Osmic Menoe was a young kid in South Africa when he first fell in love with hip-hop culture during the late 1980s, at the height of the country’s anti-apartheid movement. But like so many, at first, he didn’t even realize what it was.

“I got into the culture visually … seeing murals seeing people spraying graffiti,” he explained. “I used to like making different sounds with my mouth. I didn’t know that’s called beatboxing.”

Menoe grew up to realize the elements of hip-hop that he loved went hand-in-hand with history and culture across the continent. “Africa is the beat, Africa is the soul,” he said.

Yet little had been documented about the origins of the genre there, or the people who took it to new heights.

“What’s going to happen when all these individuals pass away, and no one remembers the story?” Menoe said. It inspired him to start the South African Hip-Hop Museum in Johannesburg, and the Back to the City Festival.

“We can capture all these stories so that future generations can know what all these people were doing and be inspired,” he said. “The world has been operating on African [cultural] resources, not just on our minerals.”

2023 marks what’s considered by many to be the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, but the origination of the genre continues to be one of the most debated topics in all music. Although most enthusiasts agree the birthplace of hip-hop was in the New York City borough of the Bronx, many believe the artistic foundation of the genre can be traced back to Africa.

With such a rich history, CNN set out to track down the answer to another timeless hip-hop debate: which really came first? Did Africa influence hip-hop culture? Or was it influenced by the culture?

From Africa to the Bronx and back

It’s widely believed that 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx was the birthplace of the hip-hop genre, and it all began with DJ Kool Herc. On August 11, 1973, his sister Cindy Campbell requested he spin some records at her “Back-to-School” jam at the 1520 Community Center, he once told NPR in an interview. There, the Jamaican-born DJ first tried out his “Merry-Go-Round” deejaying style on the turntables, extending an instrumental break to let people dance (breakdancing) longer and began MC’ing (rapping) during the extended groove.

While this infamous party has its place in hip-hop history, the roots of rap extend back much further, spanning the Atlantic.

Dating back to the 13th century, storytellers called “griots” existed in West African kingdoms and empires. Historically, griots have been highly skilled orators, poets, musicians, praise singers, and satirists who traveled around reciting the history of the empire with rhythm and repetition. This widely recognized oral tradition, some argue, could be considered the earliest manifestation of rap, laying the groundwork for the development of hip-hop.

“Rap is fundamentally based on vocal styling, based on call-and-response, which is the foundation of all Black music,” said Obi Asika, a Nigerian entrepreneur and record executive who was instrumental in growing the country’s music industry.

Call-and-response, where one phrase answers another either vocally or instrumentally, was popularized through artists such as James Brown (himself inspired by gospel music). It was brought to the forefront of hip-hop in the history-making 1980 Kurtis Blow track, “The Breaks” – with a foundation that can be found throughout African history.

“Ogene music [from the Igbo people] is at least a thousand years old; it’s call-and-response. If you listen to the Orikis in Yoruba with a priest singing, it’s call-and-response. If you listen to the foundations of Fuji [from the Yoruba people], it’s hip-hop,” Asika reflected, citing various music styles of different Nigerian ethnic groups.

“Music is a ritual for us in Africa, it’s not just entertainment,” he added. “Music is embedded in the form and function of African society from day one because it is also tied to the metronome of our hearts.”

