Schools are in session, Covid-19 restrictions are being relaxed en masse and the Delta variant is raging worldwide, creating a maelstrom of confusion for parents on how to best protect their unvaccinated children.

Data from earlier in the pandemic showed that children are less likely to become seriously ill. The emergence of Delta has been a game changer, however, destroying the myth that healthy kids can’t get hit hard by the virus.

While many high-income nations, including the United States and most members of the European Union, now offer Covid vaccines for children 12 and older, a handful of countries have now authorized the shot for younger people. Meanwhile, severe vaccine inequality persists on a global level, with many developing nations continuing to struggle to provide first and second doses to high-risk groups – with the very idea of getting shots to children still a pipe dream.

Here’s a global snapshot of where things stand.

Where children under 12 are being vaccinated

Cuba became the first country in the world to vaccinate children as young as 2 this month, with the government saying that its homegrown vaccines are safe for younger kids. The island nation initially planned to focus on vaccinating healthcare workers, the elderly and the hardest-hit areas. Then, following a spike in infections among children attributable to Delta, it announced that it would also prioritize young children in a bid to safely reopen classrooms.

Throughout the pandemic, most in-person classes have been suspended in Cuba. Students have been primarily learning through educational television programming instead, as home internet remains a rarity on the island.

Cuba has yet to provide data on its vaccines to outside observers, but has said it will seek World Health Organization (WHO) approval on Thursday.

Chile, China, El Salvador and the United Arab Emirates have also approved vaccines for younger children. In Chile, children aged 6 and older can get the Sinovac shot, while in China, the Sinovac and CoronaVac vaccines are authorized for use in children as young as 3. In El Salvador, children as young as 6 will soon be able to get vaccinated, while in the United Arab Emirates – where Sinopharm is approved for 3-year-olds – the government has made it clear that the vaccination program will be optional.

Meanwhile, American children between 5 and 11 could be eligible for the vaccine sometime this fall, pending approval from the US Food and Drug Administration. Pfizer’s CEO said Tuesday that the company plans to submit data on its vaccine from studies involving that age group by the end of this month.

Where governments are still weighing up what to do regarding younger children

The United Kingdom has been more cautious than many other European countries in regard to vaccinating younger populations, only recommending the shot for 12-15 year olds on Monday, following advice from its chief medical officers. The move ended months of debate among scientists and government, and places it in line with the US and many other European countries that have been vaccinating this age group for months.

