Story highlights

This is the second feature of CNN's new series "History Refocused," surprising and personal stories from America's past that may bring new depth to the conflicts still raging today.

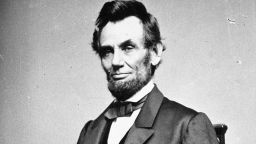

On April 11, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln delivered what would be his last speech from a window at the White House to the crowd below. They had gathered there expecting a celebratory speech on Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant just two days earlier.

But that evening, Lincoln’s speech was about Reconstruction, readmitting Louisiana into the Union and a proposal for “giving the benefit of public schools equally to Black and White, and empowering the Legislature to confer the elective franchise upon the colored man.”

Plantation-owning elites, Southern Democrats and White supremacists, however, would not easily concede political power to those who had so recently been their slaves. That evening among the crowd of listeners was an enraged John Wilkes Booth, who would go on to assassinate the President just three days later at Ford’s Theatre.

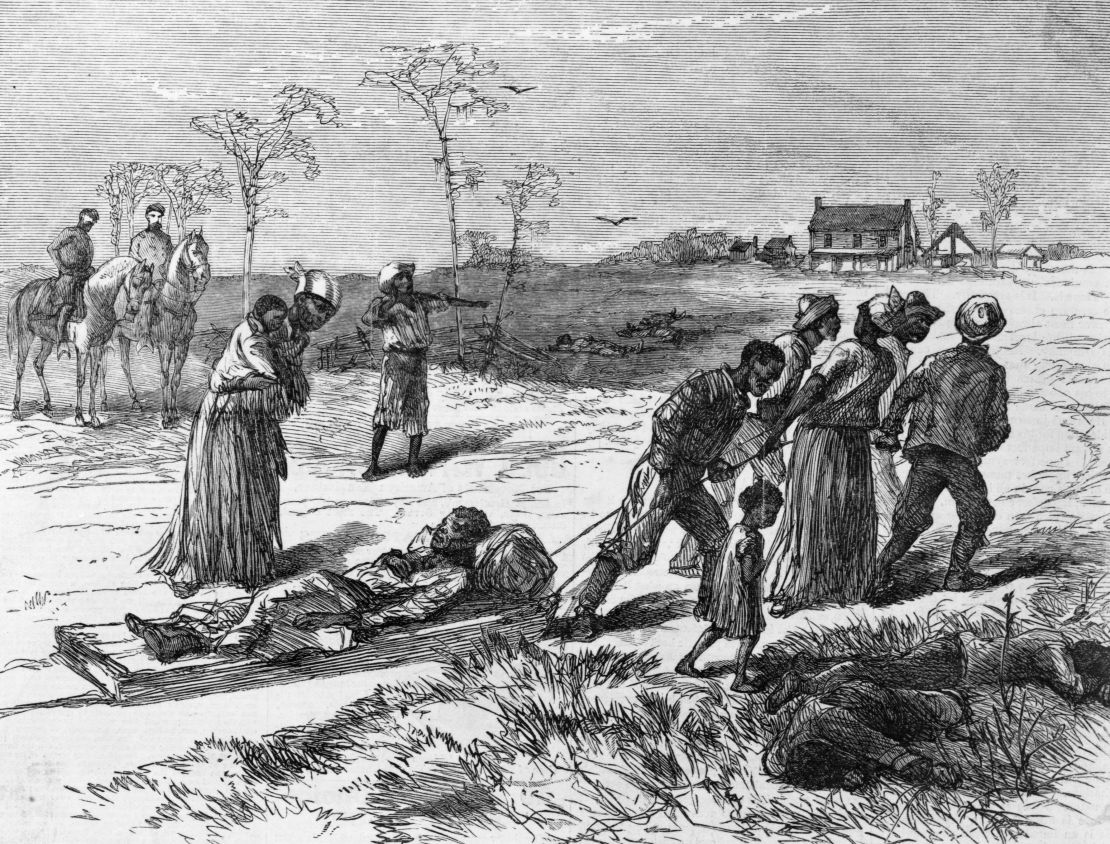

For decades after Lincoln’s death, White supremacists would wage a war of intimidation, murder and massacre on anyone, Black or White, who dared covet a share of their power. Yet, Black people persisted.

And between 1865 and 1880, over 1,500 Black men took political office; most not for long, as their efforts were cut down by mobs of violent White men.

