Soldiers toting guns and grenades while drunk, looting private property, and squabbling with fellow fighters to the point of armed stand-offs: Civilians who have escaped the Russian-controlled city of Kherson in Ukraine’s south say their home has become unrecognizable since Moscow’s troops began their uncompromising occupation in early March.

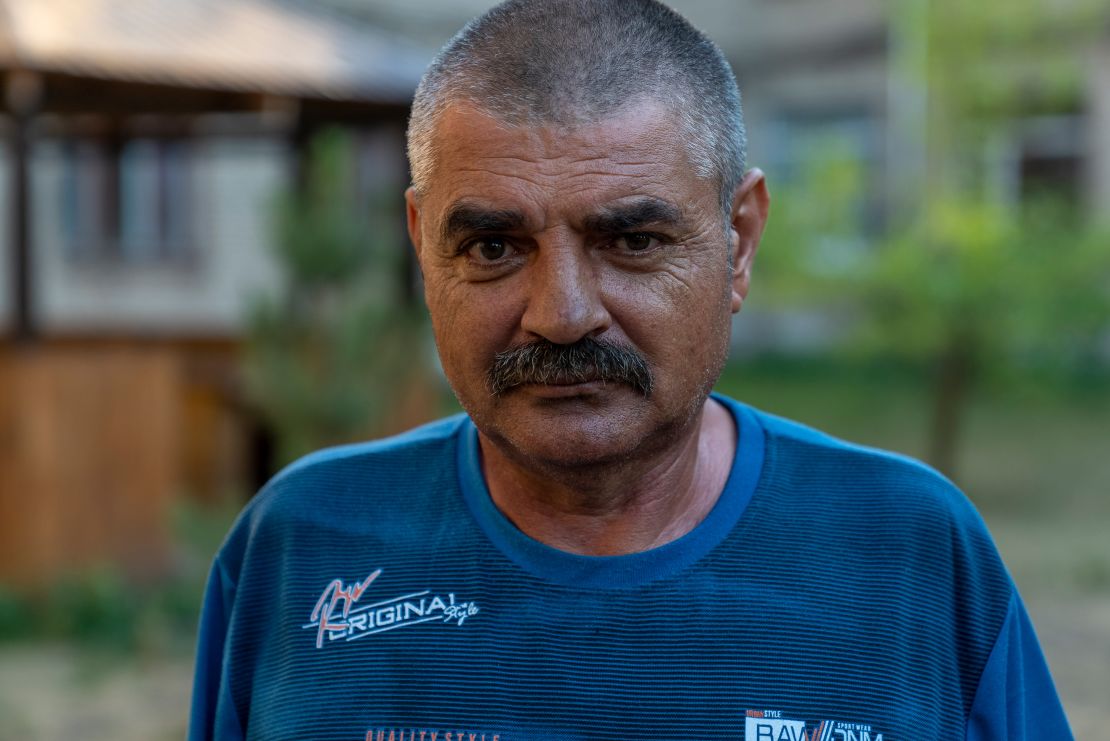

After four months living under Russian rule, farmer Andrei Halilyuk traveled on foot, by bus, car and a rubber dinghy over a river to get to the Ukrainian-held city of Kryvyi Rih. It took the grandfather 12 hours on roads sometimes littered with landmines.

He calls the invaders “barbarians.” “There is no other word for them,” he says, describing pro-Russian fighters from Donetsk squatting in apartments.

“How is it possible for children to be there if they’re walking around drunk with guns and grenades in the village. How can a child see this?” Halilyuk asks.

Ill-discipline among the mishmash of mercenaries, conscripts, separatists, and soldiers that Russia has relied on to attack Ukraine has contributed to the chaos of its occupation. Halilyuk says in his village, fighters for the Russia-friendly Donetsk People’s Republic turned on their Russian counterparts as they tried to steal a local man’s car. What resulted was a fierce argument at gunpoint, between two groups meant to be on the same side.

“They almost shot each other,” Haliluk recounts. “They were fighting among themselves. They cocked their guns at each other.”

“And they came to liberate us. From who? Did we ask for this? Did we ask for you to come here?”

Every day, around 400 people arrive in Kryvyi Rih from Russian-occupied territories and the conflict zone, grateful to reach the relative safety of the industrial city some 40 miles north of the frontline. In total, more than 61,000 have taken refuge there since Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24.

