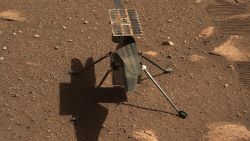

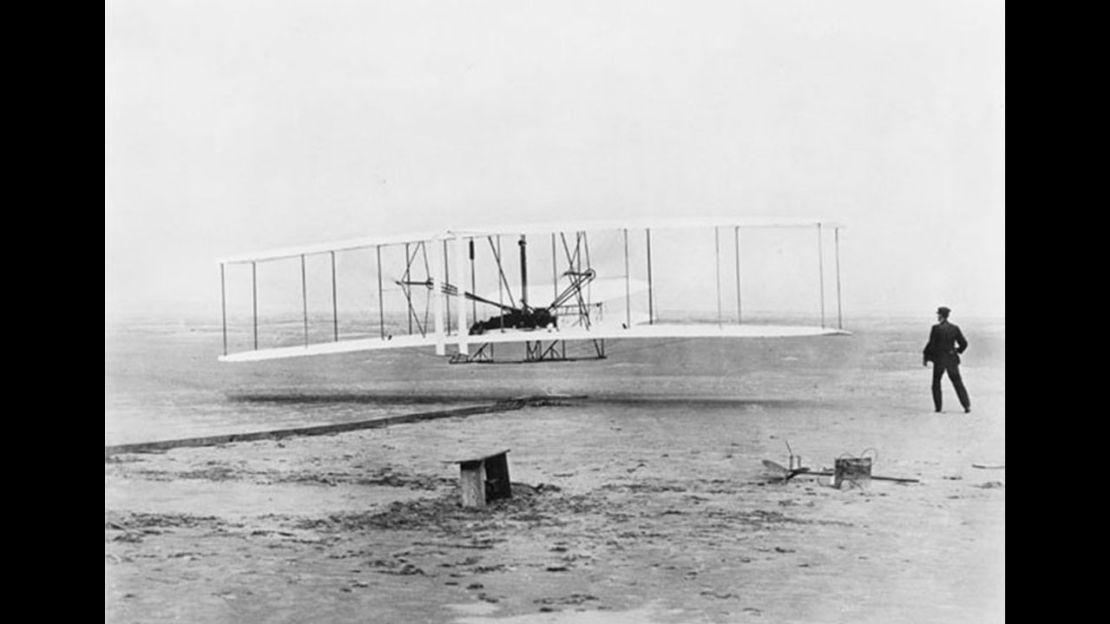

When the Ingenuity helicopter takes flight this month, it will be a Wright brothers moment on Mars. This first powered, controlled flight on another planet has been years in the making – and it has roots in the first such flight on Earth.

It has been 117 years since Orville Wright took flight in Flyer 1 for 12 seconds on a historic December day in 1903 at Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. In the image captured by John Daniels, a member of the US Life-Saving Station at the site, Orville’s brother Wilbur can be seen running alongside the aircraft. During the fourth and final flight that day, Wright achieved a nearly 60-second flight.

