In the parking lot of New Jerusalem Church in Jackson, Mississippi, volunteers handed out free cases of bottled water to a line of arriving cars last week – a new normal in a state capital that has struggled with the fallout of a failing water system.

But inside the church, a parade of pastors and organizers addressing the crowd railed against another threat they described as dire to the city’s future: their state legislature.

Republican state lawmakers are pushing “a takeover of the city of Jackson and disenfranchising local voters,” declared Danyelle Holmes, a local activist. “They’re banking on us to be quiet. They’re banking on us to back down.”

The T-shirt she wore underscored the political mood of the event – and the siege mentality that city leaders say they’re feeling: JACKSON VS. EVERYBODY.

A proposal in the Mississippi legislature to reshape Jackson’s criminal justice system has erupted into a high-stakes battle between the Republican-dominated state government and the Blackest big city in the US over some of the most incendiary flashpoints of American politics: voting rights, public safety and race.

The fight comes at a time when the legislature is debating other bills that would also narrow the city’s authority, including over its broken water system. And around the country, other Republican-controlled state legislatures are also clashing with big-city leaders over power struggles and purse strings.

The Mississippi criminal justice bill, which passed the state House of Representatives earlier this month, would create a new, separate court system in a district that includes Jackson’s downtown and a third of its residents. Judges and prosecutors in the district would be appointed by state government officials, encroaching on the power of locally elected judges to hear some cases.

A modified version of the bill stripped of some of its most controversial provisions passed a state Senate committee Thursday – although they could be added back in as the two legislative houses come to an agreement.

Both versions of the legislation would greatly expand the jurisdiction of the Capitol Police, a state government-controlled police force that has been criticized by local leaders for aggressive tactics and multiple shootings by officers.

Taken together, the changes in the House bill would put White, conservative state officials in control of much of the criminal justice system across a significant swathe of Jackson. That prospect has mobilized opposition in a city where more than eight in 10 residents are Black.

