Europe has finally proposed a ban on Russian oil, but has again stopped short of using its most potent weapon — sanctioning Russia’s natural gas.

On Wednesday, the European Commission put forward a sixth package of sanctions against Russia over the war in Ukraine, which includes a plan to phase out allcrude and oil products by the end of the year.

The oil embargo may yet be amended to give countries such as Hungary more time to adjust, but EU officials insist sanctions are coming.

Europe first targeted Russia’s vast energy reserves last month when it announced it would phase out Russian coal imports — worth about €8 billion ($8.4 billion) a year — by August.

Sanctions have so far spared Russia’s natural gas exports, which are predicted to generate about $80 billion in tax revenues for Moscow this year, according to Rystad Energy.

That would be a much bigger ask for Europe,which got 45% of its natural gas imports from Russia last year — a much bigger share than oil.But sanctioning gaswould deal asharp blow to the Russian economyand severely undermine President Vladimir Putin’s ability to finance his war. A full gas embargo byWestern allies wouldreduce Russia’s GDP by almost 3%, an analysis by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, published before the invasion, shows.

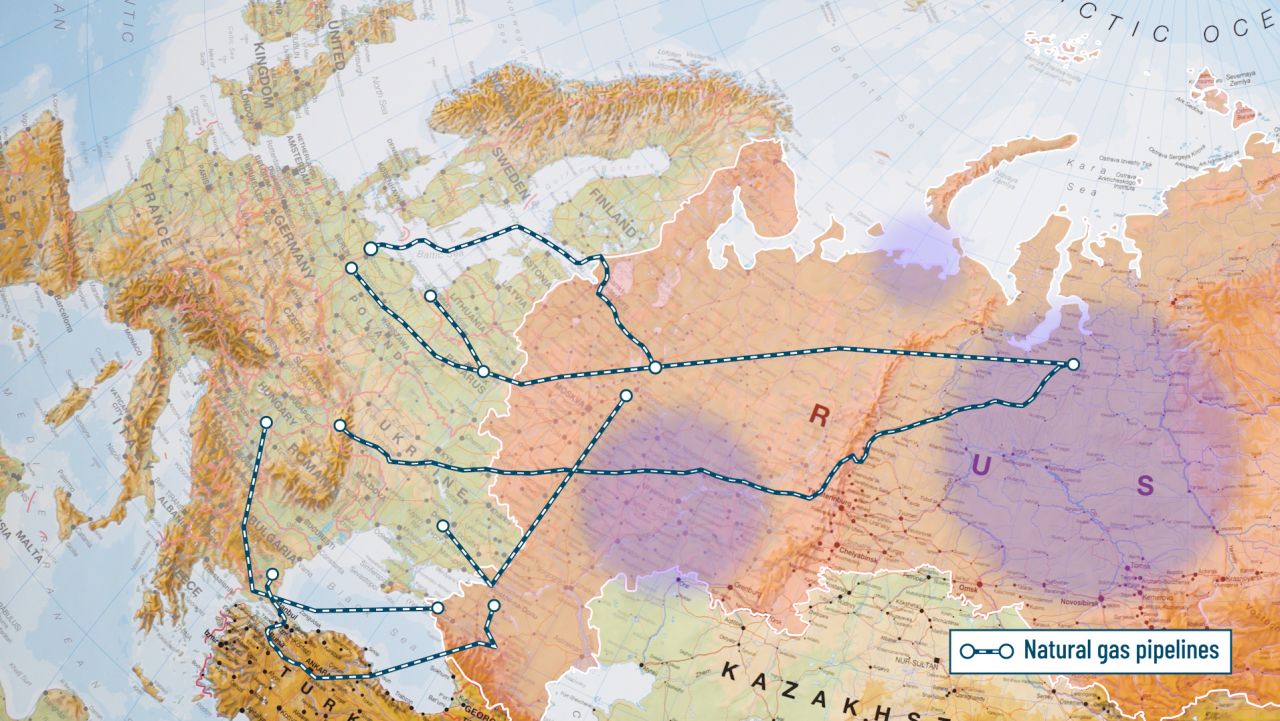

Europe is Russia’s biggest customer for gas, and the majority is delivered along pipelines. That would make it hard for Russia to divert supplies to other countries if the bloc was to turn off the taps.

Lithuanian Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė announced last month that her country would be the first to cut ties with Russia’s “toxic” gas.

A ‘new world of economic pain’

The rest of Europe is unlikely to follow, at least not for a while, but it is trying toreduce consumption by 66% by the end of this year, and to break its dependence completely by 2027.

Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank, told CNN Business thatthose goals were “tough but possible,” but he doesn’t thinkEurope will go much further and adopt formal sanctions on gas.

“If we get the full embargo, then, of course, we’d be talking about a likely recession in the eurozone,” he said.

Dependency on Russian gas varies wildly across the bloc. A sudden break would spell disaster for some EU countries, including major economies such as Germany and Italy.Germany relied on Russia for nearly 46% of its gas consumption in 2020, and Italy 41%.