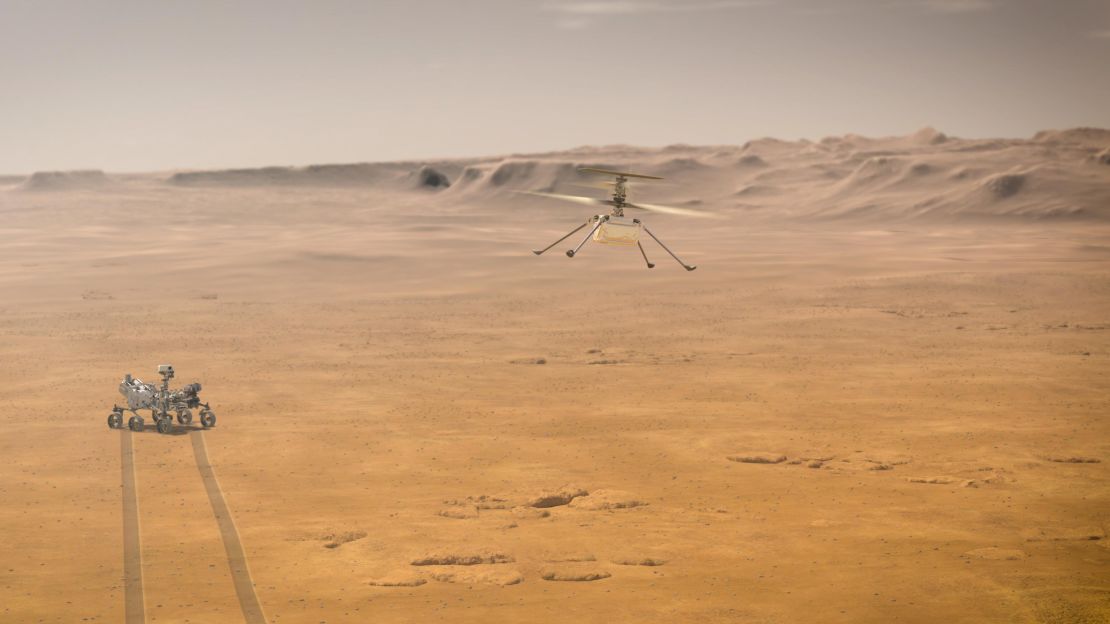

Millions of miles away and more than a century later, the 4-pound Ingenuity helicopter will use its two pairs of 4-foot (1.2-meter) blades to reach nearly 10 feet (3 meters) up through the thin Martian atmosphere. The miniscule helicopter will hover for 30 seconds, capture images, make a turn and return to the ground.

“The first flight is special. It’s by far the most important flight that we plan to do,” said Håvard Grip, Ingenuity’s chief pilot at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

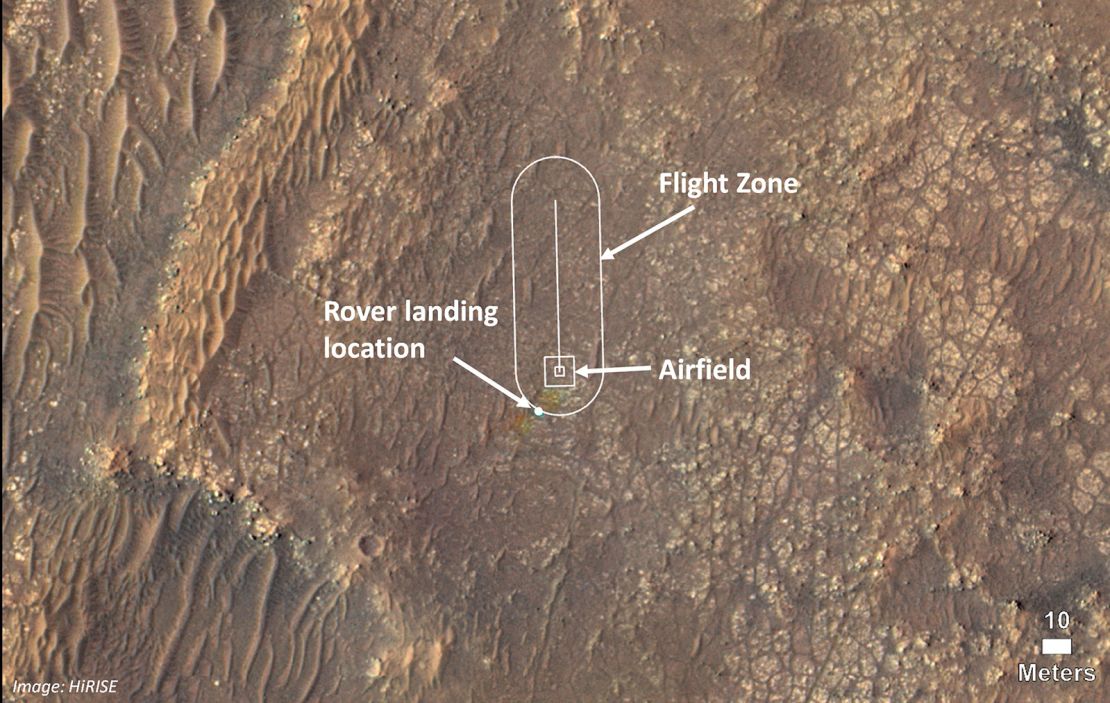

The Perseverance rover, which carried the helicopter to Mars, will watch from 197 feet (60 meters) away on an overlook called the rover observation location. The overlook is 3 feet (1 meter) higher than the flight zone.

