Uvalde school police chief Pedro “Pete” Arredondo told investigators he was more concerned about saving students in other classrooms than trying to stop a gunman who had already shot children and teachers.

An interview with investigators the day after the May 2022 massacre at Robb Elementary shows Arredondo talking bluntly about his recollection of events. CNN obtained a video recording of the previously unreported interview, where some of Arredondo’s answers conflict with his limited public statements.

It was the only meeting about his role that he had with the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS). He stopped cooperating with the DPS inquiry after its director labeled him as incident commander and blamed him for decisions that left dead, dying and traumatized children with a gunman for over an hour while officers waited in the hallway outside.

The critical moment in his decision making, Arredondo said, was when he saw children in other classrooms.

“Once I realized that was going on, my first thought is that we need to vacate. We have him contained – and I know this is horrible and I know it’s [what] our training tells us to do but – we have him contained, there’s probably going to be some deceased in there, but we don’t need any more from out here,” Arredondo said.

His decision to treat the gunman as a barricaded subject and not confront him effectively left all the students and teachers in Classrooms 111 and 112 for dead. It was one of many times he did not follow the training and protocol for an active shooter.

Arredondo stuck with that choice for over an hour, even when he thought he heard the gunman reloading and after it was confirmed children were trapped – injured and alive as well as dead – with the shooter.

CNN tried to reach Arredondo for this story. His attorney George Hyde said he was not authorized to respond to media requests. “I have informed him of your request and it will be up to him from there,” Hyde wrote in an email.

Arredondo has not contacted CNN. A previous phone number for him has been disconnected.

CNN has also informed the families of the victims about this reporting on Arredondo’s interview. Relatives have complained repeatedly that the only way they have been getting information is through CNN’s work.

‘I need a lot of firepower’

Arredondo, chief of the tiny police force for the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District, was one of the first officers to reach Robb Elementary, minutes after a gunman went through an unlocked door into the building last May 24.

He told investigators he heard shots being fired as he ran to the school and saw bullet casings still rolling on the floor as he entered. He described a hallway full of smoke from gunfire and saw Lt. Javier Martinez of the Uvalde Police Department retreat after he was shot at through a classroom door.

Arredondo, who had dropped his school and police radios when he got out of his car, called 911 to give them an update. The call was recorded at 11:40 a.m., seven minutes after the shooter walked into the school. CNN has obtained the full audio of the call, which was previously read out by DPS director Col. Steven McCraw.

“It’s an emergency right now,” Arredondo told the dispatcher. “I’m inside the building with this man. He has an AR-15. He shot a whole bunch of times … He’s in one room. I need a lot of firepower, I need this building surrounded, surrounded with as many AR-15s as possible.”

Arredondo confirmed to investigators that he only had his handgun and wanted rifles. That is one of the many times Arredondo’s decisions go against active shooter training and protocols.

Records supplied to CNN by DPS show Arredondo took required active shooter training at least three times, including in the December before the massacre. The specific course he took then instructs officers to “isolate, distract and neutralize” the attacker. It reminds officers “First responders to the active shooter scene will usually be required to place themselves in harm’s way and display uncommon acts of courage to save the innocent.”

Even as Arredondo was calling for assault rifles, it is now known that there were officers with long guns at Robb by 11:40 a.m., at the other end of the hallway. Without a radio, Arredondo’s contact with the other group of officers was by phone, calling a colleague from another force he knew well, he said.

Arredondo also said he ignored his phone once “everybody in the world” started calling. He gave the 911 operator specific instructions, according to the recording. “Call me when SWAT is set up. I’m going to have you on vibrate though, so call me twice if you have to,” he said.

‘Time’s on our side right now’

Arredondo, who was fired as school police chief in August, has said that he never considered himself to be the incident commander. He declined to speak to CNN multiple times in the days after the massacre, including outside his office on June 1 after he had been blamed as the officer in charge whose catastrophically wrong assessments caused the failed response.

In his only extensive public comments since then, he told The Texas Tribune: “I didn’t issue any orders … I called for assistance and asked for an extraction tool to open the door.”

Arredondo’s interview with investigators less than 24 hours after the tragedy and footage from surveillance and body cameras show he gave plenty of direction.

He described getting officers into a “pyramid” formation, all on the same side of the hallway, to avoid crossfire if the gunman came out of the door.

And when he tried the handle of the door to another classroom and found it unlocked with students and a teacher inside, he made the critical decision to save others first.

