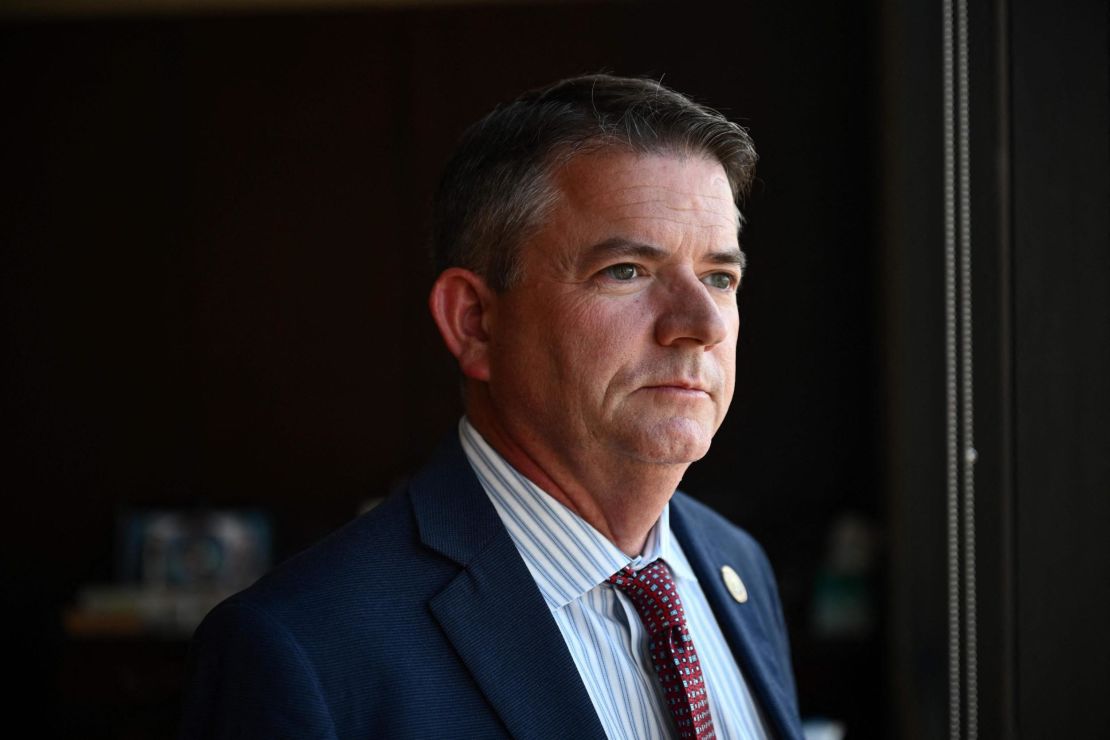

When Bob Bartelsmeyer accepted the job as the elections director of a sprawling rural county in Arizona last spring, it seemed like the perfect move. It was a step up professionally in a place where the Trumpian values of the community matched his own.

After all, Bartelsmeyer, 67, believed the falsehood subscribed to by millions of MAGA Republicans that the 2020 election was stolen from then-President Donald Trump.

But instead of getting a warm reception, Bartelsmeyer got a wakeup call: Not even he – whose social media posts promoted Trump’s claims of election fraud, was equipped to handle the extreme level of distrust in elections felt by residents in this county, which had become an unsettling case study in how democracy in an American county can break down.

Bartelsmeyer’s tenure in Cochise County, Arizona, lasted all of five months, and overlapped with a string of events that preceded his arrival and has kept swirling after his September departure. This has included the harassment of election officials by local election deniers and conspiracists, the refusal of an elected board to certify the 2022 midterm election, the criminal indictment of two GOP board members for their recalcitrance and the near disenfranchisement of tens of thousands of voters.

In his first national interview about the mess, Bartelsmeyer told CNN he fears the weakened democracy in this rugged county on the Mexican border is an indicator of where much of America is headed on elections.

“I have worries about the nation,” he said. “2024 is going to be very brutal. Going to be very hostile.”

In the aftermath of the 2020 election, Bartelsmeyer – who was not working as an election official at the time – posted memes and commentary on social media about how Trump was the true victor.

“Trump legally won by a landslide,” declared one meme that he reposted.

These posts from Bartelsmeyer have been removed, even though he still seems unable to fully shake his doubt about the 2020 election. The skepticism he voiced online drew scrutiny from critics and even made international headlines in April, when he was given the top election job in Cochise. What came next was a head-scratcher. Bartelsmeyer, who had previously been the election director in Arizona’s much smaller La Paz County, ran into a buzzsaw of opposition to his actions and proposals.

These included measures such as holding mail-only elections for special districts and continuing a yearslong practice of replacing neighborhood polling places with vote centers that enable people to cast ballots from anywhere in the county.