“Think of it as a lookout point,” said Farah Alibay, Perseverance integration lead for Ingenuity at JPL. “If you ever go to a national park and you have a beautiful view, you want to park there and look. Our rover is going do that and our beautiful view is going to be Ingenuity, and we are going to do our very best to capture Ingenuity in flight.”

During Ingenuity’s maiden flight, Perseverance will attempt to take images and video. Ingenuity sounds like a small airplane taking off, and the rover’s microphones will try to capture that sound.

Images and data from the helicopter and rover will be sent back to Earth hours and then days later. That makes Perseverance the sole witness to this historic flight in the moment.

People around the world tuned in to watch Perseverance successfully land on Mars February 18 and see the unveiling of the first image shared by the rover after landing. But these historic moments don’t always play out on a global stage. Only five people witnessed the Wright brothers’ first flight.

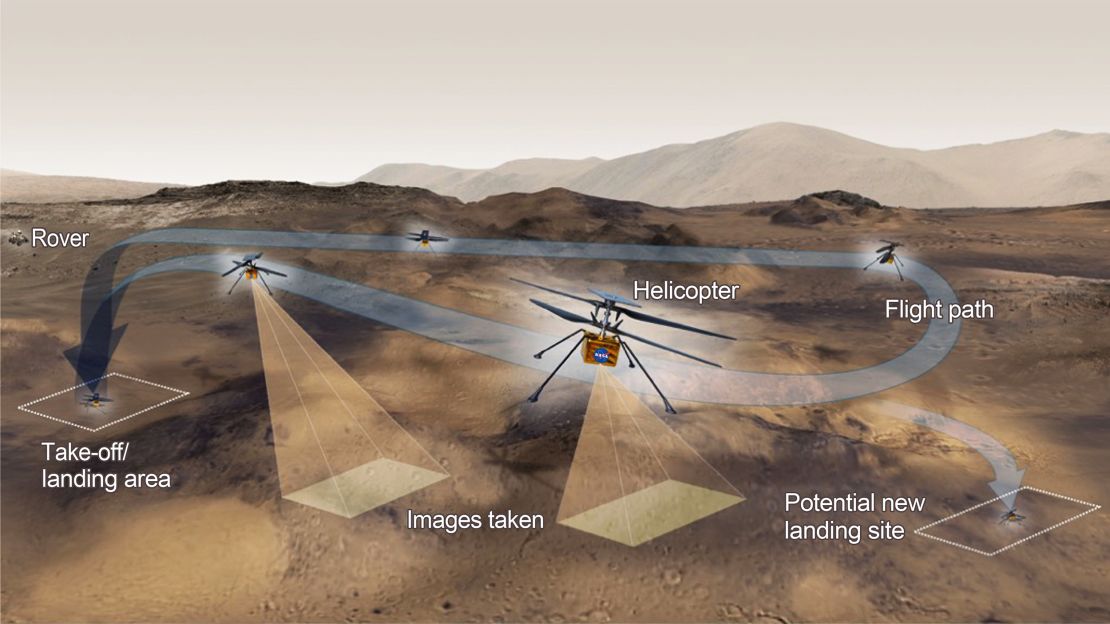

Ingenuity will conduct its first flight, and up to four others over the course of 31 Earth days, by itself, using a set of instructions sent from pilots at JPL. An onboard computer will use the images taken by the helicopter to track features on the ground and make tiny adjustments 500 times per second to keep the helicopter on its trajectory in case of disturbances like wind gusts.