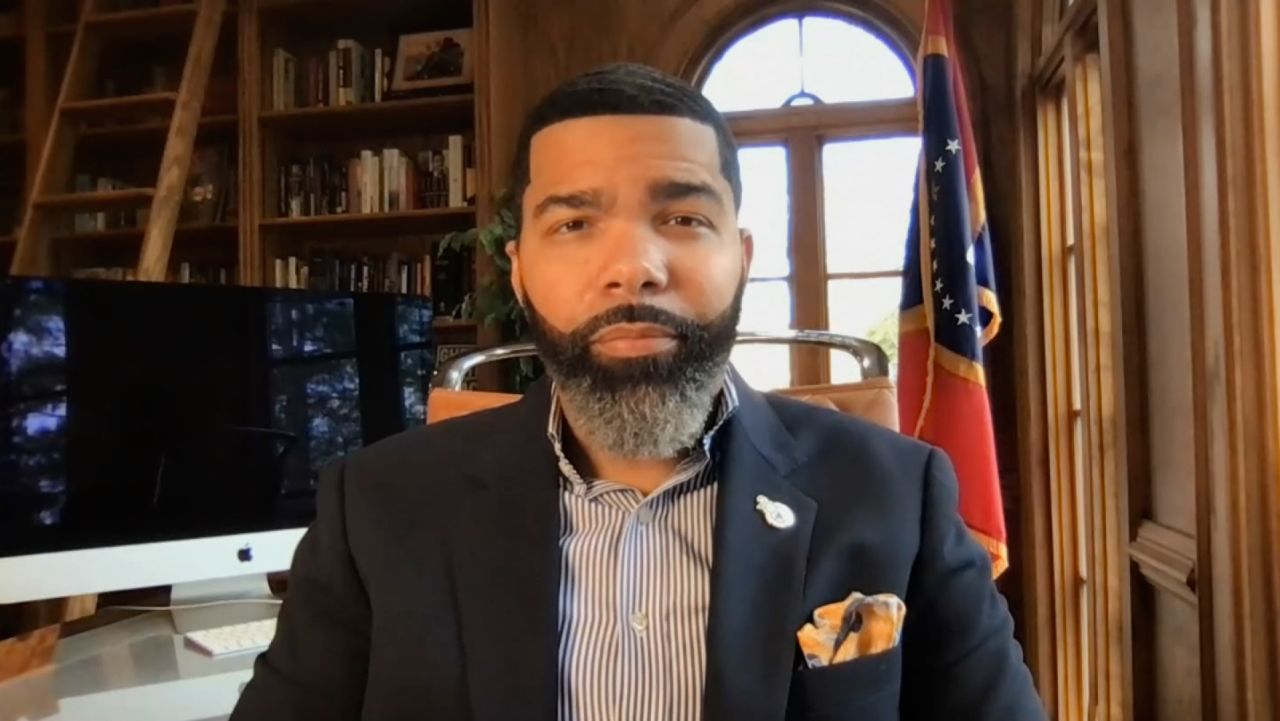

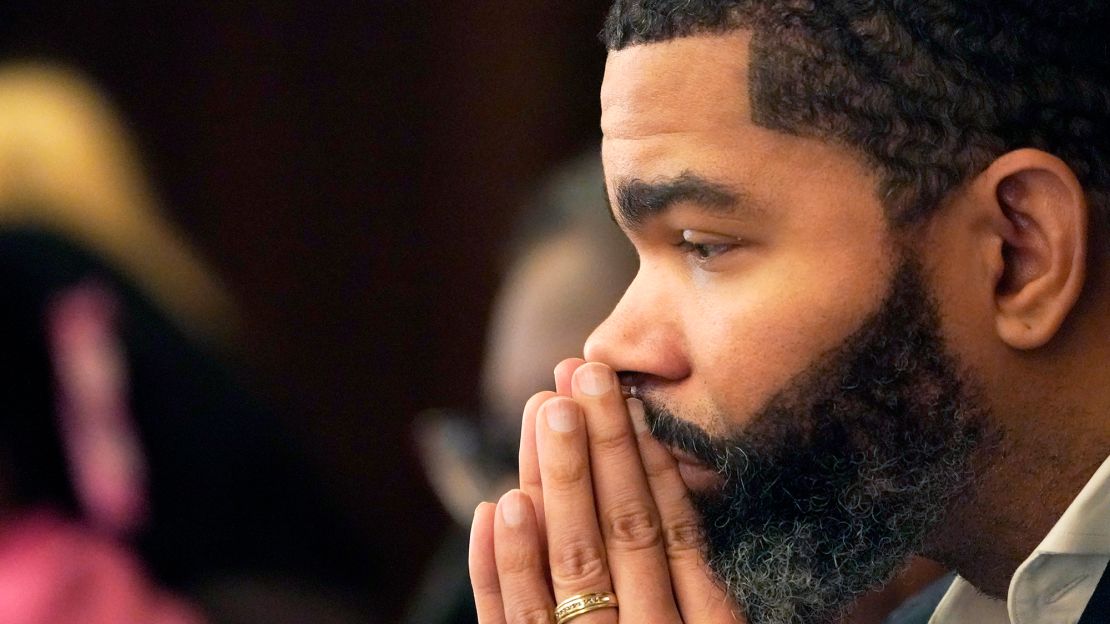

“It is taking us back in time and it puts us on the wrong side of history,” Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba said in an interview. “It’s colonization, it’s apartheid, it’s the worst of what Mississippi can be.”

The GOP lawmakers pushing the bill say it’s needed to address huge court backlogs and stem violence that spiked in the city in recent years. Jackson reached a record number of homicides in 2021, with one of the highest murder rates in the US, although the number fell last year.

“The bill is totally racially neutral,” its sponsor, Rep. Trey Lamar, told CNN this month. “I hate that the other side used race as much as they did.”

Cliff Johnson, a University of Mississippi law professor and the director of the university’s MacArthur Justice Center, said the House version of the bill stood out for its audacity.

“You’d have a police department and judges and prosecutors who aren’t accountable to local voters, all of whom are appointed by White officials in a city that’s 82% Black,” he said. The bill, he added, is “the most radical piece of legislation I’ve seen in 30 years of practicing law in Mississippi.”

A radical bill

One of the few things that state and local leaders in Jackson agree on is that the city is facing steep challenges – from the breakdown in water infrastructure, to the spike in murders, to a dramatic drop in population that has sapped the city’s tax base.

As White residents moved out to the suburbs, Jackson’s population fell nearly 25% from 1990 to today. At the same time, the city went from about 56% Black then to about 83% Black now – the highest percentage of any major city in the US.

In 2017, state legislators aiming to help support the city created the “Capitol Complex Improvement District” to fund street repairs and infrastructure projects in the neighborhood surrounding the state Capitol, where government office buildings sit near empty storefronts.

Last year, with bipartisan support, the legislature added funds for policing in that district with an expansion of the state Capitol Police. Formerly a sleepy department patrolling state buildings, the force has significantly increased in officers since the middle of last year, and its shiny SUVs are a ubiquitous presence downtown.

Now, Republican leaders say more changes are needed, pointing to a significant backlog of criminal cases in the county courts, which leave some defendants waiting months or longer for trials.

The House version of the controversial bill, known as HB 1020, would expand the Capitol Complex district to cover about a third of Jackson’s population, and create a new judicial district with state government-appointed judges who could hear cases in the district. The judges would be appointed by the state Supreme Court chief justice, and prosecutors would be appointed by the state Attorney General, both of whom are conservative White elected officials.