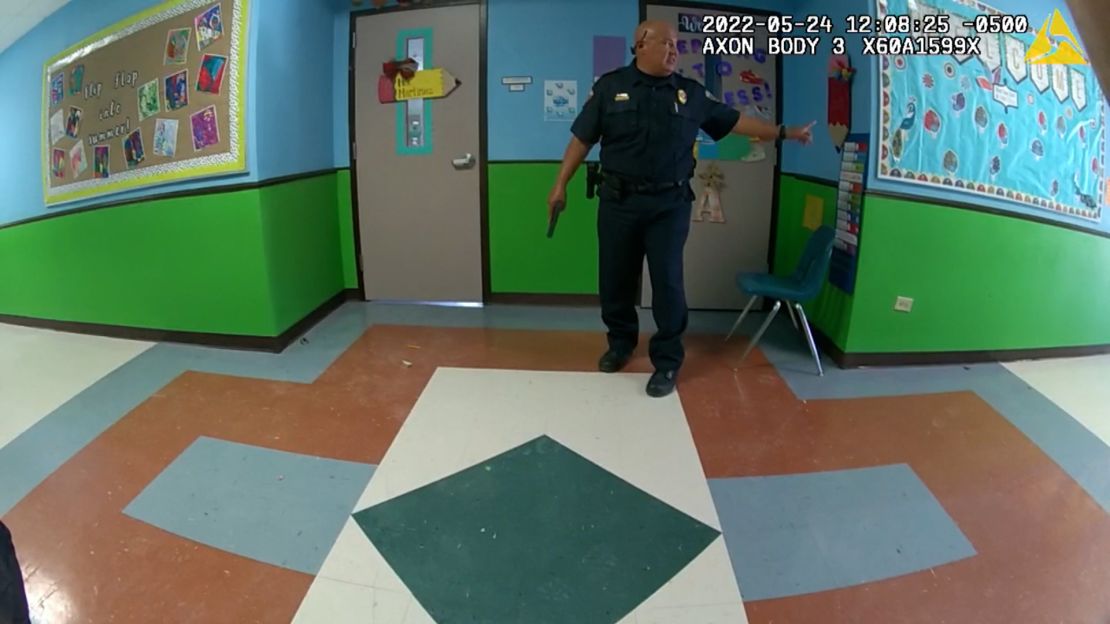

“We’re going to clear out this building before we do any breach,” Arredondo told officers in the hallway at about 12:08 p.m., as heard on body camera footage. “As soon as they clear this room, I’m going to verify what’s been vacated, guys, before we do any kind of breaching.”

He went on: “Time’s on our side right now. I know we probably have kids in there, but we’ve got to save the lives of the other ones.”

Again, active shooter training for law enforcement states the opposite. Since the 1999 Columbine school shooting when local police waited outside for SWAT teams, the emphasis has been on speed – for any officer to go at once to the sound of gunfire and stop the shooter.

Nineteen children and two teachers were killed in the Uvalde massacre, and more injured. At least three of the dead – two children and one teacher – were still alive throughout the 77-minute siege. Other students and teacher Arnulfo Reyes were injured and waiting for help. One of them, 4th grader Mayah Zamora, needed more than 20 surgeries and spent two months in hospital after she was rescued.

‘I heard him reload’

In the hallway, body camera footage shows that Arredondo called for master keys, but at least initially the intention was to open up the nearby classrooms and get people further into safety, not to go to where the gunman was.

“Are we getting the master key?” he asked in a phone call, his side of which was captured on body camera. “I need to verify that this west wing is completely vacant.”

Arredondo continued with that plan even as police radios blared at about 12:12 p.m. with news that a child was calling from a “room full of victims.” It did not change after a volley of shots from the classroom at 12:21 p.m. He tried to talk with the shooter, in another contravention of active shooter policy. The gunman never responded. Instead, Arredondo told investigators: “I’m certain I heard him reload.”

Throughout the response, Arredondo said he did not know that Classrooms 111 and 112 had an interior connecting door. He told investigators he believed the hallway door was locked but he never tried to open it.

The doors and locks were a focus of his interview with officers from the DPS and FBI. He told them he regularly found classroom doors unlocked when he did his rounds, and indeed he opened at least one other door to help to evacuate students that day. But still, he thought he would not be able to get inside the rooms where the shooter was.

“I know that I wasn’t going to be able to grab that door. That’s my thought,” he said. Yet in June, he told The Texas Tribune he and a police officer tried the doors to 111 and 112 and both were found to be locked. There is no evidence that that happened. McCraw testified to a Texas Senate hearing in June that no one touched the doors before the classrooms were stormed and he did not believe that they were ever locked.

‘I wasn’t aware of what was going on outside’

When he saw men he assumed were Border Patrol officers arrive at the other end of the hallway, Arredondo said he believed they were there to force entry to where the gunman was holed up.

“I did let them know we’re taking these kids out first. We need to preserve the life of everybody around him first,” he told investigators.

The chief said he requested a sniper and told officers outside to make sure the shooter did not escape through the roof. But he did not know what was happening away from where he was.

“We’re right in there, I wasn’t aware of what was going on outside,” he said.

Outside was leaderless chaos.

Exclusive CNN reporting has shown:

- The city’s acting police chief knew there were children trapped with the gunman but did not organize a rescue;

- The county sheriff stayed initially at a different crime scene and had vital information about the shooter that was not shared;

- A Texas Ranger told investigators his actions at the scene were “minimal” despite being part of the elite force that is required to help local agencies stop crime and violence; and

- A captain with the state Department of Public Safety issued an order to halt the entry into the classroom that unknown to him was already happening, because he thought a more skilled team was on the way.

Arredondo was never asked about who had command of the response during his nearly one-hour interview with investigators. That became a key issue in the changing narrative from state officials as the story morphed from a heroic law enforcement response lauded by Gov. Greg Abbott the day after, to an “abject failure,” as labeled by DPS director McCraw in June.

“The only thing stopping a hallway of dedicated officers from entering Room 111 and 112 was the on-scene commander who decided to place the lives of officers before the lives of children,” McCraw testified before a special Texas Senate committee.

In the interview, the investigators were respectful and understanding to Arredondo, who was loquacious and sometimes jovial in return, saying how he was planning to rib a colleague who had not managed to run past him in the initial approach to the classrooms.

“We’re going to get scrutinized, I’m expecting that. We’re getting scrutinized for why we didn’t go in there,” Arredondo said, before giving his reasoning again.

“I know what the firepower [the shooter] had, based on what shells I saw, the holes in the wall in the room next to his. I also know I had students that were around there that weren’t in the immediate threat besides the ones I know were in the immediate threat and the preservation of life around, everything around him, I felt was priority,” he explained. “Because I know there’s probably victims in there and with the shots I heard, I know there’s probably somebody who’s going to be deceased. I know these weren’t,” he said of the people in the classrooms without the gunman.

Asked what advice he would give to the next department to have to deal with a school shooter, he identified three critical areas, all of which are now known to have had flaws in Uvalde.

“Never minimize your training, never minimize your equipment, and never minimize your communication.”