Uvalde’s acting police chief knew there were “eight to nine” children alive and needing rescue from a shooter in the classrooms at Robb Elementary but failed to organize help, new audio of a phone call and CNN analysis of newly obtained video shows.

Lt. Mariano Pargas called his Uvalde Police Department dispatchers to get details after they relayed a call over the police radio from 10-year-old Khloie Torres that she was in a room “full of victims,” according to a recorded conversation obtained by CNN from sources close to the investigation into the failed law enforcement response to the massacre.

Communication failures and a lack of leadership in the chaotic response are blamed for why it took 77 minutes to stop the gunman who holed up in two conjoining classrooms, with some officers saying they were not made aware of the 911 calls from children and others saying they could not hear radio transmissions.

Pargas’s phone call proves for the first time that a senior officer was directly made aware of a 911 call from inside the classroom and was given details on the exact location of children who were alive and begging to be rescued.

The conversation, recorded routinely as part of police procedure, shows Pargas calling at 12:16 p.m., about six minutes after Khloie reached 911 and when she was still on the line with a dispatcher, and four minutes after the call information was relayed on the Uvalde police radio channel.

“The calls you got in from the … from one of the students, what did they say?” he asks.

The dispatcher responds: “OK, Khloie’s going to be, it’s Khloie. She’s in Room 112, Mariano, 112.”

Pargas asks: “So how many are still alive?” and is told: “Eight to nine are still alive. She’s not too sure … She’s not too sure how many are actually DOA or possibly injured. We’re trying …”

Pargas ends the call with “OK, OK thanks” and disconnects.

Based on analysis of surveillance and body cameras at the scene, he walks back into the hallway at 12:17 p.m. and mentions injured victims to a Border Patrol officer. At 12:18 p.m., he does not mention the children when a Texas Ranger talks to him about organizing the flow of information.

Pargas is last observed walking away from the school’s entrance at 12:20 p.m. New angles of the hallway security cameras obtained by CNN confirm Pargas does not reenter the hallway near room 112 where officers are gathering and eventually breach the classroom door some 30 minutes later.

Officers entered the classrooms and killed the shooter at 12:50 p.m., 77 minutes after he began his murderous rampage inside the school. Nineteen children and two teachers died after the attack in Uvalde, Texas, last May 24. At least three of the dead – two children and one teacher – survived their initial injuries and died after the classrooms were breached.

Pargas was placed on administrative leave by Uvalde Mayor Don McLaughlin in July when videos from body cameras raised questions about whether he had taken any action to assume command. “This administrative leave is to investigate whether Lt. Pargas was responsible for taking command on May 24th, what specific actions Lt. Pargas took to establish that command, and whether it was even feasible given all the agencies involved and other possible policy violations,” McLaughlin said in a statement at the time.

The recording of the phone call newly obtained by CNN only seems to underscore Pargas’s inaction.

When CNN reached Pargas by phone seeking comment for this story, he said he was unable to talk about anything to do with the police department on the advice of his lawyers.

“I want to defend myself. I really do,” he said on Monday. “There’s a lot of stuff that I can explain, that I would love to defend myself. And that’s the problem we’re having right now … the victims and everybody’s saying everything they want to say, but we can’t say nothing because we were told not to talk to, you know, we can’t say anything cause we’re still under that, not to talk to any, media or anything.”

He added: “It’s not that we’re afraid because there’s nothing to be afraid of. We did what we could, but the thing is that we’ve been told that we can’t (speak publicly).”

Just last week, Pargas was reelected as a Uvalde county commissioner after defeating three write-in candidates including Javier Cazares, who lost his daughter Jackie in the shooting.

Clear details and no action

The audio of the 911 calls from Khloie Torres and her classmate Miah Cerrillo, published exclusively by CNN with the approval of the girls’ parents, revealed the girls gave details and directions to the authorities at 12:10 p.m., more than 30 minutes after officers started arriving en masse at the school but still a full 40 minutes before forces entered the room to challenge and kill the shooter. Later in the call, after gunshots are heard, Miah says of the killer, “He’s shooting.”

