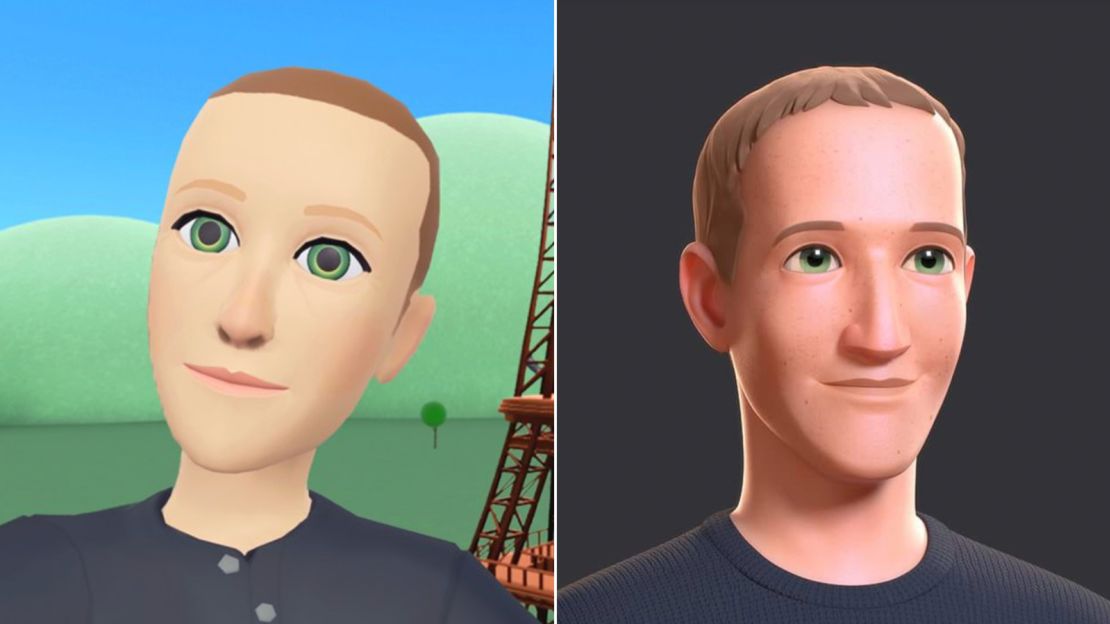

Mark Zuckerberg has bet his company’s future on an ambitious long-term vision of people carrying out greater portions of their lives in virtual spaces through digital alter egos. But an image Zuckerberg recently posted to his Facebook page served as a reality check of sorts for virtual reality, at least in its current form.

The image, which was also included in a company blog post, showed his blocky, cartoon-like avatar in Facebook-parent Meta’s flagship social app, Horizon Worlds, staring out into the distance with enormous, vacant-looking eyes and a tight-lipped smile. In the background, plopped onto a field of green grass, were simple-looking models of the Eiffel Tower in Paris and the Sagrada Familia cathedral in Barcelona, to mark the launch of Horizon Worlds in France and Spain in mid-August.

The criticism online came swiftly. “Imagine spending billions on the metaverse and your avatar looks like this!” one Twitter user wrote. “Mark Zuckerberg invents The Sims!” another tweeted. Days later, Zuckerberg himself admitted the image was “pretty basic” and posted a screenshot of a more detailed version of his avatar, saying that “major updates” to Horizon and avatar graphics are “coming soon.” He promised to share more details at Connect, Meta’s annual conference focused on VR and augmented reality, which is held in the fall.

The episode is the just latest example of how difficult (and increasingly important) it is to create highly detailed VR avatars, even for a tech giant that has invested heavily in buying and building hardware and software. Having positioned itself as a leader in the small but growing VR market, Meta faces dueling challenges: Users have high expectations for what they should be able to look like in virtual spaces, but meeting them is, in many ways, difficult with today’s headsets.

VR avatars must look good (or at least good enough) and function reliably in real time and in apps that are typically running on untethered headsets like Meta’s Quest devices rather than on bulky but more powerful laptop or desktop computers. There are many other non-technical issues at play as well, including that different people have different expectations for how avatars should look and act in different situations. Should the avatars look like the VR user themselves, or someone else, or, say, a giant stick of butter?

