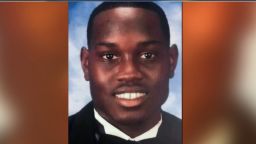

The shooting death of a Georgia man has thrust a complicated and often misunderstood legal tenet into the spotlight. The concept of “citizen’s arrest” is a common cultural trope, but it’s also at the center of the case of Ahmaud Arbery, a black man who was shot and killed after a pair of men pursued him with the alleged intent of making such an arrest.

While the practice of citizen’s arrest holds an important place in American history and community enforcement, the specifics are often hard to nail down, and even harder for law officers and attorneys to enforce and litigate. Here’s what you need to know about what it really means to conduct a citizen’s arrest – and just as importantly, what it doesn’t mean.

What the law says about citizen’s arrests

Laws governing citizen’s arrests vary from state to state, and that’s the first problem in understanding what they entail. However, there are some commonalities: In general, citizen’s arrest laws let a citizen detain someone if they have committed a crime. What kind of crime, and what kind of evidence someone needs to make a citizen’s arrest, can vary.

What purpose they serve

“States let people arrest other people who are committing crimes, which promotes good law enforcement,” says Michael Moore, a former US Attorney who now practices in Georgia. “It also eliminates the possibility that someone will be held liable if something happens after the fact.”

For instance, Moore says, if a citizen stops a purse snatcher in the act and the snatcher falls down and breaks their arm, under citizen’s arrest laws, the citizen who stopped them can’t be held liable.

Why laws can be hard to interpret

In Georgia, where Arbery was killed in February 2020, the state code at the time described the grounds for arrest by a private person like this:

“A private person may arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge. If the offense is a felony and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape, a private person may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.”

Different laws – whether in state codes, precedents set by state court rulings or some other common legal understanding – sometimes mention use of force, as in New York state, where non-deadly use of force is specifically allowed. Other citizen’s arrest laws specify whether the law can be used for felony or misdemeanor crimes. Some also specify whether someone had to witness the crime actually being committed in order to pursue an arrest.

“There’s a lot of nuance, and these cases are very facts-specific,” Moore says. For instance, does “immediate knowledge” mean someone has to see a crime being committed? Moore says if he were trying a case in Georgia, he would want to know details of what led to the arrest. “You would need to know: How are (the arresters) claiming that they had immediate knowledge of a felony being committed? Did they see something, hear something?”

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp announced an overhaul of the state’s citizen’s arrest law in February 2021, a year after Arbery’s killing.

Under the new law, a detained offender must be released or the person conducting the citizen’s arrest must call law enforcement within an hour. If authorities do not arrive within an hour, the detainee must be released, according to CNN affiliate WGCL-TV.

A provision is included prohibiting the use of force that is likely to cause death or great bodily harm to detain someone … unless the detention is to protect self, others, ones’ habitation, or to prevent a forcible felony, WGCL reported.

What happens during a citizen’s arrest

Once a citizen makes an arrest and contacts qualified law enforcement, those law enforcement officers immediately assume authority.

Thomas Aveni, the executive director of the Police Policy Studies Council, outlines what comes next:

“What’s taught to police recruits is, ‘Detain both, ascertain the facts, proceed,’” he says. “In my experience, you would see both the citizen making the arrest and the person arrested both detained and the citizen would be compelled to give a statement with regard to what he or she saw.”

What risks a citizen’s arrest carries

While Aveni says a law enforcement officer doesn’t always act as an arbiter of whether or not the arrest was justified, if it is found to be baseless or arbitrary, there are consequences for the arrester. “Generally there are sanctions regarding false arrests or false detention, and then the citizen is putting themselves in jeopardy in terms of liability,” he says.

Aveni says that while the concept of a citizen acting as temporary law enforcement dates back hundreds of years, it is not necessarily encouraged today.

“Police departments generally do not encourage citizens to make arrests or detentions,” he says.

“Many agencies do set up community watch committees. But when you start putting together a community watch, most agencies will make it clear you, the citizen, are just eyes and ears. This is where effective community relations comes in. Police interface with their communities on a regular basis, and certainly it’s a topic worth discussing.”

What people get wrong about the laws

While the ways citizen’s arrest laws are written are often subject to interpretation, generally speaking, there are things they do not allow.

“I think some people see the laws as license to become a cowboy, or that somehow it deputizes you to become a cop. It doesn’t. We still have police.” says Moore. “What you can’t do is use that to go out and become a detective and patrol the streets. You can’t base your actions on hearsay.”

Moore says a lot of these misinterpretations are similar to ones people have for self-defense laws. “These laws are there for a good reason and that is to protect your life. But you can’t create the crisis,” he says.

What the Ahmaud Arbery case tells us about the law

Every case has its specific factors. In the case of Arbery’s death, there is video of his killing. One of the men arrested and charged with Arbery’s murder is also a retired police officer. Then, there are Georgia’s specific citizen’s arrest laws, which Aveni says are particularly loose.

“This is why we have juries,” he says. “Because this may come down to whether this was a reasonable intervention.” According to a district attorney who has since recused himself from the case, Gregory McMichael, the 64-year-old ex-police officer who, along with this son Travis are charged with Arbery’s murder, was involved in a previous investigation of Arbery. Aveni says this could be another complication.

“The concerns are, what did (McMichael) know? What did he reasonably believe? Did prior knowledge of this person’s history affect his outlook? Did his son (Travis McMichael) reasonably believe a crime had been committed?”

These are the questions one has to pay special attention to when legal concepts like citizen’s arrest laws rely on inexact factors like perception, motivation, intent and interpretation. The facts become even more important in finding clarity among the confusion.