Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Pterosaurs ruled the skies during the age of the dinosaurs, but scientists have long debated if they actually had feathers.

Now we know. Not only did these flying reptiles have feathers, but they could actually control the color of those feathers on a cellular level to create multicolor plumage in a way similar to modern birds, new research has revealed.

These color patterns, determined by melanin pigments, may have been used as a way for pterosaur species to communicate with each other. A study detailing these findings published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

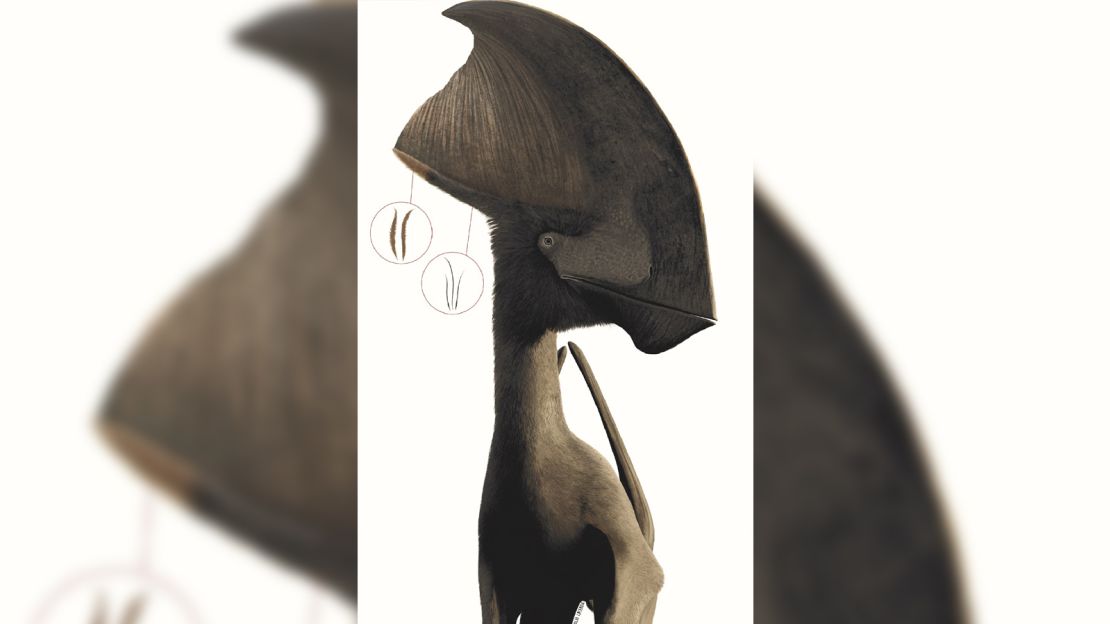

Researchers analyzed the fossilized headcrest of Tupandactylus imperator, a pterosaur that lived 115 million years ago in Brazil. Upon closer inspection, the paleontologists realized that the bottom of this huge headcrest was rimmed with two kinds of feathers: short, wiry ones that were more similar to hair, as well as fluffier ones that branch like bird feathers.

“We didn’t expect to see this at all,” said lead study author Aude Cincotta, a paleontologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University College Cork in Ireland, in a statement.

“For decades, palaeontologists have argued about whether pterosaurs had feathers,” Cincotta said. “The feathers in our specimen close off that debate for good as they are very clearly branched all the way along their length, just like birds today.”

The research team studied the feathers with electron microscopes and were surprised to find preserved melanosomes, or granules of melanin. These granules had different shapes, depending on the types of feathers they were associated with on the pterosaur fossil. Patchy color was also found in the preserved soft tissue.

“In birds today, feather colour is strongly linked to melanosome shape,” said study coauthor Maria McNamara, professor of paleontology in the University College Cork’s School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, in a statement.

“Since the pterosaur feather types had different melanosome shapes, these animals must have had the genetic machinery to control the colours of their feathers. This feature is essential for colour patterning and shows that coloration was a critical feature of even the very earliest feathers.”

Previously, scientists understood that pterosaurs had some kind of whisker-like fluffy covering to help keep them insulated. The new research confirms that this fuzz was actually made from different types of feathers. These feathers and the surrounding skin had different colors, like black, brown, ginger, gray and other tones associated with the different melanin granules.

“This strongly suggests that the pterosaur feathers had different colours,” McNamara said. “The presence of this feature in both dinosaurs (including birds) and pterosaurs indicates shared ancestry, where this feature derives from a common ancestor that lived in the Early Triassic (250 million years ago). Colouration was therefore probably an important driving force in the evolution of feathers even in the earliest days of their evolutionary history.”

Some of these colors helped the pterosaurs to share visual signals with one another, but the team isn’t quite sure what those signals would have meant.

“We would need to know the precise hue and pattern to work this out,” McNamara said. “Unfortunately we can’t do either at the moment, with current data. We need to look at melanosomes in feathers across the body to work out whether they were patterned, and we need to figure out whether traces of non-melanin pigments can be detected.”

Tupandactylus was an odd-looking creature, with a wingspan of 16 feet (5 meters) and a huge (albeit lightweight) head with toothless jaws. Its giant crest had irregular blooms of color.

“Perhaps they were used in pre-mating rituals, just as certain birds use colourful tail fans, wings and head crests to attract mates,” wrote Michael Benton, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, in a News and Views article that published with the study. Benton was not involved in the research.

“Modern birds are renowned for the diversity and complexity of their colourful displays, and for the role of these aspects of sexual selection in bird evolution, and the same might be true for a wide array of extinct animals, including dinosaurs and pterosaurs,” Benton wrote.

The discovery could allow for a better understanding of pterosaurs, which first appeared about 230 million years ago and went extinct along with the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

“This finding opens up opportunities to explore new aspects of pterosaur behaviour, and to revisit previously described specimens for further insights into feather structure and functional evolution,” McNamara said.

The fossil, originally recovered from northeastern Brazil, has been repatriated to its home country thanks to efforts by the scientists and a private donor.

“It is so important that scientifically important fossils such as this are returned to their countries of origin and safely conserved for posterity” said study coauthor Pascal Godefroit, paleontologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, in a statement. “These fossils can then be made available to scientists for further study and can inspire future generations of scientists through public exhibitions that celebrate our natural heritage”.