As a result, analysts at S&P Global Commodity Insights do not expect EU sanctions on Russian natural gas to come before 2024.

“[They] would likely be a phase down rather than an abrupt cut,” Kaushal Ramesh, senior analyst at Rystad Energy, told CNN Business.

“And [they] would likely incorporate flexibilities for exemptions for some of the more dependent countries.”

There is, of course, another way Europe may have to confront a sudden loss of Russian gas. Moscow could turn off the taps.

State energy giant Gazprom said last week it had cut gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria, making good on President Vladimir Putin’s threat to halt deliveries to “unfriendly” countries must open two accounts at Gazprombank — one in euros and the second in rubles, from which payments for the gas would be made.

Further cut offs appear unlikely for now, although not impossible, and a tense stand-off continues. EU officials and European governments insist that contracts must be honored, but some energy companies are exploring whether the new payment arrangement might be consistent with Western sanctions.

Still, Russia’s willingness to turn off the taps has rattled countries dependent on its exports. Ramesh thinks the European Union is between a rock and a hard place.

Sanctions on gas would mean a “whole new world of economic pain,” he said, but that should “be balanced against the idea of Russia unilaterally stopping flows.”

“[This] is a scenario of lasting uncertainty,” he added.

While neighboring countries have stepped in to share their gas supplies with Poland and Bulgaria, a similar response could be harder to orchestrate under an EU-wide embargo.

The bloc’s gas storage facilities are about 34% full, according to data from Gas Infrastructure Europe. That’s about normal for the time of year, but will onlybe enough to get it through to the end of 2022 without additional imports.

“We would then have trouble next winter,” Schmieding said.

Europe is quickly diversifying its energy sources in a bid to avert disaster. Imports of liquified natural gas (LNG) hit a five-year high in April, and gas flows from Norway are up 17% from last week, Rystad Energy said.

Could Germany cope?

Germany has so far been reluctant to go after Russia’s gas. It is the world’s biggest buyer, according to data from the US Energy Information Administration.

Europe’s biggest economy has reduced Russia’s share of its gas imports to 40% from 55% before the war in Ukraine, but says it needs to keep buying from Moscow over the next few months to avoid a deep recession.

“We know there is a dependency on natural gas from Russia, it is a reality. We need time to reduce this dependency,” Christian Lindner, Germany’s finance minister, told CNN’s Julia Chatterley on Monday.

German gas distributor Uniper said last week that it cannot cope without Russian gas in the short term.

“This would have dramatic consequences for our economy,” the company said in a statement.

A full gas embargo would cause severe harm to Germany’s energy-intensive manufacturing industry. About 550,000 jobs and 6.5% of annual economic output could be lost across this year and next, according to an analysis by five of the country’s top economic institutes.

Even a more gradual phase out would inflict pain. Fears of a supply crunch have caused wholesale gas prices to rocketsince Russia invaded Ukraine, helping push producer price inflation — that’s the price of goods leaving factories — above 30% in March, the highest level in 73 years.

Prices at the factory gate are also feeding into consumer price inflation, which hit a 41-year high that same month.

The country has ramped up LNG imports and is accelerating the construction of LNG terminals, the economy ministry said in March. This, along with other efforts to diversify and save energy, would allow Germany to cut Russia’s share of its gas consumption to just 10% by 2024, it said.

Draining Russia’s war chest?

EU sanctions on Russia’s gas would strike at the heart of the country’s economy. It is the world’s largest natural gas exporter, with the 74% going to European customers, according to the EIA.

Despite countries rapidly winding down their imports, soaringenergy pricesover the past 12 months have been a boon for Russia.

The EU imported €44 billion euros ($47 billion) worth of Russian fossil fuels in the first two months of the war in Ukraine, a report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air shows. That’s more than double the value imported by the EU over the same period last year, CREA lead analyst Lauri Myllyvirta told CNN.

European natural gas futures were trading above€106 ($112)per megawatt hour Thursday, up 25 from the day before the invasion, according to Refinitiv data.

Russia has also managed to ramp up deliveries of its crude oil to Indiain recent weeks as a de facto embargo among banks, traders and shippers has taken hold. India has bought about 25 million barrels of Russia’s Urals crude between the start of the invasion and late April, compared to about 11 million barrels for the whole of last year, data from commodity analysis firm Kpler shows.

But diverting its natural gas deliveries would be a far more difficult task. Most of Russia’s gas flows over pipelines, which take years to build.

Kateryna Filippenko, principal analyst for global gas supply at Wood Mackenzie, told CNN Business that there is “simply no infrastructure” for Russia to divert gas to Asia.

“Potentially they could send some more LNG towards Asia, but the capacity of LNG is fairly limited,” she added.

Russia is planning to build new pipelines from Siberia to Asia, Schmieding said, but this would take a long time.

“Probably by the time it happens global demand, in reaction to high prices now, would be significantly lower than it would have been otherwise,” he said.

— Mark Thompson and Jack Guy contributed reporting.