Cancer should be a near certainty for whales, the longest-living and largest mammals there are – but scientists are finding that cetaceans are excellent at protecting themselves against the deadly disease.

Just how do they do that? It could all come down to good genes, according to a new study published by The Royal Society.

“The odds of developing cancer increase with longevity and body mass,” explained lead study author Daniela Tejada-Martinez, a postdoctoral researcher at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Having more cells means having a higher probability that some of them may develop dangerous mutations as they grow and divide over the course of their life cycle.

“Paradoxically, big and/or long-lived species have lower cancer risk. However, the cetacean’s mechanisms against cancer and aging remain a mystery,” Tejada-Martinez said.

Her research, aimed at solving that mystery, suggests cetaceans could have evolved “additional mechanisms” to protect against such diseases like cancer, according to Tejada-Martinez.

Tejada-Martinez focused on this work as part of her doctoral thesis at the Universidad Austral de Chile. There, she combined her love of whales, her favorite animals since childhood, with her research interests.

“Cetaceans are an amazing model for ageing and disease resistance research, since they are the longest-living mammals. Some cetaceans, like the bowhead whale, can live over 200 years,” she said via email.

Genetic basis of disease resistance

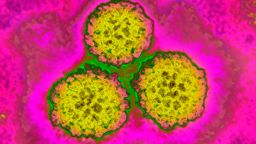

Specifically, the study investigates the evolution of tumor suppressor genes, or TSGs, in the ancestor of cetaceans, as well as in two main lineages: baleen whales (such as bowhead whales), and toothed whales (like orcas, belugas, dolphins, porpoises).

Tumor suppressing genes, Tejada-Martinez explained, are considered among the most important anti-cancer responses in the body, and are involved in hundreds of biological functions including DNA damage repair, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (a cell’s death).

“Cancer happens precisely when the TSGs are not working properly,” Tejada-Martinez said.

Scientists have identified more than a thousand tumor suppressing genes in humans, and we share 99% of them with whales, Tejada-Martinez explained via email.

The study shows that over the course of evolution in cetaceans, genes involved in the control of cancer onset and progression were positively selected. It also found cetaceans have a 2.4-times faster turnover rate of tumor suppressing genes than other mammals.

The high turnover rate, according to the research, is associated with gene duplications. Of the 71genes with duplications identified in cetaceans during the study, 11 are associated with longevity and the aging process, the researchers said.

According to Tejada-Martinez, the molecular variation observed in cetaceans – the faster gene turnover rate, the genes with positive selection and the gene duplications – could provide additional protection against molecular damage that can cause cancer.

This might even be responsible for the longer life spans and larger sizes of cetaceans like baleen whales, a finding she thought was most surprising.

From whales to humans

Understanding how whales protect themselves against cancer could help humans make strides against the disease, which killed an estimated 10 million people worldwide in 2020.

“Cancer is the original problem of multicellularity, and it is clear across numerous studies that nature has beat cancer in a myriad of ways in order to increase the fitness of organisms over the history of life,” said Marc Tollis, an assistant professor at Northern Arizona University.

“Since cancer is a body-size and age related disease, the search for whale-specific changes in protein coding genes that are linked to human cancers can help target potential human cancer therapies,” he explained.

Tollis previously researched the genomes of whales as connected to gigantism and cancer resistance, but was not involved with The Royal Society study.

Much more remains to be discovered about cancer resistance across species and the molecular mechanisms involved in it, but scientists are making strides.

“The study of medical conditions under an evolutionary perspective leads to a better understanding about how other species can fight diseases more efficiently than us,” Tejada-Martinez said.

“The discovery of new molecular variants, including additional copies of important regulatory genes, could lead to the creation of innovative treatments for cancer and age-related diseases,” she added.