When protests swept Kazakhstan earlier this month, they were fueled by frustration with the ruling elite and entrenched inequality. But the unrest was sparked by a specific catalyst: an end to a government subsidy.

The cost of liquefied petroleum gas — whichmost people in the western part of the country use to power their cars — doubled overnight after the government lifted price caps. The ensuing turmoil, which saw thousands of protesters take to the streets, resulted in a Russian-led military intervention, the resignation of the government and the deaths of more than 200 people.

The episode is a reminder of the challenges facing governments that want to tackle longstanding fuel subsidies, either to reform markets and save money, as was the case in Kazakhstan, or to encourage people to switch to cleaner energy.There’s a consensus that eliminating these subsidies soon is crucial to reaching net-zero emissions targets and averting the worst effects of the climate crisis.

“The overall direction of travel has got to be a quick move away from subsidies,” said Peter Wooders, senior director of energy at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. “This isn’t something we want to be talking about in 10 years, and ideally not something we want to be talking about in five years.”

But rolling them back is a tricky task that requires careful maneuvering. Spiking energy costs are a frequent spark for political conflict, especially when trust in government leaders is already low.

The challenge is made harder by the fact that energy prices are rising sharply around the world, piling pressure on the most disadvantaged. Eliminating subsidies for consumers at such a moment would exacerbate that pain and amplify discontent.

The situation in Europe looks particularly perilous in the coming months. Natural gas prices have soared, and tension with Russia over Ukraine could send them even higher. In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government faces mounting criticism over plans to raise a cap on household energy bills in April.

Government technocrats “know they need to get rid of” subsidies, said Glada Lahn, an energy policy expert at the think tank Chatham House in London. “But politically, it’s difficult.”

An end to subsidies

The value of government subsidies for fossil fuels dropped to $375 billion in 2020, their lowest in the past decade, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the International Monetary Fund and the International Energy Agency.

Yet that decline was mostly tied to the plunge in energy prices, which meant governments didn’t have to pay as much to suppress costs for consumers. In 2021, subsidies shot back up again, IISD’s Wooders said.

There are two main categories of subsidies for fossil fuels — those for consumers, which bring energy costs below market rates to lower the burden on the public, and those for producers, which can be harder to track, since they include tax breaks, loan guarantees and access to cheap credit. About three-quarters of global fossil fuel subsidies are for consumers.

In countries rich inoil and gas, consumer subsidies are often part of the social contract. Wealth from the energy sector is channeled to the government or business elites, so subsidies are seen as an important mechanism for redistributing those benefits more broadly.

Still, research shows that these policies tend to disproportionately benefit higher income segments of the population, since wealthy people are more likely to own cars that need gas and to use more electricity.

They’re also a major impediment to slashing emissions, which needs to happen immediately to fight the climate crisis.

Subsidies encourage over-consumption by businesses and households, and reduce the urgency of limiting waste. They also eat up huge parts of government budgets that could be used for sustainable projects like greener public transport.

An IISD study published last year found that removing fossil fuel subsidies for consumers across 32 countries would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 6.1% by 2030. In some countries, emissions would drop by more than 30%.

“Phasing out the subsidies would provide more efficient price signals for consumers, and spur more energy conservation and measures to improve energy efficiency,” the IEA said in its roadmap for achieving net-zero emissions.

The group’s researchers said consumer subsidies must be eliminated to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Doing it right

Progress is possible. At least 12 countries took steps to reduce fossil fuel subsidies between the middle of 2020 and themiddle of 2021, according to IISD.

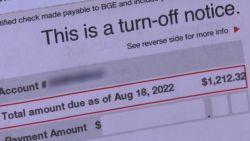

But the removal of subsidies can be a lightning rod for dissent since it hits residents’ pocketbooks immediately. Problems can also arise when people don’t believe their government will fairly invest or redistribute the money they’d otherwise spend on reducing energy costs.

“Fuel subsidy cuts definitely can be a leading indicator for protests,” said Hugo Brennan, an analyst at risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft.

In Kazakhstan, protests started in the western city of Zhanaozen over a leap in the price of butane and propane, which is often used as a cheaper alternative to gasoline. Yet demonstrations soon tapped into deeper sentiments.

“What’s really going on [is] people are angry about inequality, about inflation and a lack of political freedom,” said Melinda Haring, deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. Kazakhstan’s government opted to restore the price caps for six months.

It’s just one example. After Ecuador’s government announced the removal of fuel subsidies in late 2019, the country experienced a wave of protests that occasionally turned violent. The government ultimately reversed course. India, Indonesia, Yemen and Jordan have also been rocked by unrest tied to the rollback of fuel subsidies over the past 15 years.

Nigeria’s government is trying toremove gasoline subsidies for consumers this year. While the subsidies mean prices at the pump are among the lowest in the world, the World Bank has reported that they mostly help the wealthiest members of the population and entice smugglers. Still, large-scale protests one decade ago and the failure of previous attempts underscore how fraught the process will be.

Concerns about fuel prices also affect the richest countries. In France, the gilet jaunes or “yellow vest” protest movement kicked off after President Emmanuel Macron’s government announced a new eco-tax on fuel in 2018, generating backlash among the country’s working and middle class living outside of major cities.

“These people needed to have purchasing power to get gas in their car so that’s why the protest began,” Samy Shalaby, an early yellow vest activist, told CNN in 2019. “But after that the people wanted to do more than challenge one tax, they wanted to change the democracy … the entire economic model.”

To successfully roll back subsidies, governments need to plan well in advance, Wooders said. The impact on lower-income households can be mitigated by providing direct cash payments to offset price increases — an approach that tends to be much cheaper than maintaining fuel subsidies in the long run. Communication about the move also needs to be deliberate and clear, and leaders should consider a phased approach, he added.

But with energy costs already skyrocketing, anger over inflation smoldering and pandemic fatigue setting in, leaders that want to address subsidies will need to tread carefully.

“The Kazakhstan unrest already demonstrates that people are increasingly price-sensitive to oil products, with more ‘Pandemic Spring’ protests related to energy or government handling of Covid-19 being a risk,” Louise Dickson, an oil market analyst at Rystad Energy, said in a note to clients on Monday.