Last month, a jury convicted Jennifer Crumbley of four counts of involuntary manslaughter in connection to the 2021 Oxford High School shooting – one count for each student her son killed.

The historic trial, and stunning verdict, tested the limits of who’s responsible for a mass shooting.

The conviction potentially holds heavy implications for her husband, James Crumbley, who is facing the same charges and scheduled for trial Tuesday. He was the parent who physically purchased the firearm for their son and the one in charge of securing weapons in their Michigan home, his wife testified at her trial.

The prosecution of both parents, and an uptick in other criminal prosecutions and civil lawsuits tied to mass shootings, indicates attorneys are increasingly seeking to hold responsible people – and companies – who didn’t pull the trigger.

An ‘aggressive and innovative’ approach

Prosecutors over the past few years have been slowly, but steadily, expanding the notion of who can be held accountable for a mass shooting, said CNN Senior Legal Analyst Elie Honig, a former federal and state prosecutor.

While he cautioned each case rests on its own merits, “we’ve seen groundbreaking prosecutions of parents and security personnel,” he said, “and I’d expect that trend to continue.”

Aside from the Crumbleys, there have been other high-profile prosecutions of non-shooters in recent years: last year, the father of the Highland Park, Illinois, shooter pleaded guilty to seven counts of misdemeanor reckless conduct – like the Crumbleys, one count for each person his son killed after opening fire at a Fourth of July parade in the Chicago suburb in 2022.

The father, Robert Crimo Jr., struck a plea deal with prosecutors, downgrading felony charges stemming from sponsoring his son’s gun license application months after local police responded to reports of concerning behavior on the part of the younger Crimo.

Crimo Jr. was sentenced to 60 days in jail as part of the plea bargain and was released from jail in December of last year. The shooter’s trial is slated to begin in February 2025.

Lake County State’s Attorney Eric Rinehart, who prosecuted both father and son, told CNN he was willing to compromise the felony charges so the shooter’s father would face consequences – and to “put down a beacon that parents can be held responsible.”

Illinois State Police Director Brendan Kelly called the prosecution “aggressive and innovative” at a news conference after the plea deal was announced.

“You may not be the person pulling the trigger. You may not be the person with the firearm, but you could be held accountable for that conduct if you have knowledge that someone is a threat and you don’t act on that – particularly if you’re a family member and you fail to do that,” Kelly said.

And in a rare prosecution of a law enforcement officer over his response to a mass shooting, state prosecutors sought to hold a former school resource officer at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School accountable after he remained outside during the 2018 shooting that took 17 lives in Parkland, Florida.

The state brought child neglect charges under a Florida statute that governs caregivers, arguing Scot Peterson, as a school resource officer, had a duty to protect students.

Peterson was ultimately acquitted last year seven counts of felony child neglect and three counts of culpable negligence. After his acquittal, he spoke to reporters, saying, “the only person to blame was that monster,” speaking about the shooter.

Even in shootings with fewer victims, parents are being held accountable for the triggers their children pull: The mother of the Virginia 6-year-old who shot his first-grade teacher was sentenced to 21 months in prison for federal felony offenses last year, and a man in Michigan was the first person to be charged under the state’s new safe firearms storage law – spurred by the shootings at Oxford and at Michigan State University – after his 2-year-old daughter shot herself in the head with his gun.

The question remains whether prosecution of non-shooters will be effective in reducing the number of mass shootings in the United States. But undoubtedly, it has expanded prosecutors’ tool boxes, said Ekow Yankah, Thomas M. Cooley Professor of Law at the University of Michigan.

“It gives different prosecutors something to aim at – it gives them a new theory, it gives them something to try,” he told CNN. “It gives prosecutors who are frustrated, are facing a devastating crime, a mass shooting that’s hurt their community, some set of actions that they can take.”

Prosecutors can use the precedents set in cases like Jennifer Crumbley and Crimo Jr. in plea bargaining, Yankah said.

But the expanded ways of holding people liable, he warned, will result in more jail time in many cases, including those that don’t get high-profile press coverage like mass shootings.

“It’s always been the case that as prosecutors get more and more tools, the people who end up being prosecuted, or especially for vicarious liability, are almost always the politically most vulnerable,” Yankah said. “Especially people of color and the poor.”

Going after gun manufacturers and social media companies

No one was criminally charged in the Sandy Hook shooting that took the lives of 20 children and six adults in 2012. The shooter, like many other mass shooters, took his own life.

The shooter’s mother, who also was fatally shot by her son, legally purchased all the firearms recovered in the case. A state’s attorney report and a report by the state Office of the Child Advocate following the shooting revealed she declined multiple recommendations by medical professionals to treat her son for mental health issues and would discontinue his medications almost immediately after they were prescribed.

Ultimately, the state’s attorney concluded that the shooter was “solely criminally responsible for his actions of that day.”

