Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

A strange early relative of the giraffe was perfectly adapted for some serious headbutting 17 million years ago, according to new research.

The oddball giraffoid didn’t have the signature long neck of today’s giraffe. Instead, the ancient animal, built for fierce fighting, sported helmet-like headgear and the most complex head-neck joints ever seen in a mammal.

Researchers have dubbed this creature Discokeryx xiezhi. In Chinese legends, xiezhi is a mythical one-horned creature resembling a goat.

The fossil was first found in China’s northwestern Junggar Basin in 1996, and researchers have been studying it at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing ever since. Since then, more fossils have been recovered.

At first, scientists weren’t really sure what they were looking at as they studied the unusual skull and four cervical vertebrae. It was only within the last three years that researchers realized this weird fossil belonged to a giraffoid – and that it might help them unlock how giraffes have evolved.

Evolution of an oddball

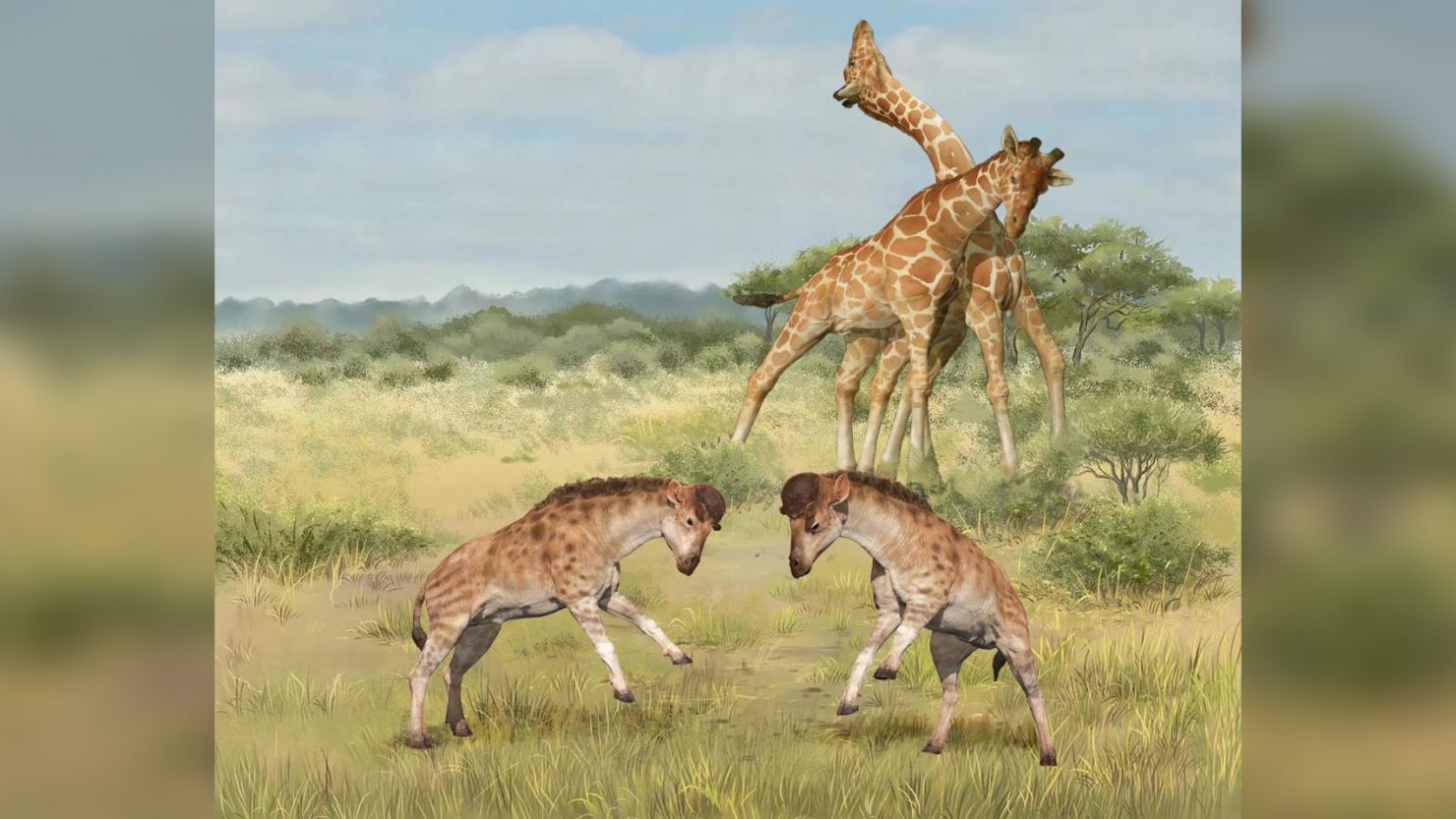

Since the time of Charles Darwin, scientists have tried to understand why the giraffe, the tallest land mammal, evolved such a long neck. Many researchers believed it was so the animal could reach tall foliage. As they studied giraffe behavior, they realized the long neck serves another purpose. When male giraffes compete for courtship with females, they use it to fight with one another.

The muscled necks, which can be 6.5 to 9.8 feet (about 2 to 3 meters) long, can be used to smash their heavy skulls, armed with skin-covered bony protrusions called ossicones, against the weakest parts of a rival’s neck. In short, the longer the neck, the greater the chance of inflicting serious damage.

