This year marked the 10th edition of the East African Safari Classic, one of the world's toughest rallies. Held over nine days in February, drivers like US professional Ken Block (pictured driving a Porsche 911) compete alongside local drivers, and this year, the first all-indigenous Kenyan team.

The route for the 2022 race covered thousands of kilometers over the course of nine days. Italian driver Federico Polese races in a Porsche 911 with a helicopter tracking the action.

Husband and wife team Lynda and Tony Hughes from Britain race in their Ford Capri.

"It doesn't matter what your upbringing was, what your tribe was, your educational status or even your age. (Rally racing is) one thing that actually brought everyone together," photographer Mwangi "Mwarv" Kirubi says of Kenya's longstanding relationship with the sport.

The rally is raced "blind," meaning teams are only given the stage routes less than a day before -- so there's no time to inspect the terrain in advance.

Kenyan Eric Bengi and his co-driver Peter Mutuma traverse a stream during the African Rally Championship (ARC) Equator Rally Kenya at Soysambu Conservancy in Nakuru, on April 24, 2021. In 2022 Bengi would become one half of the first all-indigenous Kenyan team to participate in the East African Safari Classic alongside compatriot Mindo Gatimu -- an important moment in the long history of the rally.

The race was first established as the Coronation Rally in 1953, to honor the soon-to-be crowned Queen Elizabeth II, when Kenya was still part of the British Empire. The rally took place between Kenya, Uganda and part of present-day Tanzania, and was timed to finish during her coronation ceremony. Pictured: W.F.C. Young and L. Baillon in their Ford in the 1959 Coronation Rally.

The Coronation Rally changed its name to the East African Safari Rally in 1960. Pictured: 1963 East African Safari winners Nick Nowicki and Paddy Cliffe shake hands over the bonnet of their Peugeot car.