“Avatars have been very hard to get done, even in the visual effects industry,” said Abhijeet Ghosh, the chief technology officer and chief scientist at London-based Lumirithmic, which uses tablets and smartphones to capture 3-D facial scans for a range of applications, including VR.

Meta did not respond to a request for an interview about the challenges of avatar creation. In an April episode of his monthly podcast, “Boz to The Future,” Meta CTO Andrew “Boz” Bosworth pointed out how vital avatars are across all kinds of digital experiences.

“They’re extremely critical to how people represent themselves in digital spaces, within the metaverse and beyond,” he said.

The technical challenges

Meta is not alone in the blocky simplicity of its VR avatars. Meta, Rec Room, and Microsoft’s AltSpaceVR, among others, have been working for years to improve the appearance of their avatars and make them increasingly customizable.

Those who mocked how Zuckerberg looked in Horizon Worlds were probably expecting much more realistic illustrations from a giant company such as Meta, given the realism of characters in popular video games like “Call of Duty” or “Gears of War,” Ghosh said. “But I guess people don’t understand the effort that goes into high-end visual effects,” he said, which in the video game realm can include a team of artists dedicated to modeling characters’ appearances.

At its most basic, untethered headsets like Meta’s Quest 2 still have a slew of technical limitations that make it hard for apps to offer extremely detailed VR avatars that can also respond in real time to the ways we move our faces and other body parts.

There can be limitations related to the power of the computer, graphics processor, and the amount of included RAM. Moreover, most people currently using VR don’t use extra sensors to track their entire bodies, so sensor-based tracking is limited to what’s built into the headset and any accompanying hand controllers. (This is also why avatars on some social apps, such as Horizon Worlds and Rec Room, exist only from the torso upwards.)

Essentially, today’s headsets can only render so many of the triangles that are used to make up 3-D images in VR, explained Timmu Tõke, CEO and cofounder of avatar creation platform Ready Player Me, which lets people create avatars that they can use across a range of games and apps such as VRChat. This means that if a social app wants to include high-definition avatars, it will only be able to support a handful of people in a scene.

Horizon Worlds currently suggests developers who build their own worlds limit them to eight to 12 users at a time. “More players will require more resources to render your world, and may add some limitations when building,” the company’s Horizon Worlds creation tutorial states.

“Creating an avatar that looks good and performs good — in a VR environment, especially — is extremely hard,” Tõke said.

Trying to bridge the uncanny valley

Meta is trying, however. Since 2019, the company has been working not just on building good-looking avatars, but full-body ones with photorealistic faces, which it thinks are key for feeling immersed when interacting with others in VR.

This effort matches what Guo Freeman, an assistant professor at Clemson University, found when researching what people want when it comes to VR avatars in social settings. She repeatedly heard that they want an avatar that is consistent with how they look in the non-digital world, she said.

“What is kind of different between social VR and other types of gaming and virtual worlds is people want to build an avatar that looks like them,” she said.

Creating a photorealistic VR avatar of the average headset wearer remains a monumental task, however. A person’s face and facial expressions must first be scanned to create a 3-D model of their head (or their entire body, to create an avatar that looks like them from head to toe), which can then be animated. This process currently tends to require a large rig of equipment, including cameras, lights, and computers.

Ghosh said Lumirithmic is working to make this simpler and more accessible by using off-the-shelf electronics like an arrangement of smartphones and tablets, but it’s still in the early stages. Eventually, he envisions people will be able to scan their own faces at home or at a mall, and use that for a VR avatar.

The more realistic-looking the avatar’s face, though, the more VR experts told CNN Business they worry about the issue of the Uncanny Valley, which is the disturbing feeling some people have in response to human-like representations that aren’t quite human.

“It’s just extremely hard to create a realistic avatar that crosses the Uncanny Valley,” Tõke said. “It just ends up looking creepy.”

And not everyone wants to want to look like themselves in VR, or even like a human. A quick visit to popular VR social app VRChat makes this clear: You might walk into a virtual bar and smack into a dinosaur, a chicken, or something else entirely. Cam Mullen, CEO and cofounder of Nevermet, a dating app that helps people get to know each other via their avatars, told CNN Business he likes to appear in VRChat as a jalapeno pepper.

“You can be an avatar that’s more masculine, more feminine; you can be a furry, you can be a flower. You get to express yourself freely,” he said. “And you can tell a lot about a person’s personality by the avatar they choose to embody.”