If the first flight is successful, Ingenuity will push itself to fly higher and longer to test the limits of what it can do.

Experimental flight

The Perseverance rover will spend the next two years exploring Jezero Crater, the site of an ancient lake and river delta, for evidence of past microbial life and collecting samples that will be returned to Earth by future missions.

But April is Ingenuity’s time to shine. And once those 31 days are over, Ingenuity’s brief moment in the sun will end. Such is the life of a technology demonstration only designed to last for a short time.

The Wright brothers completed four successful flights on December 17, 1903, before a gust of wind toppled and destroyed Flyer 1.

The ephemeral nature of Ingenuity doesn’t matter to its creators. Technology experiments and demonstrations in the past are the reason that rovers like Perseverance can explore Mars today.

Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter:Sign up and explore the universe with weekly news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more

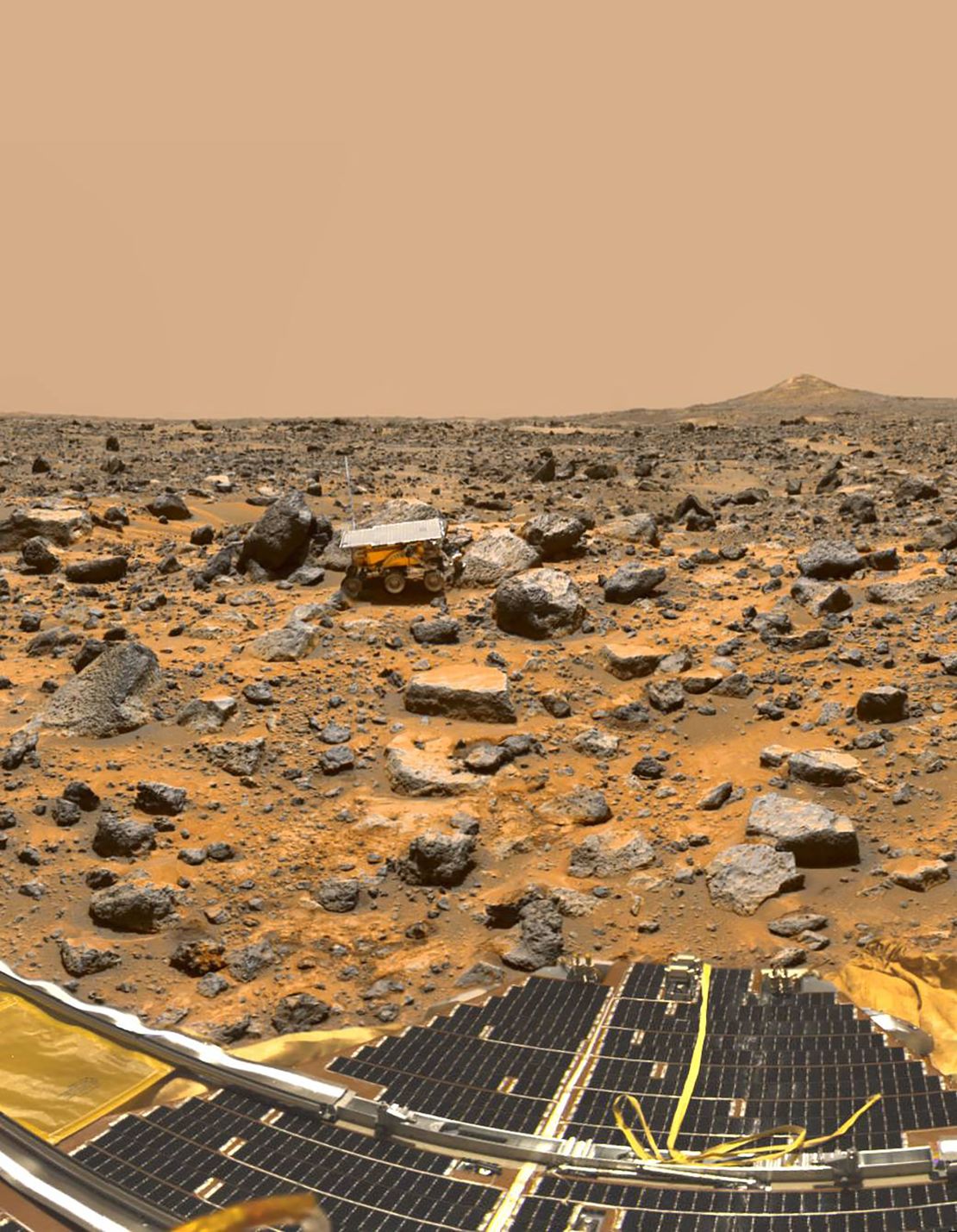

When NASA’s Pathfinder mission landed on Mars in 1997, it released a microwave-size rover called Sojourner on the surface. The technology demonstration was expected to last for seven days, but held on for 83. It took photos, explored the terrain of Mars and captured chemical and atmospheric measurements.

Perhaps most importantly, Sojourner demonstrated the successful use of the first wheeled rover vehicle on another planet.

“Sojourner paved the way for a new era of Mars exploration to redefine what we thought was possible on the surface of Mars and completely transformed our approach to how we explore there,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “That small rover enabled all the missions to follow, and now Perseverance, the size of a small car, is able to carry other technology demonstrations like Ingenuity, which will further expand our horizons.”

