aid to help wounded colleagues on the battlefield. The practices are basic, but stopping bleeding, using a tourniquet and putting these steps into practice before a wounded soldier reaches the hospital greatly improves their chances of survival. Those troops who had tourniquets applied before their bodies went into shock had a survival rate of 96%, compared with just 4% of those who got a tourniquet after blood loss caused them to go into shock.

A driving tenet of the Hartford Consensus was time. “Pretty much all of these (mass casualty) events are over in 15 minutes, and it takes more than that to get the system to respond to you,” Jacobs explained.

Experts say that the average response time for an ambulance in urban areas in the US is about eight minutes — more time than it takes for a person to bleed out from a gunshot wound.

Turning bystanders into first responders

To give a person the best chance at survival after being shot, the priority is simple. “Stop the bleeding. Keep the blood inside the body,” Jacobs said. The most efficient and quickest way to do that: turn bystanders into immediate responders by teaching them to pack a wound and use a tourniquet.

Eleven years after Jacobs and other experts first met to discuss what would ultimately become the Hartford Consensus, more than 3 million people worldwide have learned the basic principles of “Stop the Bleed” through a certification program developed by the American College of Surgeons and the American Red Cross.

According to the ACS, bleeding control kits containing gauze and tourniquets are now required in schools in at least 10 states, and teachers and staff are required to be trained in at least three states. Two states require schools to offer Stop the Bleed training to students: in Arkansas for students in ninth grade and above and in Texas for those in seventh grade and above.

After 19 fourth-graders and two teachers were killed at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, in 2022, a state representative introduced a bill proposing to lower the minimum grade for Stop the Bleed training to third grade. The bill never made it out of committee because of pushback.

Carleton says she’s not surprised. “Why it got started is frightening,” she tells me, “but I do think there’s a way to teach the information where it’s not.”

Meeting kids where they’re at

When Carleton speaks to the kids, she doesn’t mention guns or violence at all. During the class I visited, she asked the kids how many of their parents use power tools or could be hurt working around the house.

“If I’m working in the kitchen and I’m cutting vegetables, can I get cut? Can that cause me to bleed?” she asked the students.

She uses language that kids can easily grasp: “Look for when blood puddles or when it rains like a sprinkler. The first step, take any cloth you can find and stuff a corner of it into the wound as deep as you can.” She was teaching them the basic principles of packing a wound. On the day I was there, she told the kids they could use anything to pack a wound, even a “dirty, smelly sock.”

“Stopping the bleeding was most important, and they could give antibiotics later in the hospital to prevent infections,” she said. “Do whatever you can to just stop the bleed.”

It’s the same kind of approach that pediatric trauma nurse Missy Anderson takes when she teaches Scout troops and children’s groups in Denver. Anderson is the pediatric trauma program manager at Denver Health and describes the tourniquets as “magical bracelets” — a concept that most kids can immediately understand.

Carleton stopped bringing up gun violence after a handful of parents complained, but she doesn’t shy away when someone raises it. In a sixth-grade class I visited, a student asked, if someone was shot in multiple places, where should they try to stop the bleed?

Carleton answered quickly, “Where they are bleeding the most.”

“I try to acknowledge the kids on where they’re at,” she told me. “I acknowledge it and we move on so that we can continue to talk about how to get the bleeding to stop.”

But the topic of gun violence gives her pause. “It tugs at my heartstrings a little bit, for sure,” she said.

Like Carleton, Anderson keeps the focus on safety, not violence.

“What if no guns existed in the whole world? We wipe them all out, there’s not a single gun in the whole universe? People still get hurt, and they still can have bleeding,” Anderson said. “This course should not be affiliated with gun violence. This is about helping people that are bleeding in any scenario.”

The goal of the campaign has always been to train everyone, including children, said Dr. Kenji Inaba, chair of the Stop the Bleed Committee for the American College of Surgeons. Inaba said he taught his now-teenage son, an avid mountain biker, how to pack a wound and use a tourniquet by the time he was 10 years old. “He’s always in the middle of nowhere, by himself or with some friends, and I want him to know that knowledge.”

Inaba said that after discussion with pediatric surgeons, pediatricians and parents, the committee concluded that there really is no age limit on who should be taught these skills.

“Every child is different in their development. Every child is different in their experience,” he said.

Inaba added that the group is in discussion with child development experts and teachers to create a curriculum for younger kids.

Reaching kids where they are means designing education that meets not only their emotional needs but their physical needs. For example, Carleton explained to me that younger kids can more effectively put pressure and stop bleeding by using all of their body weight.

She showed the kids how to put their knee directly on the wound. “It’ll make it a little bit easier for you, and you won’t get tired,” she told them.