To Bartelsmeyer, they were common-sense moves that followed the law, made it easier to vote, saved money and were in line with regional and national election trends. What’s more, they were practices the county had already enacted in prior years without controversy. But to the dozen or so vocal detractors who showed up to Cochise Board of Supervisor meetings, they smacked of the kind of voting policies that aroused their suspicion that Trump was robbed in 2020.

In short, to them, their new MAGA elections director was not MAGA enough.

“After hearing that nightmarish thing from Mr. Bartelsmeyer – I was appalled by it, actually,” said one resident at the September board meeting where Bartelsmeyer recommended the voting centers. “To claim that he’s a conservative – you don’t need to claim it, it’s by your actions. And your actions, sir, are not that of a conservative, otherwise you’d be listening to your constituents.”

“Mr. Bartelsmeyer, if I had the authority, I’d fire you,” said another resident.

The critics tended to be light on specifics and heavy on suspicion when articulating their opposition. In general, they wanted to turn the clock back to a time when people showed up in person to an assigned neighborhood precinct to cast a ballot on paper that would be counted by hand. Some pointed out that most people in France still vote in this way. (However, that country also makes it easier to get to the polls by holding elections on Sundays.)

“I believe that if we continue to take these easy choices, and we go down this path of least resistance in the name of convenience, it’s not going to be too long before every vote is by mail,” said an attendee at the September meeting. “And then it’s not going to be too long til every vote is online. And then it’s going to be not too long until there’s no voting at all.”

“The reason we didn’t speak up when they put in these voting centers and things and vote by mail is because we were asleep at the wheel; now we’re awake,” said another. “You woke up a sleeping giant.”

One citizen believed that voting centers would somehow open the county’s election to “vulnerability so that (Meta founder Mark) Zuckerberg and those type of tech titans have a view into Cochise County.”

To top it off, the board ultimately voted to strike down Bartelsmeyer’s voting center proposal.

Bartelsmeyer told CNN the experience as election director in Cochise was “awful.”

“I’ve been ridiculed, disrupted and intimidated,” he said. “My reputation and ethics have been called into question. And I could not continue to work in an environment like that.”

Fed up with it all, Bartelsmeyer – who said the stress of the job exacerbated a health concern – resigned in September and returned to his former post as elections director in La Paz County.

Amid exodus of election officials, Bartelsmeyer’s story stands out

Bartelsmeyer is among hundreds of election officials or workers across the country who have left their jobs in recent years, according to several national voting rights groups, raising concerns about the upcoming presidential election. In polls and news articles, election workers say they’ve faced unprecedented hostility in the form of harassment and threats.

The strife – and resulting exodus – has been especially pitched in the American West and in battleground states such as Georgia and Michigan. Across 11 western states, more than 160 top local election officials have left their positions since November 2020, according to a recent report by Issue One, a nonprofit election watchdog group. In Arizona alone, at least a dozen of the state’s 15 county election chiefs have departed since the 2020 election, according to the report.

They include Geri Roll, the former election director in Pinal County who says top local Republican officials falsely accused her of all manner of wrongdoing, from not counting ballots to changing votes.

“It was so toxic, I had to resign,” said Roll, an attorney – and former registered Republican – who has worked as an assistant attorney general for Arizona and a county prosecutor. “I have dealt with defendants who are rapists, murderers, child molesters. Their correspondence was far more respectful than anything I saw on elections.”

Bartelsmeyer’s story stands out for how he’s an election officer and a onetime election denier – one who, in his professional capacity as Cochise election director, was aghast by what he considers the outlandish claims of local citizens in rural Arizona who appear to trust no election officials, and believe an effort to steal elections and strip away their sovereignty is afoot.

And yet, Bartelsmeyer doesn’t completely disavow his earlier skepticism of the 2020 outcome. He still maintains that “there was just something off” about the 2020 election, although he told CNN that Joe Biden “probably” won.

Later in the interview, Bartelsmeyer asked to revise his statement on Biden’s victory. “I think we should say, yes, he is president,” Bartelsmeyer said, though he added: “Sometimes it’s hard for me to accept that there wasn’t some errors made in the election, but I’m not sure that it was to the extent that it would have changed the election.”

Ultimately, he said, “the secretary (of) states’ offices across the country … certified the elections that Joe Biden won.”

Bartelsmeyer’s selection to the job in light of his social media posts – and his lingering doubts about 2020 despite his professional commitment to fair and free elections – are signs of a messy time for democracy in America, where, as of late summer, nearly 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents still questioned the legitimacy of Biden’s victory, according to a CNN poll.

‘How can anyone make these people happy?’