One local official in Kryvyi Rih told CNN that administrators began printing paperwork for displaced people on the day Russia invaded, predicting the mass exodus that would follow.

“I would wake up each morning to explosions and gunfire, then go to sleep at night with explosions and gunfire,” Halilyuk says. “Here it’s quiet. Yes, there are air raid sirens from time to time, but it’s not like you’re in bed shaking back and forth.”

Kherson resists

A Ukrainian fightback to the south has pushed Kryvyi Rih out of the range of Russian artillery, according to the local military administration. But nowhere in this country is safe from Russian missile attacks.

Now, Ukraine is hurling missiles of its own at Kherson – making use of donated military hardware such as the American HIMARS mobile rocket system to strike deep into enemy territory.

The Ukrainians say hits on Russian ammunition depots and command posts in Kherson have made it easier for them to take back villages, inching closer to civilians who they say are working to oust the Russians.

When Russian troops first took Kherson, locals met armored personnel carriers with protests – brandishing Ukraine’s blue-and-yellow flag.

Now, the occupation has cut off the city’s communications with the outside world, but the Ukrainian government claims there remains a local resistance movement. Anti-Russian graffiti and effigies of Russian troops remind the occupiers of its existence.

“People have an understanding that the liberation of the territory will happen, that the collaborators and occupants will not stay there forever,” said Nataliya Humeniuk, a spokeswoman for the Ukrainian military’s southern command.

“People do not want to work with them. They don’t want to teach their curriculum, they don’t want to treat their soldiers. They do not want to. This is resistance,” she says.

Forced to be Russian

Home to around 300,000 people before the war, Kherson is the largest population center Russia has captured in its five-month campaign. There, the newly installed regional administration has repeatedly said it will hold a referendum on becoming a “full-fledged” member of the Russian Federation.

The White House believes this effort by Russia to formally annex the Kherson region, as well as parts of Zaporizhzhia and the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, could happen before the end of this year. The Russian ruble would be established as the official currency and Ukrainians would be forced to apply for Russian citizenship, the White House said Tuesday.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov appeared to confirm such intentions on July 20, when he said Moscow’s geographical objectives now stretched beyond Donetsk and Luhansk to “Kherson Region, Zaporizhzhia Region and a number of other territories.”

In Kherson, the ruble is already in circulation and official forms are distributed in Russian – whether locals can speak the language or not.

Local endocrinologist Dr. Maksim Ovchar says he helped his Ukrainian-speaking neighbors by translating those forms, but he refused to work for the imposed administration.

“I lost my job. My house. Some of my friends I lost, they (were) murdered by the Russians,” he says.

The 26-year-old met CNN at a reception center for displaced people in Kryvyi Rih, where he broke down in tears, admitting he was embarrassed to be turning to charity. But Moscow was a master he would not serve.

“They wanted to co-opt me,” he says, “make me a member of the occupation administration in public health. I was the last endocrinologist in the city and probably in the region. Because everyone fled.”

Dr. Ovchar says he was detained twice for his recalcitrance, with armed Russians ultimately threatening his family before he fled Kherson with his grandmother. Ovchar chose July 7 to travel, when, he says, Russian troops were drunkenly celebrating the anniversary of an older military victory in Luhansk, eastern Ukraine.

Blocking escape

Many major routes out of Kherson have been closed off by the Russian army. In the frontline town of Zelenodolsk, an hour’s drive south from Kryvyi Rih, hundreds of discarded bicycles tell of improvised escapes.

Recent drone footage captured by a Ukrainian soldier shows a bedraggled column of women, children and the elderly walking a dusty road to safety. Cars have been shot at on other roads, escapees say. The town was shelled by the Russians on multiple days this week.

At the Kryvyi Rih reception center, Dr. Ovchar’s face contorts with tears and anger as he admits that his hatred of Russia’s war has led him to question his own Hippocratic Oath.

Ukrainian doctors treated wounded Russian soldiers when they arrived at his hospital after a fight with the local resistance. Now, he says, he’d kill them if he had the chance.

“Despite the fear and me being a doctor, I can’t allow myself to do harm a person, but I’ll tell you honestly if there was a Russian I would kill him if I had a gun.”