Tracing hip-hop’s steps back to Africa

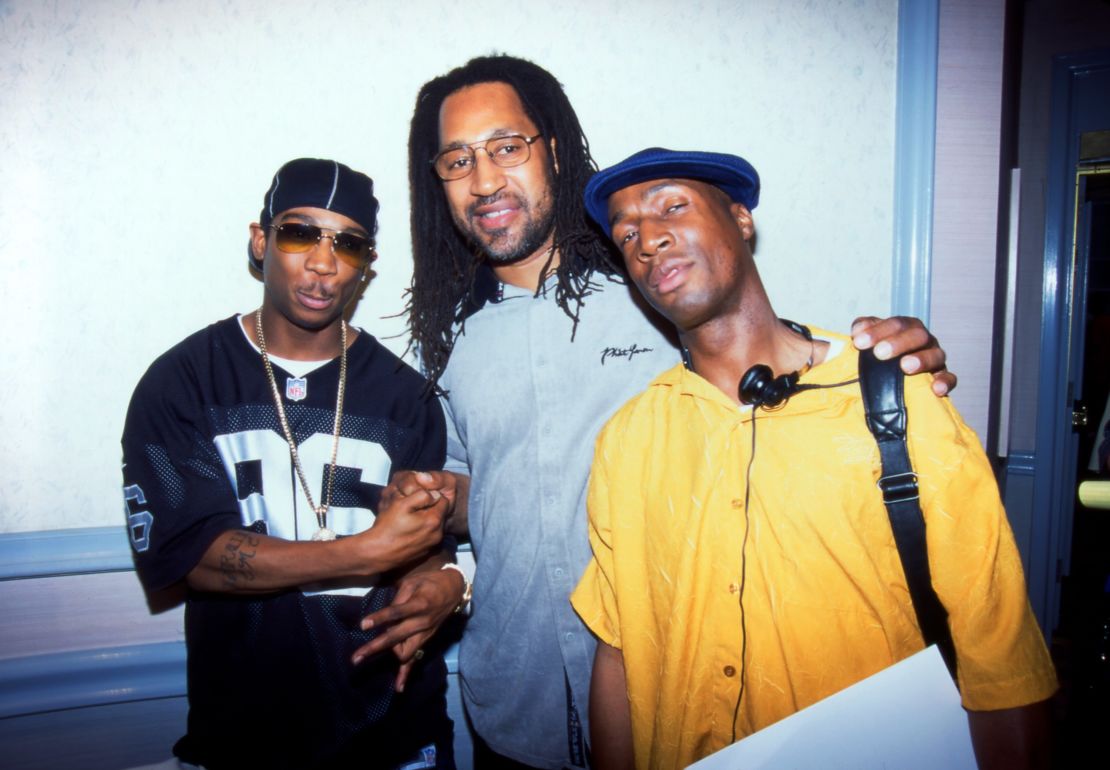

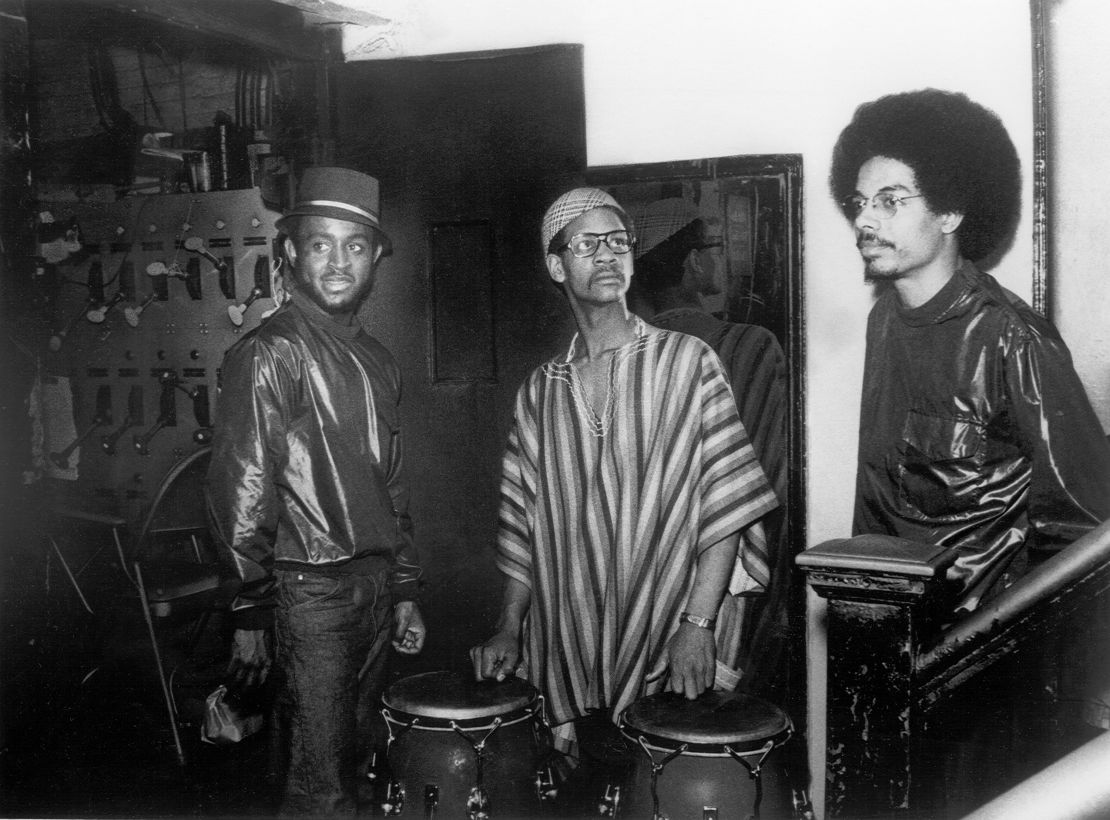

Five years before the party on Sedgwick Avenue, a group called The Last Poets provided the first known of glimpse of Africa’s influence on Western hip-hop culture, during the American Civil Rights movement.

The group of activists, poets and musicians, often credited among hip-hop architects, gathered in what is now Harlem’s Mount Morris Park on May 19, 1968, what would have been the 43rd birthday of assassinated civil rights leader Malcolm X, and recited their first poems in public. By 1970, they released a self-titled album of recited poetry amplifying Black power to the beat of a conga drum.

The group’s vocal style also includes aspects of call-and-response and rhythmic chanting based in African culture.

Even the name, The Last Poets, was inspired by words from the continent, with a poem called “Towards a Walk in the Sun” by revolutionary South African poet Keorapetse Kgositsile. In the poem, Kgositsile depicts a time when poetry would have to be set aside in the face of the revolution.

The group’s body of work has since been sampled or referenced by the likes of Common, Too Short, N.W.A, a Tribe Called Quest, and The Notorious B.I.G. (founding Last Poets member Abiodun Oyewole actually filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against the artist’s estate, which was dismissed in 2018 and deemed fair use).

The spoken word element, dating back centuries to the griots, and then evolving to include musicians, poets and rappers, has played a crucial role in preserving oral history and cultural richness.

Asika agrees that without the African blueprint, aspects of rap in hip-hop culture would cease to exist. “The music that the Black Americans have generated is music coming from their original source as Africans, which they have now reinterpreted because of the environment they are in,” said Asika.

“All Black music, including hip-hop, comes from us.”

The song that sent hip-hop around the world

The global notoriety of hip-hop began with the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979.

“Everybody heard that record,” recalled Asika.

At the time, rap was referred to as “electro-funk,” and “Rapper’s Delight” was the first to be played on the radio.

“We were really consumed by American hip-hop rap music,” said Ayo Animashaun, founder of Hip-Hop World Magazine and executive producer of The Headies awards, which celebrate Nigerian music.

“We lived the culture, not by location, (but) by association,” Animashaun added.

Asika agrees this sparked a cultural shift on the African continent, leading fans to embrace the five elements of hip hop: emceeing, deejaying, breaking, graffiti, and beatboxing.

“Those five things, that’s hip-hop. That’s how the culture came alive,” he said.

Pioneers of African hip-hop

Like in America, the DJ was the first to put rap on the map in Africa.