Recounting what happened in an interview with a Texas Ranger and an FBI agent two days after the shooting, Pargas makes no mention of being aware at the time that children were with the shooter in the conjoining classrooms of 111 and 112, or of the 911 call, according to records of interviews obtained by CNN.

But he did know that teacher Eva Mireles had been shot in her classroom as he was told by her husband, a former member of Pargas’s police department then working for the school police, Pargas said. He said he observed the officer, Ruben Ruiz, tensing, and decided he should be disarmed and taken out of the hallway.

“He was holding the gun real tight,” Pargas said of Ruiz in his interview. “And we were just afraid that he was gonna try to run in the classroom and try to do what I wanted to do if I could have done it.”

In a second interview in mid-June, when prompted about 911 calls from inside the classroom, Pargas said he did not have a clear memory. “I don’t remember. I really don’t,” he said. “I know somebody said, and I’m not sure if it was dispatch or somebody, I remember somebody saying that they thought there was a kid calling and calling dispatch that he was inside.”

Asked if he relayed that information, he replied: “I’m almost sure I did to the people that were lined up (in the hallway).”

Pargas did not mention his follow-up call with his department and said he did not know for sure there were children in the rooms with the gunman.

“We didn’t know who or what was in there because he was so quiet,” he told a Ranger. “We had no idea.”

Later in the interview, he added: “The last thing we thought was that he had actually shot the kids. We thought he had shot up in the air, broken the lights. We had no idea what was behind those doors.”