Sojourner demonstrated the value of surface mobility and the Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity and Perseverance rovers followed in its path – none of which were planned before Sojourner’s successful journey, said Bobby Braun, director for planetary science at JPL.

If Ingenuity is successful, it could lead to a similar evolution.

“I can only imagine where we may be a decade or so from now,” Braun said. “If we can scout and scientifically survey Mars from the air, with its thin atmosphere, we can certainly do the same in a number of other destinations across the solar system, like Titan or Venus. The future of powered flight in space exploration is solid and strong.”

The making of a Martian helicopter

The dream of Ingenuity began in the 1990s when JPL robotics technologist Bob Balaram heard Ilan Kroo, a Stanford University professor of aeronautics and astronautics, speak at a conference about a “mesicopter,” or a miniature airborne vehicle for Earth. Balaram could imagine it on Mars.

He proposed one for NASA during a call for submissions, but it wasn’t selected for funding. The Mars helicopter would sit on the shelf for 15 years as Balaram worked on other Mars missions.

Ingenuity’s time came in 2013 when Charles Elachi, director of JPL at the time, attended a presentation on drones and helicopters and returned to the lab asking if one could fly on Mars. Balaram retrieved his original proposal and developed the first conceptual design for the possibility of including it as a scientific instrument on the Mars 2020 rover – which would become Perseverance.

Ingenuity was passed over as an instrument for the rover – but it was funded and selected as a technology demonstration that would fly with the rover to Mars. Waiting all that time on the shelf was actually a good thing.

“We wouldn’t have been able to design something like this back in the 1990s when we didn’t have the computers and the battery technology,” said Balaram, chief engineer for the helicopter. “So actually the timing also was right in the sense that we needed some advances in technology.”