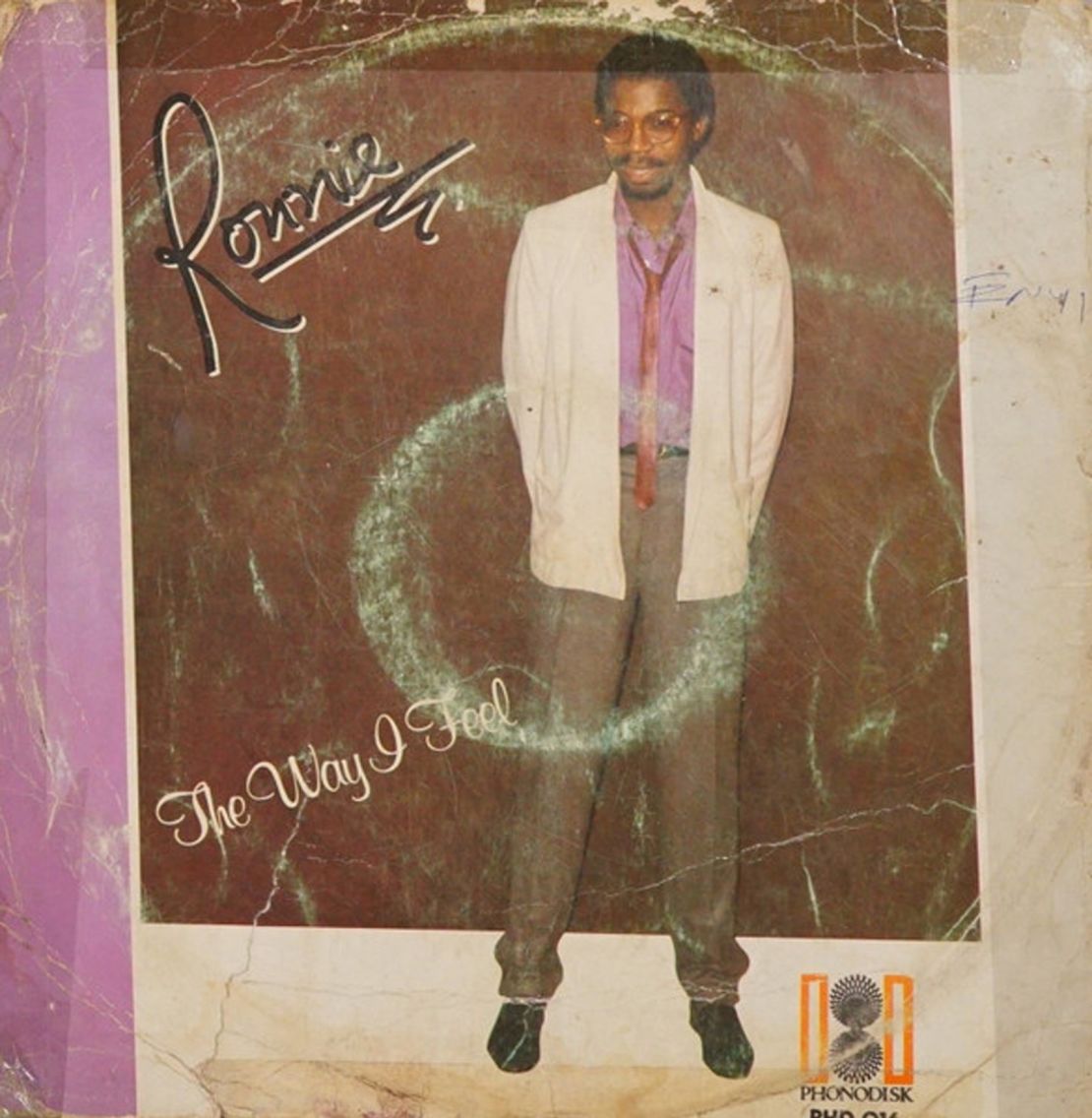

“Ron Ekundayo seems to have had the first record that was maybe recognized beyond Africa,” said Asika of the continent’s earliest hip-hop offerings.

