Editor’s Note: In Snap, we look at the power of a single photograph, chronicling stories about how both modern and historical images have been made.

A young Shaolin monk runs horizontally across a wall, intense concentration, and perhaps a hint of astonishment, visible in his face. Four other trainees at a martial arts academy near the Shaolin Temple in China’s Henan province lounge nonchalantly, seemingly unaware of the gravity-defying action taking place above their heads. Their bright orange robes and Feiyue sneakers stand in contrast to the earthen wall behind them.

The blurred back of a man on the left side of the image highlights the sharp movement at its center. A monk stretching in the background demonstrates his dexterity in a split-like stance.

“There’s this high-level action,” photographer Steve McCurry told CNN of the photo’s composition in a video call from his home in Philadelphia. “And these other boys are just hanging out.”

The image was recently featured in Magnum’s Square Print Sale in May, alongside other photographers’ works. He shot it back in 2004, as part of a personal project, while traveling the world to document various forms of Buddhism. While he doesn’t consider himself to be Buddhist, McCurry has long been interested in the religion and applies some of its principles to his own life.

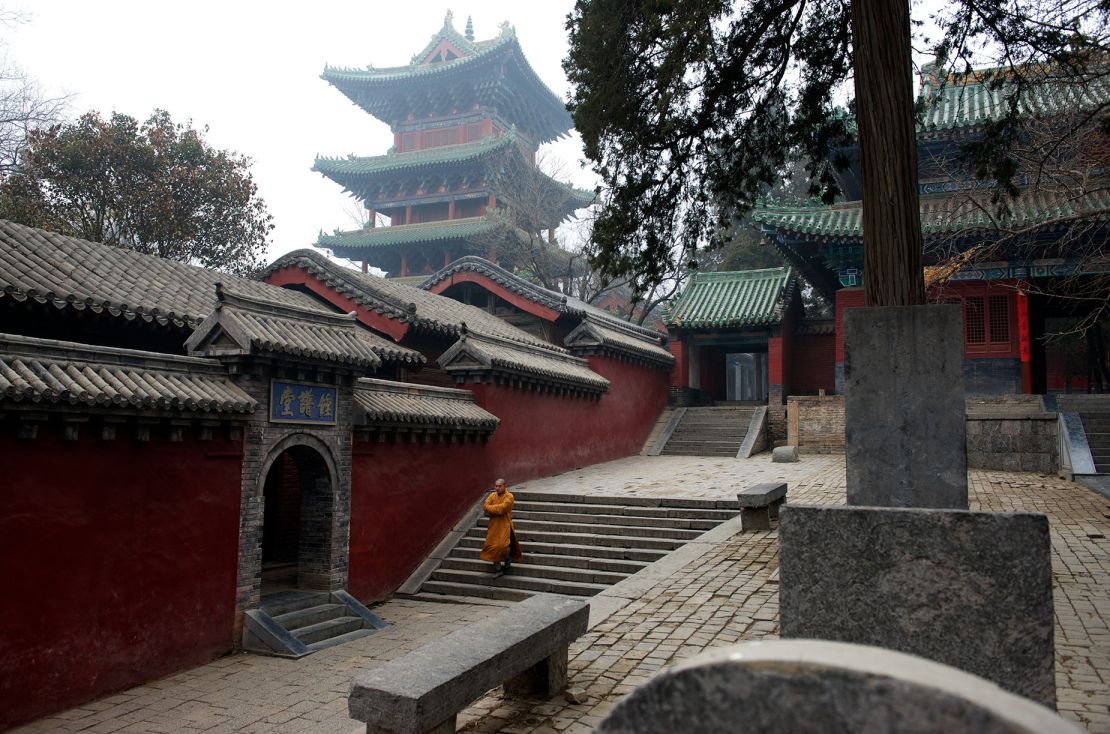

The Shaolin Temple – which was founded in AD 495 on the slopes of the sacred Mount Song – is said to be the home of Chan Buddhism. Although the religion emphasizes nonviolence, the temple’s warrior monks initially practiced martial arts to defend themselves from bandits. Over time, their rigorous physical training became inexorably linked with their quest to achieve enlightenment.

Today, Shaolin kung fu is widely known, and the monks’ feats in athleticism have been emulated in popular movies. The 1982 movie “The Shaolin Temple,” which launched Jet Li’s career and was filmed on location, was one of the films that brought renewed interest in the monastery. By the time McCurry visited in 2004, dozens of martial arts schools had sprung up on the road leading up to the temple.

“It’s incredible to watch them perform and train,” he said. “You can’t imagine that people can actually do that with their bodies.”

A career on the road

McCurry started his career working at a local newspaper after graduating from Pennsylvania State University. He then started traveling abroad as a freelance photographer, shooting images of people in some of the world’s most dangerous and remote places.

His career took off in earnest after he snuck across the border from Pakistan into Afghanistan in 1979, right before the Soviet invasion. He smuggled film out by hiding it in his clothing, providing the world some of the first photos of the conflict that left at least 500,000 Afghans dead and millions displaced.

His 1984 “Afghan girl” photograph – which captured the piercing green eyes of a 12-year-old refugee in Peshawar, Pakistan and was featured on National Geographic magazine’s June 1985 cover – is one of the world’s most famous photos.

Over the course of his 50-year career, McCurry, now 74, has filled more than 20 passports, snapping animals and festivals, worshippers and fighters, conflicts and catastrophes in destinations from Niger to India. He captures the ancient against the modern, the curious amid the day-to-day and accentuates the familiarity of strangers.

In 2016, McCurry came under fire when one of his photos in an exhibition was discovered to be digitally altered. He said it had happened in his studio while he was out traveling, but more images that appeared to be manipulated began surfacing, igniting a debate around the ethics of photojournalism.

In response to the allegations, the photographer told Time magazine later that year that beyond the brief stint at the local newspaper in Pennsylvania, he had never been employed by a newspaper, news magazine or news outlet. As a freelancer, he had taken on various assignments, including advertising campaigns. He said his work had “migrated into the fine art field” and that he considered himself a “visual storyteller.”

He added that he understood it could be “confusing … for people who think I’m still a photojournalist,” and that going forward, he would only use Photoshop “in a minimal way, even for my own work taken on personal trips.”

‘Going back again and again’

Before shooting the photograph of the wall-running monk, McCurry had already paid a visit to the Shaolin Temple two decades earlier. He says it was “really empty” during that first trip, and he saw only “bicycles and people in these Mao suits.”

By the time he returned, a kung fu craze had gripped the nation. The area felt more commercial, he recalled. Tens of thousands of (mostly) Chinese boys and men were inspired by a wave of kung fu movies, and were training at the dozens of schools in the area.

The photographer was granted permission at one of the academies and spent a few days with the monks as they went about their daily routine, which included practicing acrobatics on repeat. Some of the boys ate with McCurry at a noodle joint across the street, sharing their hopes to eventually land jobs in security services, performance troupes, as well as the entertainment industry. “They were normal kids,” he said. “But they were very, very dedicated and serious about this practice.”

He captured other photographs of monks’ intense training regimes during his stay, including several hanging upside down by their feet, hands calmly pressed into a prayer pose.

McCurry sought to find the right combination of variables like the subject, angle, light, and background, as the monks perfected their moves. “It’s a (matter) of photographing and going back again and again.”

His perseverance paid off. “It’s a picture that evokes a lot of emotion,” he said of the final shot of the wall-running monk. “It either brings a smile to people’s faces, or they’re kind of in awe of the physicality of these young boys.”