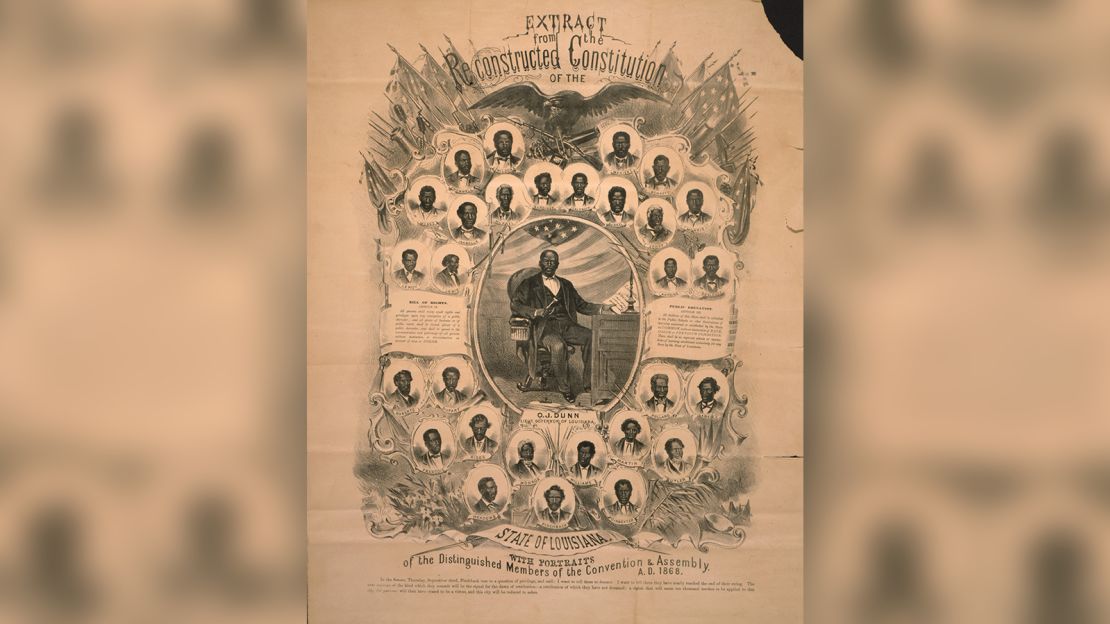

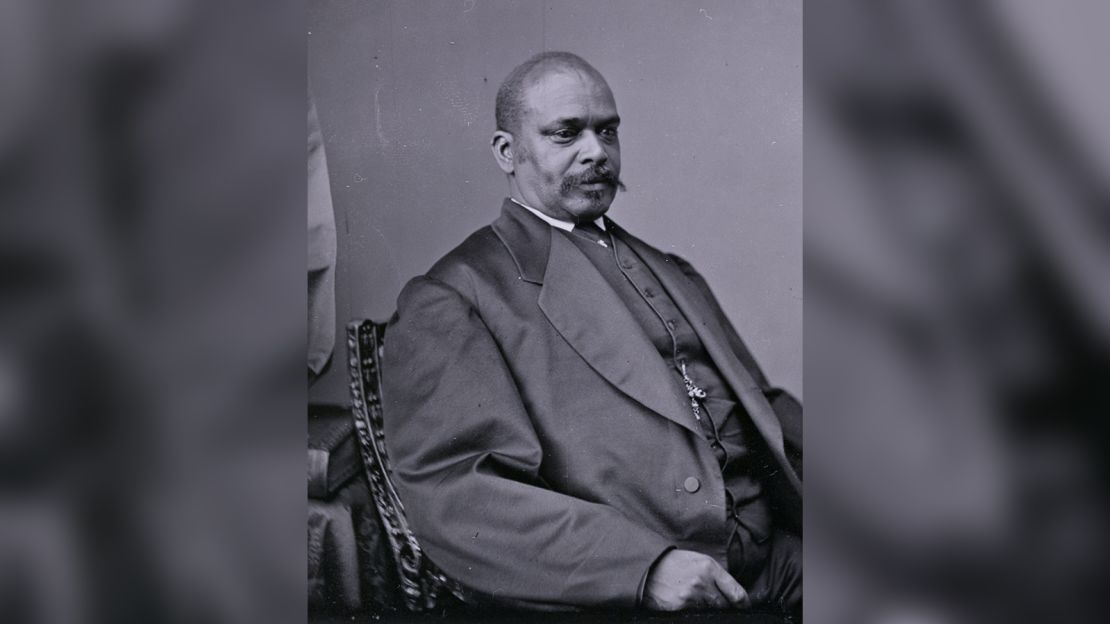

Oscar James Dunn was one of those determined men. He became the country’s first Black lieutenant governor in Louisiana in 1868 but died mysteriously in office only four years later.

For some experts, the 2021 Capitol riots are a present-day example and a legacy of the same kind of violent push back against the rise of Black men that Dunn and others experienced after the Civil War.