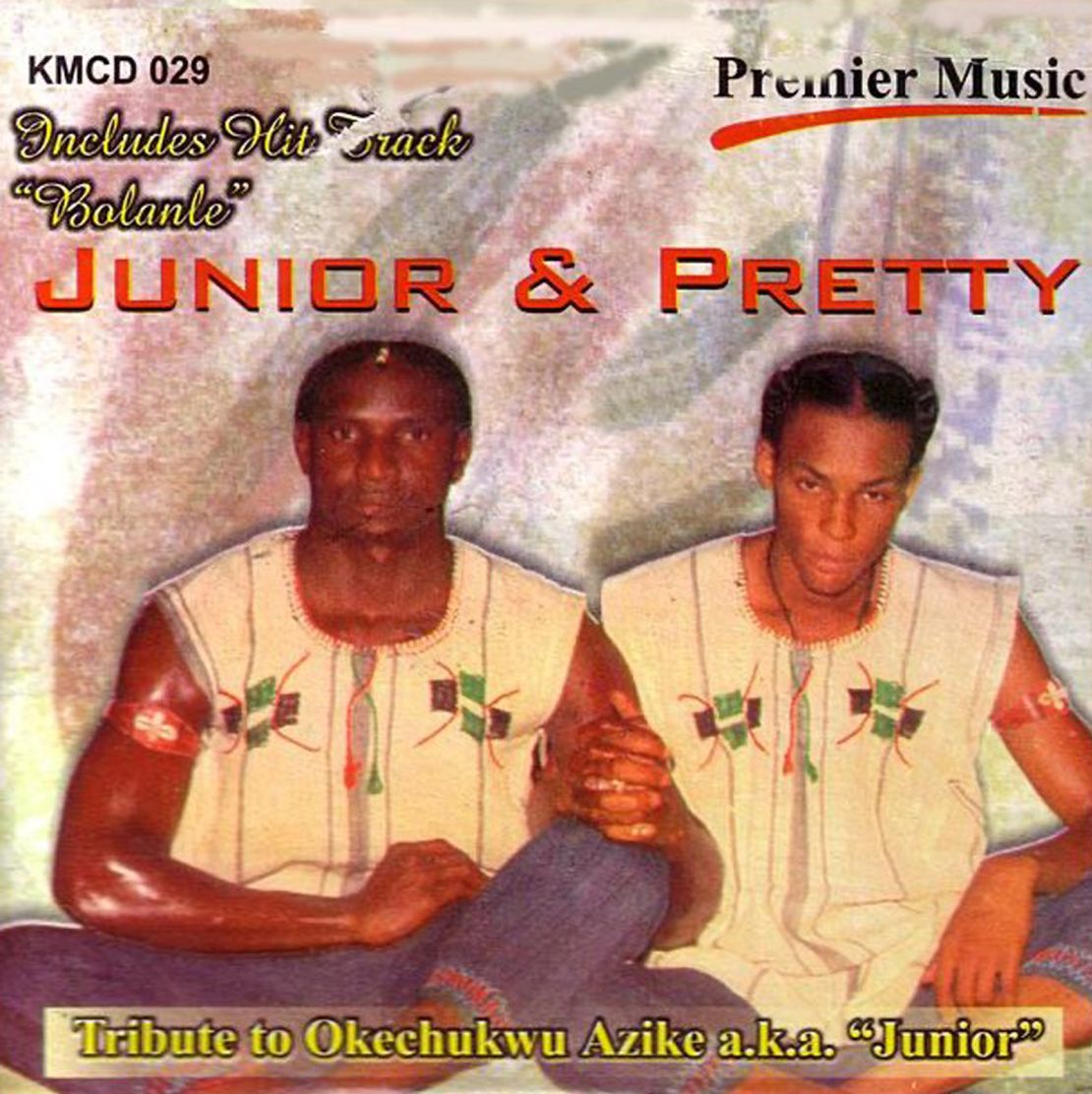

Nigerian disc jockey Ron Ekundayo a.k.a DJ Ronnie, released “The Way I Feel” in 1981. Considered Nigeria’s first rap album, it pre-dates the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, when the genre really began to dominate mainstream music. DJ Ronnie’s pioneering album led the way for the powerhouse Nigerian duo Okechukwu Azike and Pretty Okafor, better known as “Junior and Pretty.”

“They were actually rapping, they were preaching, they were telling stories with their rap,” said Animashaun.

Junior and Pretty were among the first Nigerians to commercially release rap music.

“I believe they are the foundation of Nigerian hip-hop and the foundation of Afrobeats,” said Asika, who signed the duo in 1992 to Storm Records and released their first pidgin album.

At a time when most artists were copying American hip-hop culture, the duo stood out, bridging local dialects with English, which was considered unique at the time.

“Their music is the foundation of everything everybody has done since then,” Asika added.

“[Hip-hop] started to become dominant and take over, and then the transition is that when we fully domesticated hip-hop, it became Afrobeats.”

Meanwhile, the 1980s in South Africa brought Senyaka Kekana, known professionally as just Senyaka. The late rapper, who is recognized as one of the country’s earliest hip-hop acts, released his debut album called “Fuquza Dance” in 1987. With hit singles including “Go Away,” the rapper experimented with fusing music genres like house and pop music, splicing in his own humorous and sometimes controversial lyrics. Senyaka’s signature style also laid the foundation for the sub-genre of Kwaito, a house music variant featuring African sounds and samples.

The birth of a protest movement

Against the backdrop of Nigeria and South Africa’s hip-hop evolution, the Senegalese rap scene was bubbling up. By the late eighties, hip-hop influence reached the French-speaking country in West Africa.

“Senegal is a huge hip-hop hub,” said Leslie “Lee” Kasumba, an African music curator out of Uganda.