The newly expanded district would stretch from the museums and Capitol building downtown, to the northeast city limits of Jackson, encompassing much of the city’s business district as well as key institutions such as Jackson State University and the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

According to CNN’s analysis of US Census data and the bill text, about 55% of people living in the district are Black, compared with 83% of Jackson as a whole. The district includes most of the densest White neighborhoods in the city, which are also some of Jackson’s most affluent areas.

The proposed district “looks like a redlining map from the ’60s,” Johnson said, referring to the decades-old discriminatory practice of denying loans in minority neighborhoods.

Lamar, the bill’s sponsor, has framed the measure as a way to help Jackson by increasing security and addressing the court backlog.

“There are too few law enforcement officers, too few prosecutors, too few public defenders, and too few judges to effectively administer justice,” Lamar, who represents a rural community two and a half hours north of Jackson, wrote in a recent op-ed.

But local leaders argue that the legislature should increase the number of judges who are elected locally in Jackson’s Hinds County – not bring in appointed judges.

“If they’re really concerned about helping speed along how cases are handled, why not add additional elected judges, as we do in every other district in the state?” asked Winston Kidd, the county’s senior elected judge, in an interview last week.

The version of the bill approved by a Senate committee on Thursday responds to some of that criticism by dropping the expansion of the Capitol Complex district and the new court system. Instead, it would add five new temporary judges in Hinds County, appointed by the State Supreme Court chief justice. Those judges would be replaced by a single new locally elected judge starting in 2027.

But the amended bill would expand the Capitol Police jurisdiction citywide, instead of just in the Capitol district. Any dispute over policing between the state-run department and the city-run Jackson Police Department would be resolved in favor of the state, according to the bill – unless the two departments sign a memorandum of understanding by July, which the mayor has declared he will not do.

Assuming the amended bill passes the full Senate, the two legislative houses would have to iron out the differences in a conference committee in the coming weeks.

A coalition of activists and faith leaders have organized against the bill, holding rallies on the Capitol steps and at churches around the city, and are planning to fight it out in court if it becomes law.

Supporters say the bill is on solid legal ground because the new court in the House version would be under the supervision of the elected judges, and the court’s decisions could be appealed to them.

But Jarvis Dortch, the executive director of the ACLU of Mississippi, argued that proposal would violate the state constitution by diluting the authority of elected judges, and go against Voting Rights Act provisions protecting representation for minority groups.

“You’re going to have a city within a city where Black folks are going to be second-class citizens and have no say over their policing or their judicial system,” Dortch said. “It’s blatantly unconstitutional.”

Concerns over expanding state-run police force

Some locals say they’re also concerned about how both versions of the bill would lead to a dramatic expansion in the jurisdiction of the state-run Capitol Police.

Since the department expanded last summer, some residents have complained of officers unnecessarily escalating interactions with suspects – especially in a series of high-speed car chases around the city that have left civilians injured or ended in shootings. In the span of three months last year, officers shot at least five people, one fatally, according to local news reports.

On September 25, Capitol Police officers fatally shot 25-year-old Jaylen Lewis, a father of two. In a heavily redacted incident report obtained by CNN through a public records request, officers reported that before the shooting, they saw Lewis run a red light and tried to conduct a traffic stop.

The department says that the shooting is still under review by the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, and it can’t release more details until that investigation is complete. The other four incidents were also reportedly investigated by the MBI, but the department didn’t respond to a request seeking details about them.

Arkela Lewis, Lewis’ mother, said she hadn’t received any explanation or a phone call from any state official, leaving her family outraged. If the Capitol Police territory is expanded, “it’s going to be a horrible thing for the city of Jackson, for people of color in Jackson,” she said in an interview.

According to the redacted report, the officers who shot Lewis were part of the department’s “Flex Unit,” a plainclothes street crime unit that drives unmarked cars. Capitol Police Chief Bo Luckey told a local paper last year that the purpose of the unit was “having boots on the ground and proactively policing.”

But critics say the plainclothes unit’s aggressive tactics make it similar to the notorious Scorpion Unit of the Memphis Police Department, which was disbanded last month amid national anger over the beating death of Tyre Nichols.

A friend of Lewis’ who was in the car with him during the shooting told the family that they had realized they were being followed but didn’t realize the car behind them was a police vehicle, Arkela Lewis and her daughter Alexus Lewis said.

The string of shootings has sapped support for Capitol Police in Jackson’s Black community – even among some residents who say that, in general, they’d like to see a stronger police presence in their neighborhoods.