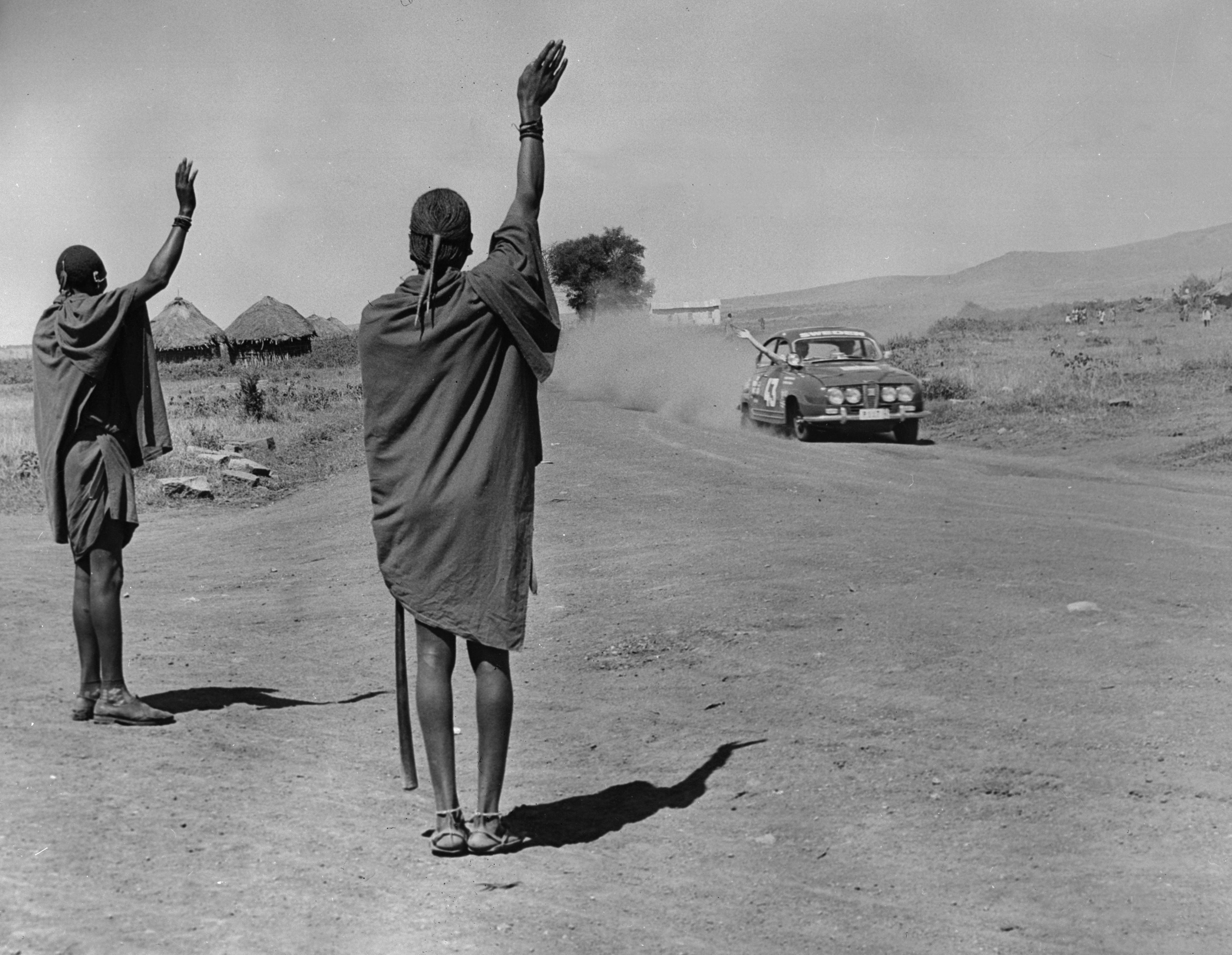

Competitors Pat Moss-Carlsson and Elizabeth Nystrom exchange a wave with Maasai onlookers during practice for the 1966 East African Safari Rally.