For the second story in our series, History Refocused, we spoke with historian Brian K. Mitchell, who spent years unearthing Dunn’s life – a passion ignited as a child after learning that he and Dunn were uniquely linked.

“Oscar Dunn’s story cannot explain the entire notion of Reconstruction,” Mitchell said. But “It does give students a very tangible person that they can wrap their minds around.”

One historian’s personal mission

As a history professor at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, Brian K. Mitchell dives deep into stories such as Dunn’s.

Mitchell remembers vividly the moment his elementary school teacher refused to acknowledge that a Black man had ever achieved real power in Louisiana.

One day in class, Mitchell’s hand shot up when the teacher asked if anyone had famous family members. He remembered his great-grandmother had once laid out newspaper clippings to tell him the story of his relative, Oscar James Dunn. His teacher was having none of it.

As a historian, Mitchell later saw her lapse of historical knowledge was common – the result of a successful campaign to rewrite everything that happened during the Civil War and after.

“I was taught that Reconstruction was a failed attempt, that it was awful and that the Black leadership that came in was totally inept,” said Mitchell. “That is totally untrue.”

Dunn was born a slave and set free in 1832 by his future stepfather. He grew up to be bright and educated, trying his hand at teaching music and masonry. He became a leader among the Freemasons and saw an opportunity to use his skills during the Civil War.

Dunn knew businessmen and plantation owners still needed workers. So he started an employment agency, connecting the newly freed men and women with jobs and keeping them from getting cheated. He was wildly successful.

“Oscar James Dunn is the personification of African American hope and African American values in the United States,” said Mitchell. “Throughout his whole life, he’s always learning.”

In the mid-1860s, Dunn joined a group of elite Black, colored and Afro-Creoles in Louisiana, then a hard-line racist state, who had economic status but yearned for more political power. In 1865, he and others formed a group called the “Friends of Universal Suffrage,” sending delegates to lobby Lincoln and his Republican party to show them just how much support they would get if they allowed Black men in the South to vote.

Lincoln supported the vote for these educated Black men and for former soldiers, but neither he nor his Republican Party advocated for universal suffrage. After Lincoln’s death, historian Kate Masur said support grew, but only to a point.

“Some of these White Republicans would have thought African Americans deserve to be free,” said Masur. “But voting? That seems like a bridge too far.”

It would take years of unrest before crushing violence changed their minds.

When White supremacy turns into a movement

In late 1865, President Andrew Johnson declared national unity and quickly folded Southern states back into the Union. Johnson often clashed with his Republican Congress, for it believed only a strong hand could deal with the emboldened former Confederates still running things at the local level.

While Freedman’s Bureau workers empowered former slaves through education and resettlement, Southern states passed “Black codes” restricting their rights. Black people were entrapped into work contracts, arrested for carrying guns and forced to watch their children taken away and “apprenticed” to Whites.

White Supremacist groups formally organize; the Ku Klux Klan held its first meeting that December in Pulaski, Tennessee, and the Knights of the White Camelia form two years later.

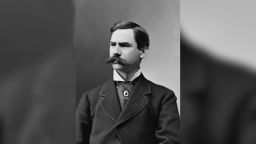

In July of 1866, 25 Louisiana Radical Republicans held a meeting in support of voting rights for freedmen at the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans.Tensions in the South were rising – one month earlier, dozens of Black people had been killed by White rioters in Memphis with little repercussion – and Dunn was warned not to go.

In New Orleans, hundreds of Black supporters paraded toward the Institute. They were soon surrounded and attacked by an angry White mob – many of them police officers – and dozens were killed. But Dunn had stayed away and was safe. He later testified in front of a Congressional Committee sent from Washington, who concluded that ex-Confederates in the local government were to blame for inciting the attack.

The violence was enough to push Congress to act. They overrode a veto from President Johnson and passed the first of several Reconstruction Acts in 1867. The Act broke the South into districts and put federal military generals in charge, weakening the hold of Confederate sympathizers.

Gen. Philip Henry Sheridan, who was in command in Louisiana, appointed Dunn to the City Council and Dunn became the new “assistant recorder,” or what Mitchell calls a sort of “mini-mayor.” His job included overseeing cases in the same courtrooms where, a few years earlier, Black people had no right to defend themselves. Dunn was fair, trusted by Black and White, and positioned himself perfectly for when Black people were finally allowed to take part in new elections.

“The Black vote today would not even come close to the proportion of eligible voters who are going to the polls in the late 1860s and early ’70s,” said Mitchell of the swell of Black freedmen showing up across the South to cast ballots.

