The pandemic shone a spotlight on the vast disparities in benefits and rights among America’s workforce and helped fuel a movement to unionize more workers.

And with today’s tight labor market, workers continue tohave the upper hand — there are almost twojobopenings for every unemployed person — creating an environment that’s even more favorable to labor union activity.

In the last year, unions have been formed at big corporations such as Starbucks, Amazon, and Alphabet; union election petitions filed with the National Labor Relations Board from October 2021 through March 2022 were up 57% from the same period a year before; and a September Gallup poll found that 68% of Americans surveyed were in favor of labor unions – the highest level of approval since 1965.

But as the war in Ukraine, record gas prices and spiraling inflation continue to put pressure on the US economy, what remains to be seen is whether the newly robust labor movement could weather higher unemployment and an eventual economic downturn.

The extraordinary conditions that created this more pro-worker market won’t last forever, said Heidi Shierholz, president of the Economic Policy Institute and former chief economist for the US Department of Labor under President Barack Obama.

“To the extent that has contributed to this increase in workers organizing … that will abate,” she said. “But how much momentum will have been established before that time, it’s not going to be zero.”

“This daily drumbeat of seeing workers win when they’re trying to organize, that’s not going to be quickly unlearned,” she added.

In April, workers at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island were the first to vote to successfully unionize in the company’s history; what began as a slow drip of unionizing Starbucks stores now totals more than 100 locations; employees at Apple stores in Georgia and New Yorkand, just last week, a Massachusetts Trader Joe’s,are trying to do the same, citing concerns related to health and safety, pay, benefits, hours and working conditions.

Noel Bennett is a shift supervisor at a Starbucks in Santa Cruz, California, that voted to unionize last month. For workers at her store, it came down to a simple desire: To have their voices heard.

“I think, especially due to the pandemic and seeing how corporations might not really think about the worker and workers’ experiences, I think that’s what really made partners at Starbucks realize that what’s happening could be better, and that unionization can be that thing that allows us to have a voice and to obtain the ability to live in this economy,” she told CNN Business.

The latest batch of unionization efforts are still likely heavily influenced by pandemic-related issues and demands placed on workers, but the current economic state is layering in other factors, said Ileen DeVault, professor of labor history at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

“I think many of these efforts at unionization are still concerned about workers’ treatment in the workplace, whether that’s health and safety issues or hours of work or expectations about how much work is going to be accomplished,” she said. “I do think that inflation and, in particular, the ridiculous rise in gas prices is also really on workers’ minds.”

But the current economy also benefits workers, DeVault said, adding that it’s easier to risk one’s job when there are plenty of other positions available.

Also contributing to a potentially favorable environment are actions taken by the Biden Administration, which has explicitly promoted pro-union measures, including creating the White House Task Force on Worker Organizing and Empowerment, which in February released nearly 70 recommendations for action; tapping former union leaders and lawyers to fill key roles such as Secretary of Labor and general counsel for the National Labor Relations Board; and backing the Protecting the Right to Organize Act of 2019, which is stalled in the Senate after passing the House of Representatives last year.

Yet despite the tight labor market and Biden’s efforts, union membership is not as common as itonce was.

In 2021, 14 million workers belonged to a union, the lowest number since 1983, when comparable data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics was available.

And from the perspective of the business community, an increase in petitions and one-off unionization votes does not necessarily make a movement.

“These campaigns tend to be very site-specific,” said Glenn Spencer, senior vice president of the US Chamber of Commerce’s employment policy division. Spencer noted while workers at one Amazon facility in New York voted to unionize, workers at another site there opted not to. “And I think if you look at even the individual Starbucks that are organizing, it’s 100 stores out of 17,000, so there’s not this broad movement sweeping through the company.”

Spencer said the Chamber is paying particular attention to developments at the NLRB and other federal agencies.

“We need to be very mindful of the regulatory framework that employers are operating under, so if there are changes to the rules that we can’t prevent, then we just need to make sure that employers know how to adapt to that new reality,” he said.

The actions in recent months, albeit relatively small, could have an outsized influence on efforts to come, DeVault said in an interview with CNN Business.

“Those are being talked about in newspapers and TV stories and radio stationsacross the country,” she said. “And so it means that the idea of forming a union is suddenly available to almost every American.”

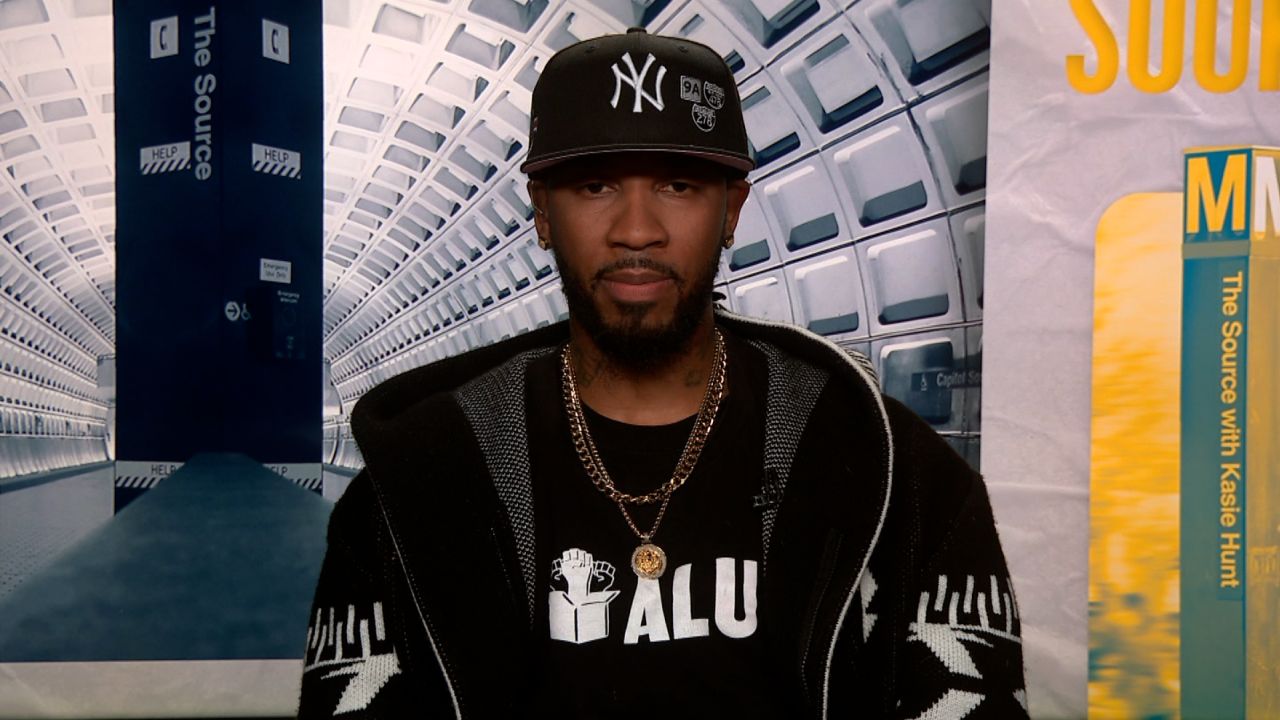

TristianMartinez, an organizer for the Amazon Labor Union, told Delyanne Barros, host of CNN Audio’s Diversifying podcast, he hopes that to be the case.

“We did it; we took on one of the richest companies in the world and we won,” Martinez said on Diversifying’s latest episode. “I hope and pray that there will be just a mountain of other dominoes falling everywhere. I only see it getting bigger and bigger.”