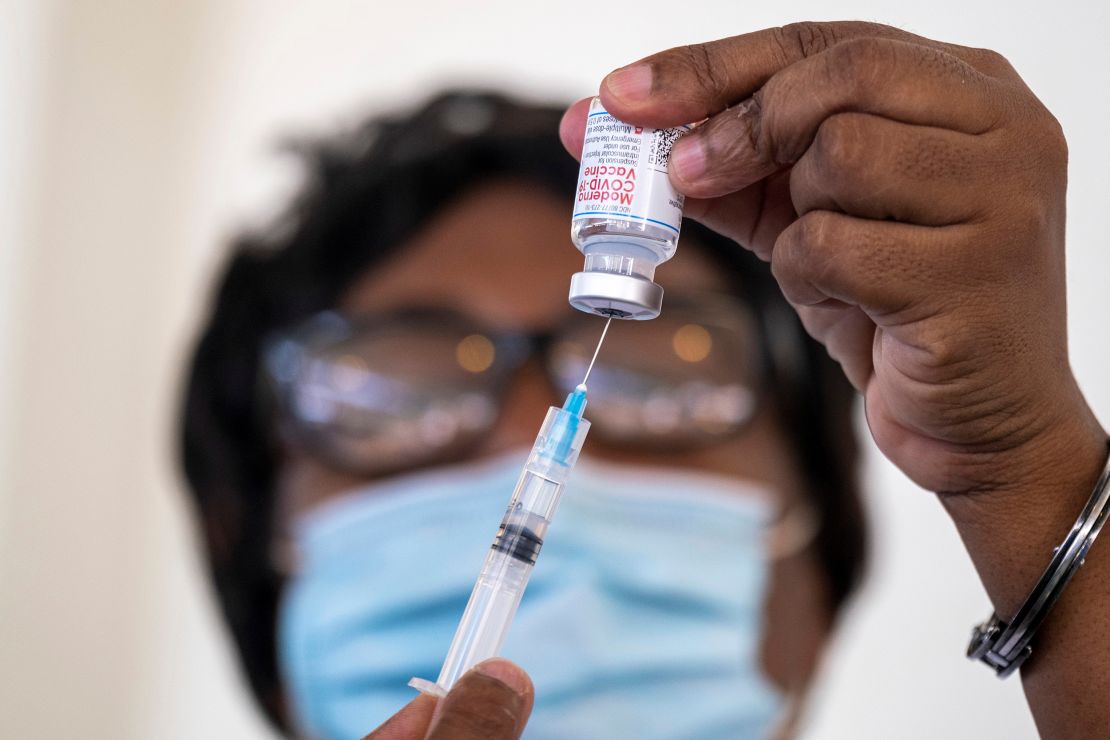

In late May, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the use of Pfizer/BioNtech’s vaccine for children aged 12-15, based on a trial that showed that the immune response to the vaccine in that age group was comparable to the immune response seen in people from 16-25. The EMA approved the Moderna vaccine for 12-15 year olds in late July.

France, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Poland are among EU countries that have rolled out their vaccination campaigns for 12-15 year olds, with uptake varying across the bloc.

Switzerland – which is not part of the EU – has been vaccinating the younger age group since June. Sweden will offer the vaccine to 12-15 year-olds later in the fall, Sweden’s Prime Minister Stefan Lofven said Thursday.

Meanwhile, in the UK there are no current plans to vaccinate children under 12, according to Chris Whitty, England’s chief medical officer.

The UK’s current guidelines for 12-15-year-olds were put forward in the hope that they will reduce the spread of the virus in schools, Whitty said. He noted, however, that vaccinations aren’t a silver bullet and that policies to minimize transmission should remain in place. Teenagers will get just one dose of the vaccine for now.

The new guidance has also reinvigorated a debate on consent in the UK, especially when a parent and child disagree. While parents in Britain generally need to authorize vaccination for children under 16, children can overrule vaccine-hesitant parents if a clinician considers them “competent” to do so.

Where vaccinating under-12s is not an option because there aren’t enough doses

While more than 42% of the global population has had at least one dose of the vaccine, only 1.9% of people in low-income countries have received at least one shot, continuing to leave billions at high risk of disease and death when exposed to Covid-19.

Haiti only received its first vaccines in July, with the delivery of 500,000 doses donated by the US through the COVAX vaccine-sharing program. Fewer than 1% of the country’s 11.4 million people – of whom nearly a third are under the age of 14 – have been vaccinated so far.

In May, when some high-income countries began vaccinating children and other low-risk groups, World Health Organization chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said they were “doing so at the expense of health workers and high-risk groups in other countries.”

Where vaccinations for children could be more difficult to roll out

While no countries appear to have categorically ruled out inoculating younger children so far, vaccine hesitancy among policy makers could play a part in countries apparently uncertain about doing so.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, just over 120,000 doses have been administered – leaving under 0.1% of the country’s population of 90 million protected. Last week, the country received 250,000 doses of the Moderna vaccine, donated by the US through COVAX. Another 250,000 Pfizer doses are to follow shortly.

However, vaccine skepticism remains high in the country, with prominent leaders, including the president, contributing to that hesitancy.

In March more than 1.7 million AstraZeneca doses arrived in Kinshasa, but the government delayed its rollout after reports of rare blood clots and then exported about 75% of the shipment.

On Monday, after waiting for six months, DRC President Félix Tshisekedi got vaccinated, saying after his first dose of the Moderna shot that “by this act I want to show my compatriots that it is really necessary to take the vaccine and that it is not necessary to worry.” He added that his wife had also taken the vaccine, and then urged others to do so, “because it saves lives.”

The change in messaging might leave public health officials hopeful for getting more shots in arms in the months ahead. But how that will play out in terms of vaccinating children remains unclear in a country where misinformation on vaccines runs rife and where, earlier this year, around 70% of healthcare workers said they would not get the shot.

CNN’s Patrick Oppmann, Larry Madowo, Jack Guy and Niamh Kennedy contributed to this report.