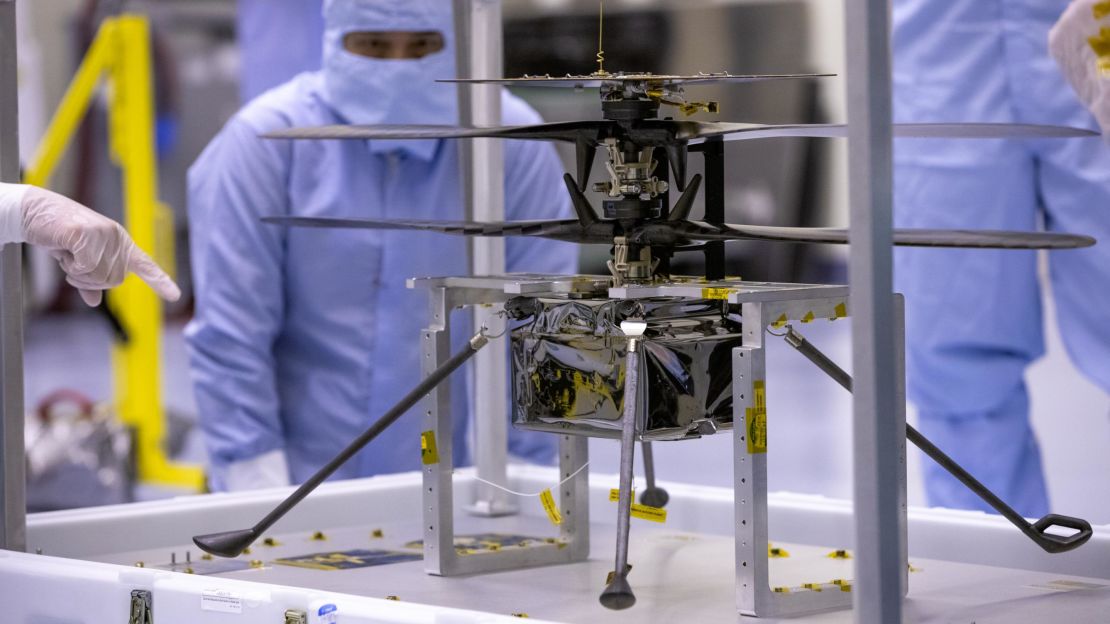

Then, it was time to build a brand-new type of vehicle that was both an aircraft and spacecraft – and one that wouldn’t endanger Perseverance in any way since the rover would be NASA’s first true astrobiology mission searching for signs of ancient life on another planet.

During the design phase, the team tested a small helicopter manually flown by a pilot in a Mars-like atmosphere. While the helicopter lifted, it wasn’t stable. Instead, it hopped around and crashed.

“What we learned from that is that the human reaction time is not sensitive enough to this helicopter because of how different the atmosphere is,” said Taryn Bailey, a mechanical engineer on the helicopter team at JPL. “So, after learning that the team looked into developing an autonomous flying helicopter.”

It needed to be lightweight to rise up through the thin Martian atmosphere, which is 1% of Earth’s atmosphere. But the helicopter also needed to include a solar panel, battery system, computer, radio, sensors and cameras in a flightworthy design that could survive launch and landing.

Testing the helicopter was another challenge because the test chamber needed to simulate Mars on Earth. Proof of flight was key before Ingenuity could go to Mars.

“There’s no textbook that says how to test a Mars helicopter, just like the Wright brothers didn’t have a textbook that said how to test gliders and powered flight vehicles,” Balaram said. “They had to invent it. So in the same way, we had to invent a lot of very unique testing capabilities.”

This involved the team building their own wind tunnel using 900 computer fans in a vacuum chamber to generate the winds Ingenuity may face on Mars.

The 25-foot (7.6-meter) thermal vacuum chamber controlled the temperature and pressure, allowing the team to test the helicopter flying through a Mars-like atmosphere, as well as a system that compensated for the difference in gravity between Earth and Mars.

It was a long seven years of design, building and testing, with a technical crisis or challenge arising every week, Balaram said.

The rigorous work put in to Ingenuity’s design and testing is what made the helicopter possible, and the current helicopter sitting on Mars went into fabrication in 2018, Bailey said.

The team pulled together people from specific disciplines, but they all thought outside of the box to help each other work on the components of the helicopter.

Bailey has been at JPL for five years and was invited to join the Mars helicopter team when she was 24.

“It means so much to be a part of this team and bear witness to this history making moment,” she said.

The helicopter and rover teams are eagerly awaiting the first flight, which could pave the way for helicopters and other rotorcraft that one day act as scouts for rovers and astronauts on Mars.

“It’s been a fantastic journey of discovery, exploration and working with fantastic people,” Balaram said. “And it’s not over yet.”