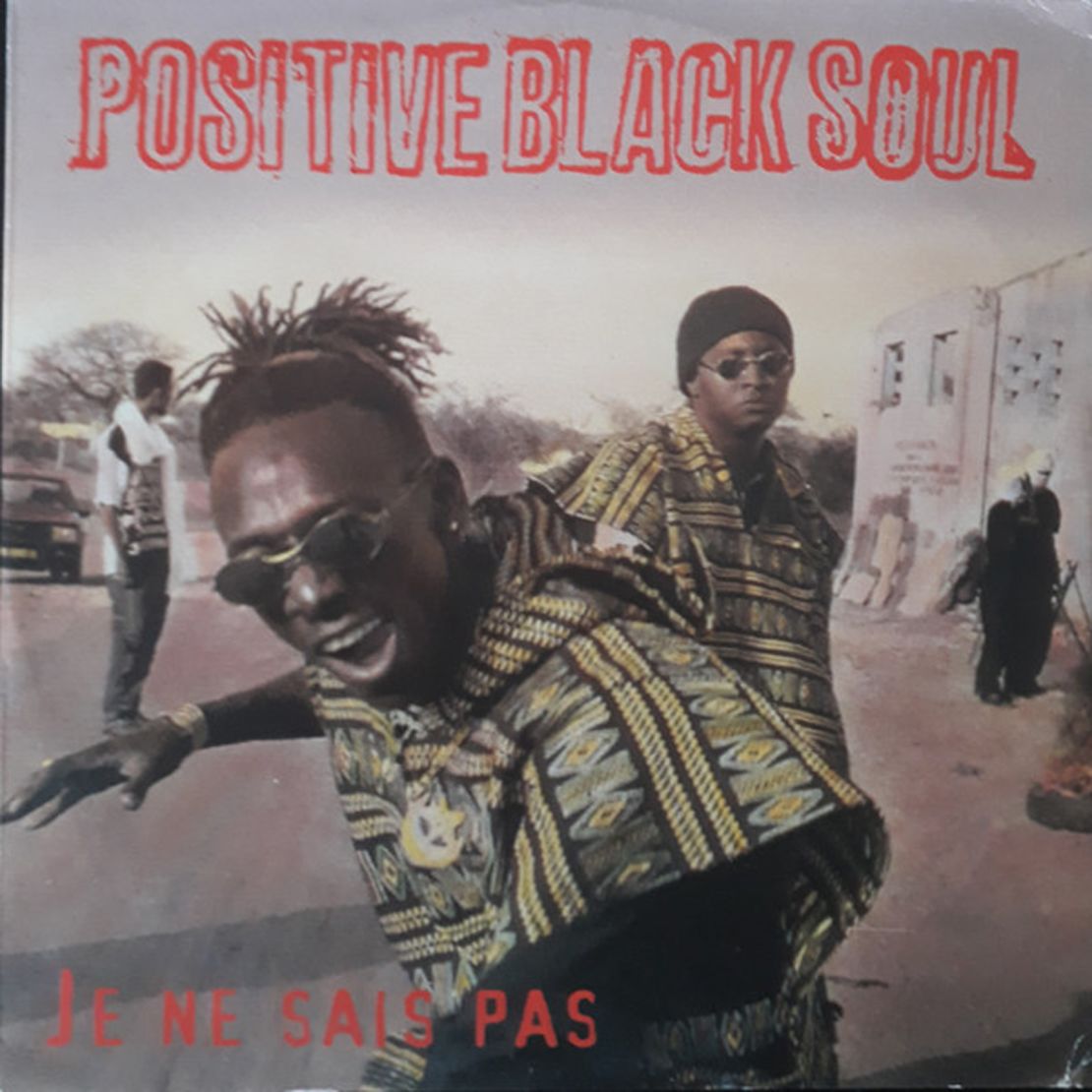

While Eric B. & Rakim were changing rap’s flow in America with their album “Paid in Full,” Senegal had a dynamic duo of their own developing with Positive Black Soul.

The Dakar-based duo featuring DJ Awadi and Doug E. Tee became the country’s first well-known hip-hop group. The group was founded in 1989 and flowed in English, French, and Wolof. Mirroring American artists like Public Enemy, the duo was pro-Black and their lyrics focused on African pride.

“Outside of being great rappers and everything, they were also involved in the community,” said Kasumba.

By the mid-1990s, conscious rap was seeing an uptick in popularity worldwide. Beyond the good times and party vibes were lyrics that raised awareness of community social turmoil.