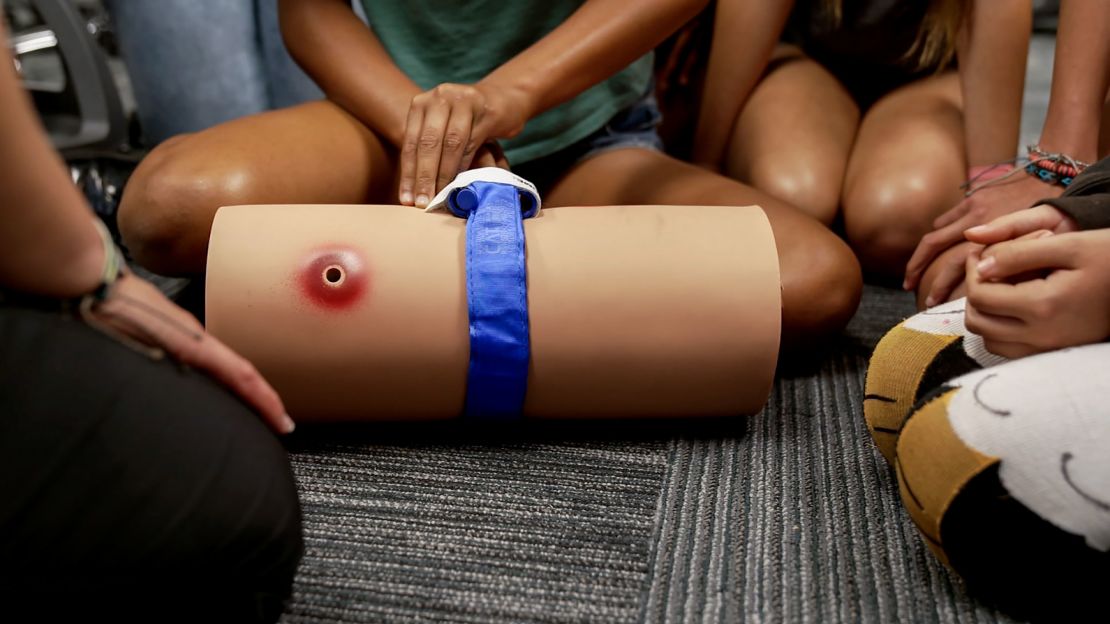

I watched as she stood in front of the class and demonstrated how to apply pressure with a rubber dummy limb, the same kind used to train EMTs. Carleton explained that adults will typically use their hands and press down as hard as possible over a packed wound, “because I’m stronger than you,” she said. One kid shouted out “Mom power!” and the class giggled.

Carleton then quickly divided the class into groups of four or five kids, led by volunteers from the fire department, to practice on dummy limbs.

“If you were in that situation, do you think you could do it now? Does that make you nervous at all?” I asked Harlow, a third-grader.

“Just the feeling of how it would be an actual person instead of a fake leg. That’s scary,” she said.

“But you think based on what you learned, if it was an actual person, you’d be able to do that?” I responded.

“Yeah,” Harlow responded confidently.

Even young children know how to help

Studies find that young people can learn lifesaving lessons. Though they aren’t as young as the students I visited, a 2019 study of high school students found that more than 80% of them were able to position a tourniquet correctly after being taught either in person or online. A small 2022 study of 11- and 12-year-olds found that 97% of the students grasped the lessons of bleeding control and tourniquet use after Stop the Bleed training.

A recent study from the American Heart Association found that children as young as 4 know how to call for help in a medical emergency and that by age 10 to 12, children can administer effective CPR.

Harlow’s classmate Jeremy told me that the best part of learning all of this was that he was prepared to help anyone. “It’s that feeling you get when you get to see them go to the hospital and know that they’re OK and the feeling that you’ve saved someone’s life,” he said.

And the lessons seem to stick with them. A sixth-grader, Piper, told me that although she would probably be nervous to apply these skills in a “real situation” when someone was “actually bleeding out and there was a puddle,” she was glad they had a trial run through the lessons in the classroom. “It kind of loosens things up and doesn’t make things so scary.”

Carleton’s daughter and Piper’s classmate, Quinn, agreed. “When a situation comes for something like this, it won’t be as scary, since we know what to do because we’ve already practiced it,” she said.

A new ‘stop, drop and roll’

As impressed as I was with how quick and engaged the kids were, I couldn’t help but feel sad that this is where we are as a country. A time when tourniquets and bleeding control kits are as routine as “stop, drop and roll,” the fire safety instructions that generations of children have learned in their classrooms.

When I shared that with Carleton, she told me that she felt the same way at first, but she had to change her approach.

“When I would initially go into that with that kind of feeling, I just found that I couldn’t teach the information in a way that it really resonated with them. It was being taught out of fear from me, and I don’t want that,” she said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

It is hard, however, to disentangle gun violence from the situations where these lessons could be most impactful.

Gun violence has become such a prevalent part of American life, Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has now issued an advisory calling firearm violence an urgent public health crisis. The advisory notes that half of children ages 14 to 17 worry about school shootings and nearly 60% of them have thought about “what would happen if a person with a gun entered” their school. According to the Gun Violence Archive, last year alone, 1,682 children died and another 4,512 were injured by gun violence.

So a grass-roots movement to train elementary-age children continues, with people like Carleton leading the charge.

“We can teach it, like teaching hands-only CPR or how to use an AED. It just becomes part of what we do,” Carleton told me. “It can be used in all situations, whether it’s a violent situation or not. But either way, it’s saving somebody’s life.”

CNN’s Nadia Kounang contributed to this report.