As researchers studied Discokeryx xiezhi, they began to fill in the missing pieces of giraffe evolution, including the evolution of a long neck, fighting behaviors and environmental pressure to reach vegetation.

The male giraffe with the longest neck is at the top of the social hierarchy, and its need to compete for females is the driving force behind why its neck evolved to be so long.

A study detailing the findings published Thursday in the journal Science.

“Both living giraffes and Discokeryx xiezhi belong to the Giraffoidea, a superfamily. Although their skull and neck morphologies differ greatly, both are associated with male courtship struggles and both have evolved in an extreme direction,” said study author Shiqi Wang, an associate professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.

Built for headbanging

Discokeryx xiezhi had a heavily built cranium, or the thick bones that surround the brain. The roof of its skull was more than an inch (2.5 centimeters) thick, which was incredibly hefty for an animal about the size of a sheep, said study coauthor Jin Meng, curator-in-charge for fossil mammals at the American Museum of Natural History.

This skull roof also had a large, flat surface where it grew a single, large disklike horn for headbutting.

And the animal had a thick skull base and neck bones that were specialized to absorb extreme impacts, the researchers realized.

The complex articulations and joints between the skull and neck bones prevented the neck from breaking. That structure suggests Discokeryx xiezhi was better built for headbutting than just about any living animal, including musk oxen, who regularly experience head impacts.

The team compared horn structure in giraffes and giraffoids with cattle, deer, pronghorns and sheep, and determined that giraffes have a greater diversity of horn forms. This finding suggests that competition for mates is more intense than in other horned mammals.

Environmental pressure

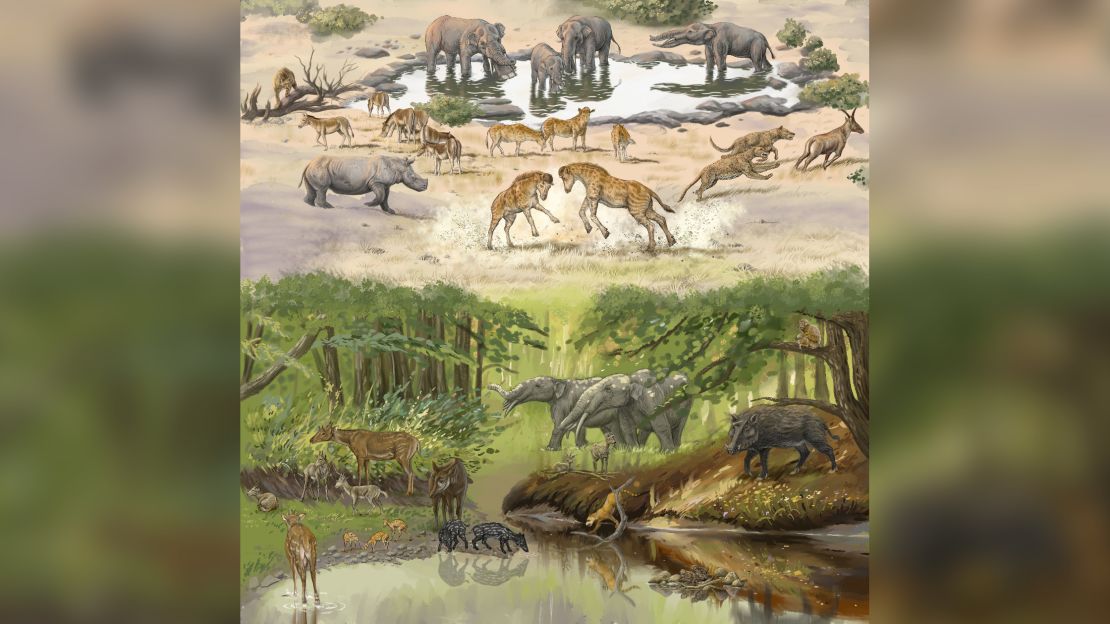

To determine Discokeryx xiezhi’s environment, the scientists studied its tooth enamel. They found that the giraffoid lived in open grasslands with patchy trees and shrubs and may have migrated based on the seasons. During the Miocene period 17 million years ago, Earth was warm and covered with forests.

The Xinjiang region, which was home to the giraffoid, was more arid due to the rise of the Tibetan Plateau in the south, which blocked the movement of water vapor. The drier climate created a more barren habitat, which may have created environmental pressures on Discokeryx xiezhi’s ability to survive – hence the intense fighting over females.

When early giraffes began to appear about 7 million years ago, they experienced a similar environment as the East African Plateau shifted from forest to open grasslands.

These giraffe ancestors had to adapt and may have developed their neck-fighting style, called “necking,” as a direct result to compete for courtship. As a result, the giraffe’s neck rapidly grew and evolved over a period of 2 million years, leading to the tall, long-necked mammal we know today.

A side benefit of the long neck also meant the giraffe could reach tall foliage that other animals couldn’t.

Previously, scientists thought there should be an ancestor of the giraffe with an intermediate-length neck. Instead, this evolution occurred more directly, rather than in stages, Wang said.

There are too few fossils, and only from a specific area, for researchers to know how long Discokeryx xiezhi lived or when it went extinct. Its predators likely included hyenas, saber-toothed cats and a giant bear dog called Amphicyon ulungurensis, Wang said.

Next, researchers hope to find a more complete fossil so they can learn more about this “strange beast” and compare it with other mammals, and even dinosaurs, to unlock the history of headbutting, Meng said.