When it comes to making history, Beijing’s universities have played an outsized role: they were the source of the demonstrations which kicked off the May Fourth Movement, to which the Chinese Communist Party traces its roots, and the Tiananmen Square protests, perhaps the biggest challenge to the CCP since it took power.

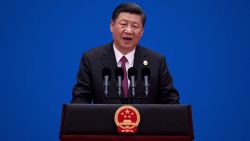

So it makes sense then that President Xi Jinping, as he looks to further consolidate his rule ahead of the Party’s centennial later this year, would pay special attention to the country’s top schools.

In a visit to Tsinghua University this week, Xi praised the Beijing institution for cultivating a “glorious tradition of patriotism” and encouraged students to be “both red and professional,” a phrase which dates to the Mao Zedong era.

“Be firm in your beliefs, always stand with the Party and the people, and be a firm believer and faithful practitioner of socialism with Chinese characteristics,” said Xi, adding that “a splendid flower blooms in the unremitting struggle.”

Along with several other elite Beijing institutions, Tsinghua is one of China’s top universities, and graduates can be expected to take up key roles in the future in government and business. If the Party is to maintain its ideological stranglehold on the country, it will depend on this next generation of thinkers to follow the leadership of Xi’s cohort.

The Chinese leader was himself a Tsinghua student in the 1970s, but his education was disrupted by the Cultural Revolution, a decade of bloody political and social upheaval initiated by Mao’s attempts to shore up control of the Party and country. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed as parts of the country fell into something approaching civil war, while millions more were displaced and traumatized as society broke down around them.

Only ending with Mao’s death, the Cultural Revolution broke many people’s faith in Communism, and was followed by capitalist reforms and opening up, a major proponent of which was Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, who along with future paramount leader Deng Xiaoping was purged several times during the Mao years.

Today, however, as Xi’s government prepares for the grand centennial celebrations, the events of 1966-76 are, like any other blemishes in the Communist Party’s record, best forgotten. Under Xi, the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao himself, the Party is once again ascendant, taking an active role in all levels of society.

This month, Beijing launched a campaign to promote the correct study of “Party history” and to root out “historical nihilism,” that is, discussion of history in a way that does not conform to the official line.

April 15 was China’s sixth National Security Education Day, an event marked by rallies and celebrations in both mainland China and, for the first time, Hong Kong, where police goose-stepped and children were encouraged to buy riot police stuffed toys.

Not everything about the campaign was so cuddly, however, with a graphic published in mainland state media warning people to be on the look out for foreign spies, including those who target university students and teachers, attempting to steal information or “incite defection.”

Academia has already come in for increased scrutiny under Xi, with student groups and outspoken professors being cracked down upon, while foreigners have found it harder to conduct research in China and even faced sanctions for publishing work critical of Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang.

This will likely only continue over the centennial year: in a piece on “historical nihilism” this week, historian David Ownby noted the phrase had been employed in the past “to condemn historians, scholars, anyone who dares to challenge orthodoxy, received wisdom, national myths,” warning it could be a prelude to further crackdowns on intellectuals and Party critics.

In a speech earlier this year, Xi warned that “hostile forces at home and abroad make use of the history of the Chinese revolution and the history of the new China, doing their utmost to attack, vilify and smear them, with the fundamental aim of … inciting the overthrow of the leadership of the Communist Party of China and our socialist system.”

And in a front page piece last week, the People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of the Communist Party, laid out a comprehensive propaganda campaign for the rest of the year leading up to the centennial, under the theme “Forever Following the Party.”

The campaign includes 80 new slogans, such as “Unity is strength, only with unity can we move forward” and “Closely uniting around the Central Party Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core, seizing a new victory in the comprehensive building of a modern socialist state.”

According to Hong Kong University’s China Media Project, the “top-down release of such slogans for broad national propaganda campaigns was unseen in post-reform China before 2019.”

Nor will the campaign be limited to the educational or political spheres: according to new guidance released this month by China’s National Radio and Television Administration – the country’s top cultural censor – “radio and television organizations at all levels should strengthen the Party’s overall leadership.”

Businesses too, even those which are nominally private, have also come under intense pressure to support the government’s line on Xinjiang and other issues, or face potential boycott or punishment.

Even Wen Jiabao, China’s former Premier, was censored this week when he published an essay about his late mother which contained what many saw as oblique criticism of the direction the country is going in under Xi.

Such criticism is growing ever more rare these days, as the Party prepares to celebrate its centenary with a show of absolute strength, lest anyone doubt that it will be around for another 100 years.