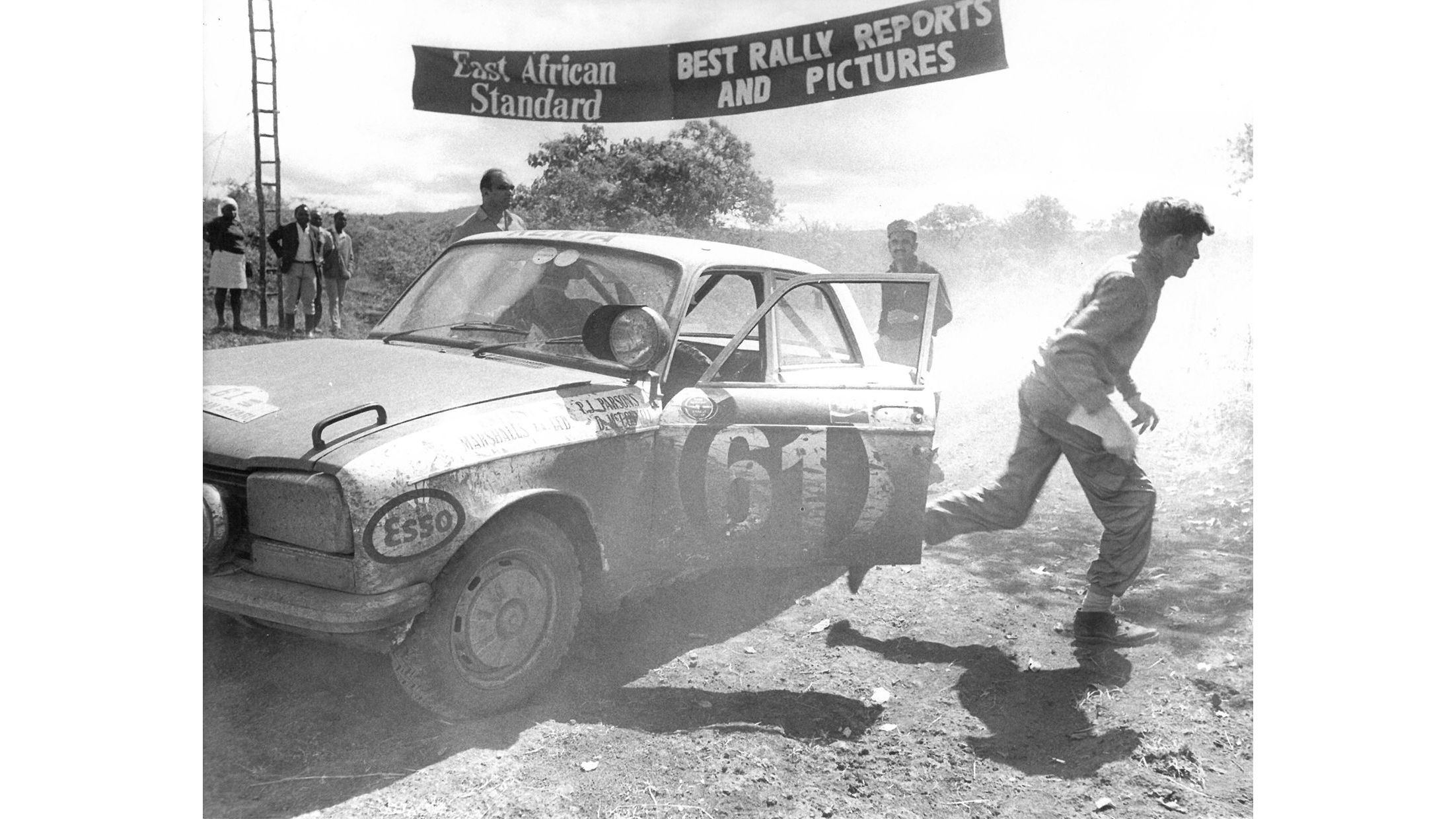

Robin Hillyer and John Arid drive the 3,075-mile (4,950-kilometer) 1968 East African Safari Rally in their Lotus Cortina.

A team receives a push through deep mud in Usumbaras, Tanzania during the 1968 race. As is the case with the classic rally now, the public were permitted to help drivers who got stuck.