In 1993, the Tanzanian group Kwanza Unit was another early adopter of the trend. Kwanza Unit was a hip-hop collective similar to Wu-Tang Clan, which formed in the US the year before. The group operated as a community bringing together artists and fans to establish their own culture and way of life. Like Public Enemy did for the US, the group’s lyrics addressed racism, classism, police brutality, and other social issues faced by the people in Tanzania, but the delivery was in Swahili.

And what Osmic Menoe remembered from his time as a young child in apartheid South Africa was emerging, particularly in Cape Town, with deep roots in hip-hop protest music.

The long-term inequities faced by many Black people there inspired artists to use music as a way of speaking out against hardships in South Africa.

Prophets of Da City was the first known hip-hop crew on the scene reflecting this approach.

“Groups like Prophets of Da City were super vocal about being community activists, and they were quite politically driven,” said Phiona Okumu, Spotify’s head of sub-Saharan Music, a group charged with elevating African acts.

Okumu, who worked as a journalist in South Africa during the early stages of hip-hop, cites Prophets of Da City as one of the most influential acts of its time.

“They reminded people of similar groups in the US like Public Enemy, groups like this who were very militant and quite concerned about the human condition,” said Okumu.

“They rapped often about what was happening in their immediate reality being from the Cape Flats,” she added, “and that was really what the start of grassroots hip-hop in Cape Town.”

Swagger like us

On the shoulders of these giants, African artists began to see more widespread commercial success at the turn of the century. In Nigeria, the name that comes up the most is Mode 9. “It was real hip-hop,” the artist told CNN of the music of the era.

Born in England as Banatunde Olusegun Adewale, Mode 9 (or Modenine) is a DJ-turned-rap star who started out as a presenter for Rhythm 84.7 FM in Abuja, Nigeria. He made his musical debut in 2004 with his album “Malcolm IX.”

The nine-time Headies award winner, including seven for Lyricist on the Roll, is known for his wordplay. But even the trendsetter has US hip-hop influences of his own.

“When I listened to [American rapper] Big Daddy Kane, everything changed,” Mode 9 said. “He inspired me to just be who I am, (to) not be afraid to add that to my hip-hop.”

For most aspiring African rappers in those earlier years, the key to success was mastering the art of American hip-hop swagger.

“It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at – a hip-hop state of mind,” Mode 9 said. He recalls wearing head warmers, Champion hoodies, and Timberland boots to embody hip-hop swag, even though temperatures in Lagos didn’t usually cooperate.

“We didn’t give a damn whether it was hot or not; you would see us sweating, wearing our head warmers, trying to look hip-hop,” he said.

A lasting fashion movement came hand in hand with hip-hop’s mainstream popularity. Early on, American artists often rapped about clothing brands they wore. Graffiti artists went from tagging to airbrushing outfits, while break dancers were creating their own signature sense of styles.

“The dress code was straight out of a Source Magazine,” explained Mode 9, referencing the US-based publication, which is the world’s longest-running rap periodical.

“What was hot in America was definitely hot in Nigeria,” he added.

“I’m wearing Adidas – that’s purely because of hip hop,” agreed Menoe. “But subconsciously, the reason you chose to go buy that shoe is purely because there was a group called Run DMC that made it popular and that made it look cool.”

Rap’s roots grounded in Africa

While both Asika and Menoe agree rap music has undoubtedly influenced various global music scenes for the last half-century, including across Africa, its origins lie in African cultural expressions, reciprocating the influence.

“I don’t want it to look like Africans are trying to appropriate something that our cousins created,” said Asika. “I think in Africa, hip-hop is maybe a thousand years old. So, with us, music is deeper than just some ephemeral thing; it’s fundamental.”

With the skyrocketing global popularity of Afrobeats, African acts have recently been dominating the music landscape, but more needs to be done to document the history of hip-hop and its evolution on the continent. That’s why Menoe is so passionate about teaching and preserving Africa’s hip-hop history, and his driving purpose for establishing the museum in South Africa.

The museum enshrines artifacts and includes a wall of fame, which pays tribute to those who laid the foundation for today’s hip-hop.

“We want to show the world what Africa’s about,” said Menoe.

“This (hip-hop) is what we are about, and this is what we’ve been about.”

CNN’s Earl Nurse, Kaito Au, Aneta Felix and Gertrude Kitongo contributed to this report.