Stephen J. Sedensky, who authored the state’s attorney report in 2013, told CNN his evaluation of the Sandy Hook case focused on and considered only the shooter’s behavior and not his mother’s role because he killed her before going to the school.

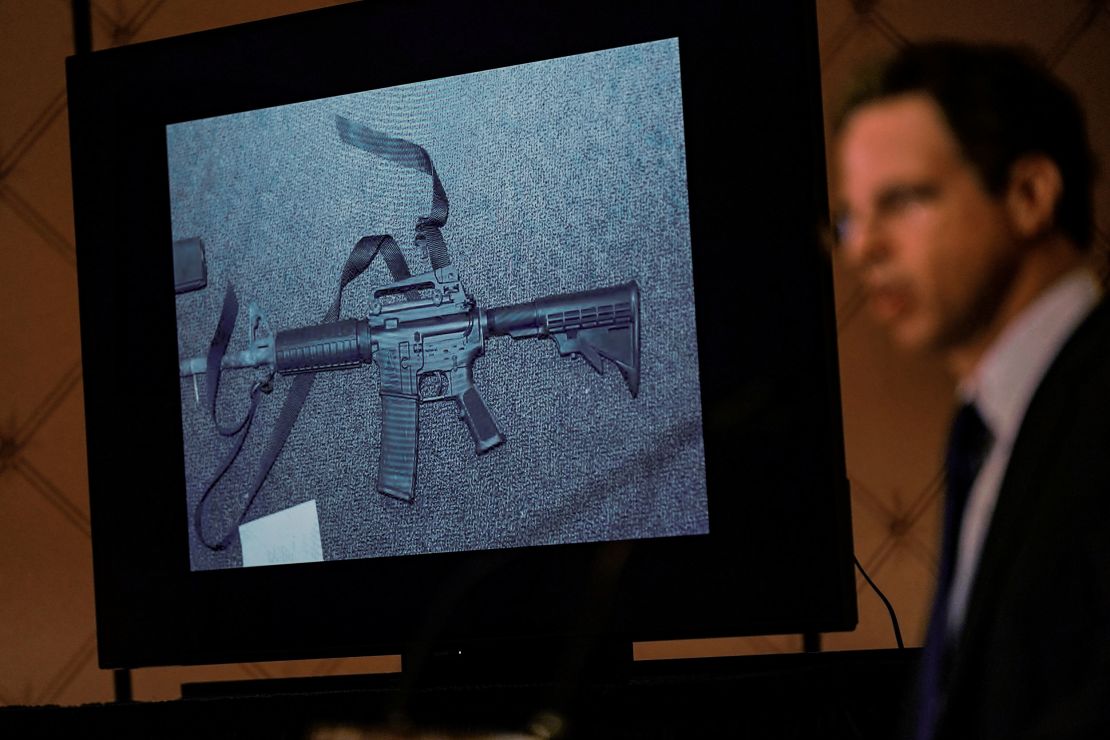

While there were no criminal charges in the Sandy Hook case, families of victims sought accountability in another way: with a landmark $73 million civil settlement with Remington, the now-bankrupt manufacturer of the AR-15-style rifle used in the massacre.

The families sued Remington in 2014, alleging the gun maker should be held partially responsible for the shooting because of its marketing strategy. A 2005 federal law protects many gun manufacturers from wrongful death lawsuits brought by family members – but the marketing argument was a new approach.

Others have followed suit: Survivors and family members of the victims who died in the racist mass shooting in a Buffalo grocery store sued social media companies, the shooter’s parents, and gun companies, alleging they facilitated and equipped Payton Gendron to kill 10 people and injure three others.

Federal prosecutors are seeking the death penalty against Gendron, who already is serving a life sentence after pleading guilty last year to New York state terrorism and murder charges.

Oral arguments have finished in the civil case, and the defendants have filed motions to dismiss the suit, said John Elmore, who is representing the plaintiffs. While attorneys are still awaiting decisions on some of the motions, one filed by a social media company and another by a gun manufacturer, have been denied, Elmore said.

And the family of a 10-year-old who was killed in the massacre at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas, filed a suit against nearly two dozen people and entities, including the gun manufacturer and store that provided the rifle used in the attack and law enforcement officials who responded to the scene.

Defendants in the case have also moved to dismiss the lawsuit and the parties are now awaiting a decision from the judge, according to Eric Tirschwell, executive director of Everytown Law, which is representing the plaintiff.

The Buffalo and Uvalde suits against the gun manufacturers follow the Sandy Hook methodology, targeting gun manufacturers for their marketing methods.

“There’s been, for about a decade, what you call innovative and entrepreneurial litigators who’ve been trying to impose what we think of as market share liability on a host of people, including most especially gun manufacturers, for producing weapons,” Yankah said.

“And so for many years, these cases have faced loss after loss after loss,” he said. “Slowly, I think you’re starting to see cracks in the armor.”