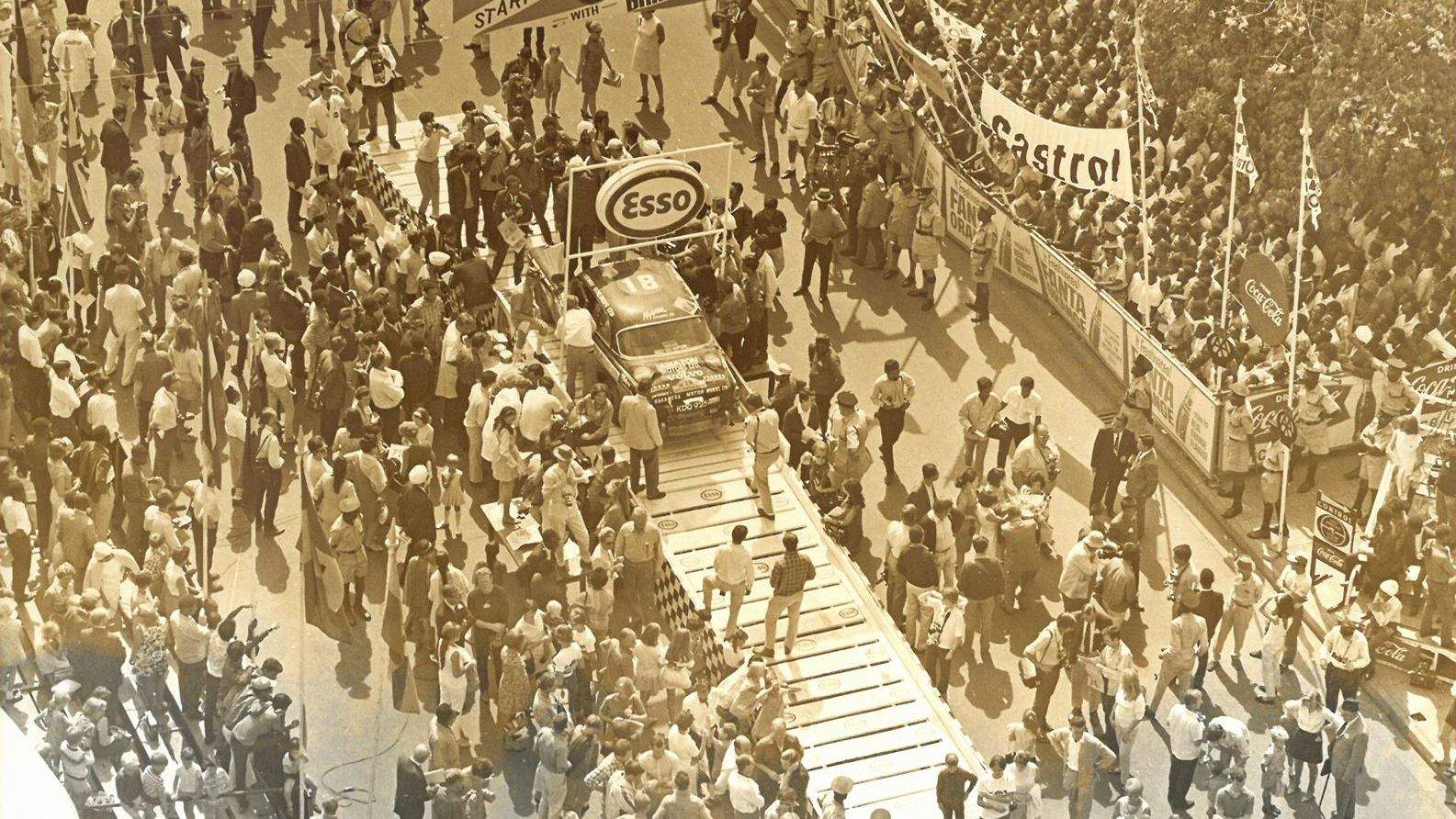

Hundreds of spectators gather outside City Hall, Nairobi to watch the flagging off of the 1969 East African Safari Rally.

A car makes a stop during the 1971 East African Safari Rally. The rally was raced across multiple countries in its earlier iterations, and became part of the World Rally Championship (WRC) calendar in the 1970s.

A car drives through a rural area during the 1971 rally. The nature of the event is heavily determined by local conditions, which range from incredibly dusty to heavy mud, putting vehicles and their drives through their paces.