In December, a Capitol Police traffic stop of a stolen vehicle led to a high-speed chase across the city that ended in gunshots. A bullet punched through the wall of Latasha Smith’s apartment in northwest Jackson, sailed over her 13-year-old daughter asleep in bed, and then hit Smith in the arm as she slept. Two bullet holes still adorn Smith’s wall – and a bullet remains in her forearm.

A brief statement by the Capitol Police at the time said that an “officer-involved shooting” had taken place that night and “shots were fired” next to Smith’s apartment. The department said that the MBI would investigate the shooting, but has not released further details.

Smith, who lives a few blocks from the home where civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated six decades ago, believes Capitol Police officers shot the bullet that hit her. That night, after she ran outside shouting “I’ve been shot,” she said she saw a Capitol Police officer holding a gun.

She said she wants her neighborhood to be safe, but that the department’s aggressive tactics run counter to that.

“Capitol Police are supposed to protect and serve, but who are going to protect us from them?” Smith asked in an interview. If the department’s jurisdiction is expanded citywide, she said, “I’m leaving – we Black folks can hang it up in Jackson then.”

The city-run Jackson Police Department has also faced allegations of excessive force in recent years, and has suffered from understaffing and long 911 response times. But residents say that at least the department is accountable to their local elected officials – unlike the state-run Capitol Police.

More broadly, there’s a significant divide in how some White and Black residents of Jackson see the Capitol Police. Johnson, the University of Mississippi professor, said many of his White friends viewed the department as “a much-welcomed presence, an answer to a pressing problem, that they wish everyone in Jackson could have.” But some Black friends, he said, have told him they were “scared to death for their Black sons to even drive through” the department’s jurisdiction.

Dwayne Pickett, a local pastor at a Black church, said he’s had parishioners call him and ask him to stay on the line with them when they see a Capitol Police cruiser pull up behind them on the road.

“There’s enormous amounts of fear in the community,” he said.

A spokesperson for the Capitol Police did not respond to requests for comment about the criticism. At a community meeting shortly after Lewis’ shooting, state Public Safety Commissioner Sean Tindell, who oversees the department, said that “anytime there is a loss of life, it’s tragic,” but defended the Capitol Police’s practices as “doing policing the way it’s supposed to be done.”

Power struggles pitting legislatures against city halls

In Jackson, the fight over the criminal justice system is the latest power struggle between the city and state governments in recent years.

The city, which has experienced a water quality crisis that has forced residents to rely on neighborhood distributions of bottled water, received about $800 million in federal funding for water infrastructure upgrades, most from a spending bill that passed Congress last year.

But another bill currently being debated in the state legislature would create a new regional board to take control of Jackson’s water and sewer system, with a majority of board members being appointed by the governor and lieutenant governor. That has raised the alarm of the federal monitor appointed to oversee the system.

Meanwhile, around the country, similar power struggles have been taking place between GOP-dominated state legislatures and Democratic big city governments in recent years, both over public safety and other issues.

In Missouri, a new bill would let the governor strip locally elected prosecutors of the power to handle violent crime cases. The move comes as the state attorney general is trying to oust the Democratic St. Louis prosecutor from office over allegations of neglect, which she denies.

In North Carolina, GOP legislative leaders have signaled that they may block Charlotte, the state’s largest city, from issuing a sales tax that would pay for a major expansion of its public transit system. The state house speaker has called the plan impractical.

And in Tennessee, the state legislature is moving forward with bills that would effectively cut Nashville’s city council in half and take state control over the city’s airport and stadiums – after the city council killed a bid for the 2024 GOP convention.

At the same time, local leaders in conservative corners of blue states have also clashed with their state governments – from California sheriffs who refused to enforce mask mandates during the pandemic to New Mexico’s Democratic attorney general suing local towns that have passed restrictions on abortion.

While tension between city halls and state capitols has long been a fixture of American government, experts say the fights are becoming more frequent – and more high-stakes – as the nation’s politics become more polarized and acrimonious.

One 2021 study found that GOP legislators were more likely than their Democratic colleagues to vote for proposals to limit local governments’ authority, and that those efforts were most common over “hot button” issues like guns and LGBTQ rights.

In some cases, rural legislators target liberal cities as “a way to score political points” and “pour a little more gas on the culture wars,” said Keith Boeckelman, a political science professor at Western Illinois University, who co-authored the paper.

In Jackson, some locals say that the bad blood over the criminal justice bill will remain even if the farthest-reaching proposals don’t make it through the legislative process in the coming weeks.

After she finished leading chants of “kill the bills!” at the church rally last week, Holmes, the activist in the “JACKSON VS. EVERYBODY” shirt, sat in the front pew and took stock of the situation.

“It feels like some of our leaders want a piece of Jackson for themselves,” she said. “So, it’s very important that we continue to say that Jackson is not for the taking.”