Prior to Bartelsmeyer’s April arrival to the county of 126,000 residents tucked in the southeastern corner of Arizona, the election office was already awash in scandal.

His predecessor, Lisa Marra, quit under duress early last year after citing threats from residents and a clash with the board of supervisors, which she said unsuccessfully tried to pressure her to conduct an illegal hand-count of the ballots after the 2022 midterm election – and even sued her for her refusal.

“I could have just stayed and been harassed,” Marra told CNN. “But I think the writing was pretty clear on the wall that you can’t stay to work for people that sue you personally for refusing to break the law.”

That same board of supervisors was fighting with the state. Because of their mistrust of voting machines, the two Republicans on the three-member board were refusing to certify the 2022 election results. This prompted a lawsuit filed against the county by the secretary of state – now the governor. A judge ultimately compelled the board to certify.

It was against this backdrop that Bartelsmeyer was brought on last spring. At first blush, it looked like a case in which he might be a better cultural fit, given his pro-Trump social media posts, some of which earned misinformation tags on Facebook.

However, Bartelsmeyer said, he was eventually met with the same hostility from the residents that chased out Marra, who later won a $130,000 hostile-work-environment settlement against the county and is now the deputy director of elections for Arizona.

“How can anyone make these people happy?” Bartelsmeyer said. “You can’t. You can’t make these critics happy.”

In late November, the two Republican board members – Peggy Judd and Tom Crosby – were criminally indicted by a grand jury for their initial refusal to certify the 2022 election. Each was charged with two felonies: interference with an election officer and conspiracy, according to the indictment. Both Judd and Crosby, who have pleaded not guilty, declined interview requests through their attorneys.

And yet, despite all the turmoil stemming from election denialism – and despite what he says was his own mistreatment at the hands of election deniers – Bartelsmeyer still grapples with how the 2020 election went down.

An election official wrestles with his own election doubts

Echoing talking points in MAGA circles, Bartelsmeyer said he is puzzled by the large number of votes received by both Biden and Trump, with Biden’s tally exceeding 81 million and Trump’s – at 74 million – surpassing what he’d gotten when he won in 2016.

“The margin to me doesn’t sometimes add up,” he said. “That question, you know, that Trump could receive 10 million votes more than he did before in 2016. How did that happen?”

Pressed by CNN in the interview on how the hefty popular vote counts of 2020 have been widely attributed to high turnout, Bartelsmeyer neglected to respond, pivoting instead to his concerns about the pandemic, which was still raging during the presidential election.

“The election itself just didn’t seem like it had been in the past elections,” he said. “There was just something off.”

Bartelsmeyer added that the scaled-back campaign season caused people to rely more heavily on social media. And he noted that the act of voting itself was profoundly changed by the deadly health crisis.

“States adopted more of a lenience of mail ballots, of people not voting in person, where you have more control,” he said, adding that he questions whether some states had done enough to verify signatures on ballots.

Trump and the GOP in 2020 called for election officials to match signatures on mail-in ballots with signatures on file – or to throw out all mail-in ballots in counties with a high rate of match issues. In Pennsylvania and Georgia, judges rejected those efforts on the grounds that they would have run counter to state election laws already in place.

Still, Bartelsmeyer says that by and large, “America should have confidence in the democratic way of elections.”

He said politics “has no place in election offices” and expressed dismay about the growing distrust, mostly in rightwing circles for now, of electronic voting machines, and what he said is the false belief they are connected to the internet and can be hacked.

“We’re going backwards,” Bartelsmeyer told CNN. “We’re going to a primitive time period.”

Sharing Bartelsmeyer’s concerns about the 2024 election is another Arizona official who has taken a public lashing for standing up to election deniers. Bill Gates, a Republican, was among several members of the board of supervisors in Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, who were inundated with threats after they certified the results of the 2020 election, marking the first time in about a quarter century that a Democratic presidential candidate – Biden – won the state.

“During the holiday season of 2020, I had posted our holiday card on Instagram, and the comments included the suggestion that our daughters should be sexually assaulted,” Gates told CNN. “That was a line that I never imagined could be crossed.”

While Gates worries that more election officers could be election deniers – as Bartelsmeyer once was – he also believes more officials should speak up – as Bartelsmeyer is doing – for election workers who are under siege for trying to do their jobs.

“A lot of Republicans, friends, colleagues who I’ve worked with for many years have come up and whispered in my ear: ‘Keep up the good work, Bill. You and the team Maricopa County, you’re doing a great job,’” Gates said. “But they don’t want to speak publicly because they have seen what has happened to others.”

The country, he said, is approaching a crossroads.

“It’s almost a cliche to say this is the most important election of our lives, but I truly believe that,” Gates said. “I do believe this is the one we got to get right to keep this democracy going.”