Why the chief didn’t take charge

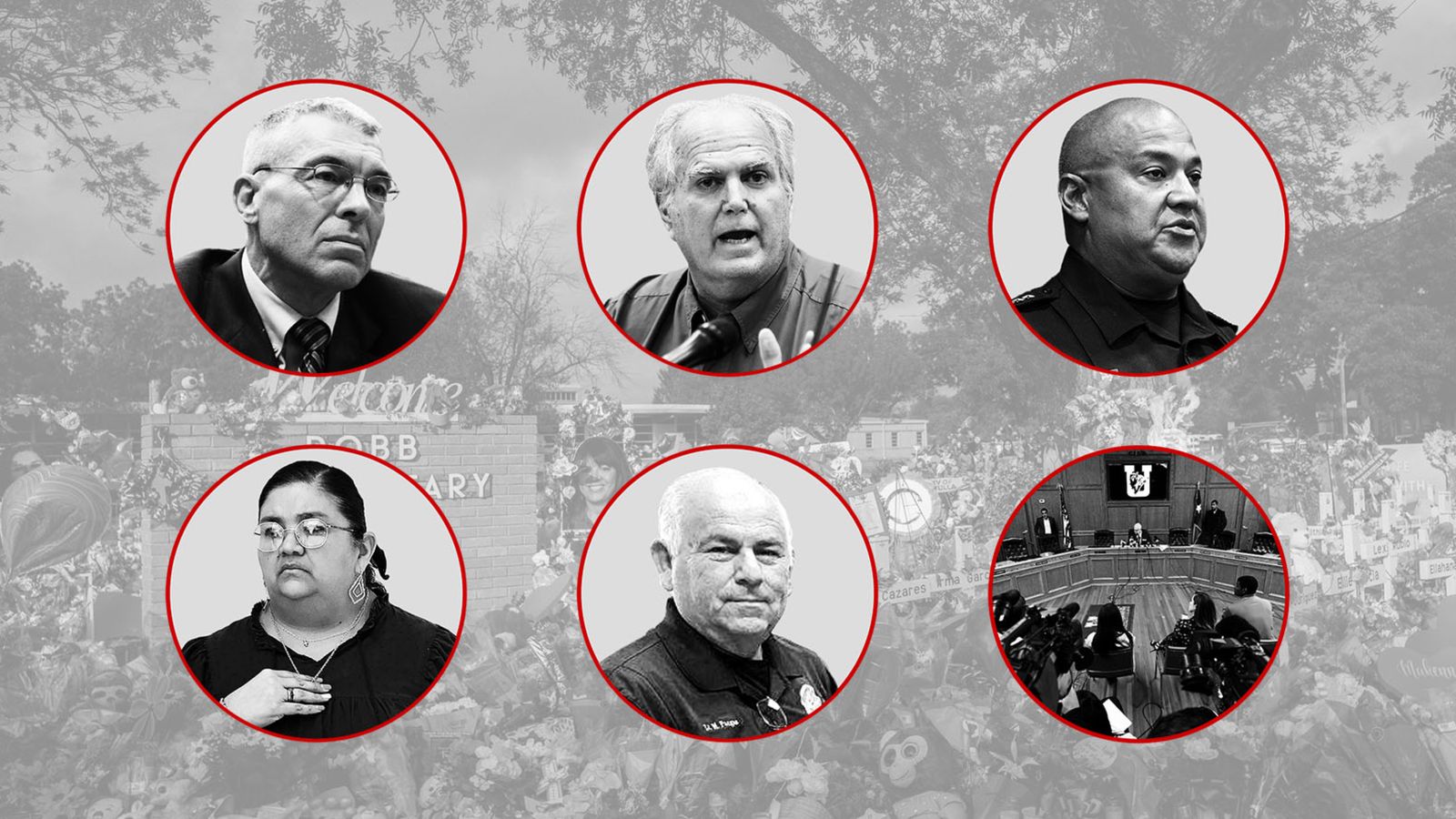

Pargas was acting chief of the Uvalde Police Department on the day of the massacre, while Chief Daniel Rodriguez was on vacation.

He told investigators he rushed to the vicinity of the school – about a mile and a half away – when someone came into his office to say there had been an accident and there was a man with a rifle.

CNN analysis of video from surveillance and body cameras shows Pargas was the fifth officer to run into the school hallway after the gunman.

Three of Pargas’s UPD officers were shot at as they approached the classrooms where the gunman had holed up, and two were injured.

But Pargas said he did not consider who should be in charge, especially once he saw then-school police chief Pedro “Pete” Arredondo.

“The minute I saw Pete Arredondo … I figured this is school property and we’re here to assist pretty much. That’s normally what we do – when something happens in the school, we pretty much assist the school because it’s their jurisdiction,” Pargas told the Ranger gathering information in mid-June.

“I don’t think I stopped to say, well, who’s giving orders or who’s in command. We’re just trying to see what we could do as fast as we could.”

Arredondo has said he never considered himself the incident commander, though he did try to negotiate with the shooter as well as issue orders to those in the hallway with him.

More officers from more local, state, and federal agencies arrived, and there was no clear direction of what was going on inside or outside the school building.

As they stood at the entrance door at 12:10 p.m., guns drawn but static, a UPD detective asks Pargas about the Border Patrol tactical team: “Are we just waiting for BORTAC, or what’s going on?”

Pargas responds: “Yeah, they tell me the DPS Ranger found somebody and they’re going to come in.”

Another local officer then asks him for an “OIC” – an officer in charge – and Pargas appears to direct him to Texas Ranger Christopher Ryan Kindell, who is himself now suspended and under investigation for actions he failed to take at Robb Elementary.

Pargas’s thoughts on whether to take charge did not appear to change as time went by and more information came out.

A Texas House committee report into the tragedy at Robb Elementary said the lack of any effective incident command was a key problem. The report, which faults the choices Pargas made, said the fact that UPD officers responding to reports of a crash and a man with a gun were first on scene would have made them initial commanders, and while Arredondo could then have assumed command at the school he would have needed to go outside the building to coordinate effectively.

Pargas had arrived at the school where his granddaughter was a student without a radio and may not have heard the transmission about Khloie’s call.

But one of his detectives made sure he was aware of what was said.

“Full of victims, child called 911 saying the room’s full of victims,” he is told at 12:12 p.m., as seen on footage from a body camera worn by another officer.

“The room is full of victims,” the detective reiterates as Pargas pulls the radio from the detective’s vest. “Child 911, child 911 call.”

Pargas then walks inside the school building where officers from local, state and federal law enforcement agencies were lined up at the end of a hallway leading to the classrooms.

“A child just called that they have victims in there,” he says before turning and leaving the area.

Two days after the massacre, Pargas told an investigator he wished more could have been done.

But then he gives some praise to the operation: “I think keeping him contained, I think it did save a lot more lives that could have been taken that day.”