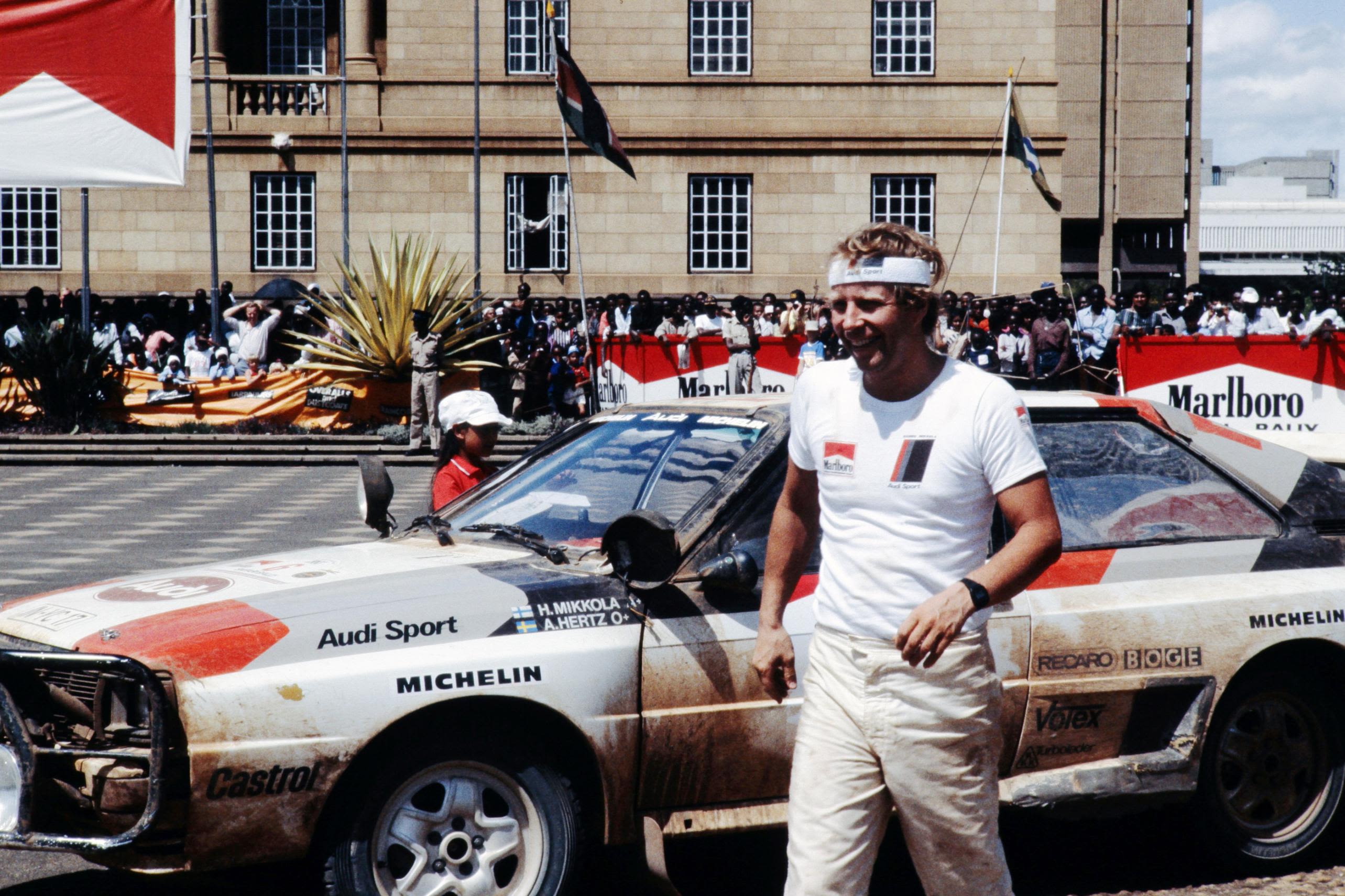

Hannu Mikkola at the 1983 Marlboro Safari Rally in Nairobi. The late Finnish driver took second place in the WRC event.

A Maasai warrior watches Petter Solberg and Phil Mills compete in the first leg of the 2000 Sameer Safari Rally, south of Nairobi. The Norwegian and Briton would finish fifth in the three-day World Rally Championship event.

A spectator perched on a railway crossing sign watches Finnish driver Tommi Makinen in action in his Mitsubishi Lancer Evo VII during the 2001 Safari World Rally Championship.

Britons Stuart Rolt and Richard Tuthill receive assistance from the public near Mombasa, southeast Kenya, during the 2003 East African Safari Classic. Fifty three cars lined up to race that year, each manufactured in 1971 or earlier.

Japanese driver Takamoto Katsuta and British co-driver Daniel Barritt race through Kasarani near Nairobi in their Toyota Yaris ahead of the Safari Rally Kenya last year. With the event, the World Rally Championship returned to the country after a 19-year absence.