Dunn’s moment comes

On July 11, 1868, Dunn became lieutenant governor of Louisiana, serving under Henry Clay Warmoth on the Republican ticket. Dunn’s first legislative address showed hope and restraint:

“As to myself and my people, we are not seeking social equality. That is a thing no law can govern,” said Dunn. “We simply ask to be allowed an equal chance in the race of life.”

Not two months later, hundreds of Black men, women and children would be massacred by more White mobs in St. Landry Parish, New Orleans. The anger of White Southern Democrats seethed and boiled up over the new elections.

Before the War, society in the South had been defined by social class, and sitting comfortably at the top were White plantation owners, who did not work. Relegating labor to lesser people defined who you were as a successful White Southerner. When that free labor was taken away, so too was the very question of what defined Whiteness – if you’re laboring like Blacks, what separates you from them?

White Democrat leaders had thought they could cobble together racist laws and cling to webs of social codes to keep Blacks subjugated, but they came to believe all would be lost if Blacks and Republicans used the power of the vote to dismantle their rules.

“The heart of Louisiana was big slave plantations and most Whites in Louisiana were deeply committed to White supremacy,” said Eric Foner, an expert in Lincoln and Louisiana history.

Those who weren’t deeply committed to White Supremacy would soon find themselves under pressure. Many lower-class Whites had grown used to working beside Blacks, but middle and upper-class Whites perpetuated the idea of Whiteness as “anti-Blackness.”

Whites were often outnumbered by Blacks in many Southern areas, and feared unfounded and irrational threats dreamed up by powerful, partisan local newspapers. The idea of using violence to keep Whites safely in power became a social craze that soaked through communities and, as historians argue, never truly dried out.

Foner made a comparison to the January 6 mob attack.

“You know, we recently saw a mob of White supremacists assaulting the Capitol building in order to overturn an election, and people on TV always said this is unprecedented,” said Foner. “Unfortunately, it’s not unprecedented. It’s what’s happened to Louisiana a number of times in Reconstruction.”

Howard University historian Edna Greene Medford echoed that statement, but also pointed to what happened in Georgia that same day – Black organizers driving voters to elect a Jewish senator and a Black senator. Sen. Raphael G. Warnock is only the country’s 11th Black US senator to serve.

“If Black people didn’t vote, you wouldn’t see this violence,” said Medford. “It’s people wielding political power and others feeling that they’re losing the vote they always had.”

“What does this permanent shift mean to a class of people who always held political power and have always held economic power?” said Mitchell. “What does this mean for White America if it has to share this notion of who has the right to rule?”

The 15th Amendment, which aimed to protect the vote, was ratified in 1870, just as White Northerners grew tired of the costly military occupation of the South. The generals, armies and the Freedman’s Bureau slowly withdrew, leaving men like Oscar Dunn exposed.

Dunn’s star burns bright then fades

In 1869, Dunn embarked on an ambitious train trip from New Orleans to Boston hoping to meet with abolitionists, senators and state leaders. He’s welcomed by some but shunned by others. He’s refused service at White hotels and moved to segregated train cars, and realized none of the Civil Rights laws passed by Congress could begin to fight the racism so deeply rooted throughout the country – South to North.

But when he visited Washington after President Ulysses S. Grant’s inauguration, he was invited by the President to the White House – the first-ever invitation for an elected African American official.

Dunn was above reproach, he didn’t drink or smoke and he shunned bribes. His work addressed the plights of Blacks, but also that of poor White families, long-suffering under a society controlled by planter elites.

“Both Democrats and Republicans, conservatives and radicals, saw in Dunn a pragmatism and fairness that he always tried to do the right thing by everyone,” Mitchell said. “And many times this will come back to bite him.”

In 1871, Louisiana Gov. Warmoth injured himself so badly in a boataccident that Dunn took over his gubernatorial duties, against his wishes. He’s believed to be the first Black man to do so.

Warmoth had been losing popularity, was accused of corruption and began distancing himself from the freedmen he had promised to support. Warmoth and Dunn were at odds – he didn’t like to see Dunn so easily acting as his substitute.

Mitchell describes Oscar James Dunn’s final days as suspicious; one night after a dinner, Dunn fell violently ill. His friends believed he’d been poisoned. He died quickly afterward at the age of 45, just shy of completing his full four-year-term. Mitchell says it’s later revealed that he’d been on Grant’s list of possible vice presidential picks.

Tens of thousands attended his funeral. Warmoth was later removed from office, eventually making way for P.B.S. Pinchback, who would briefly become Louisiana’s first Black governor.

A monument was planned in 1873 in Dunn’s honor but was never built. The “Lost Cause” narrative took over and the accomplishments of Black leaders during Reconstruction were whitewashed, erased from Southern textbooks and vilified by movies, such as “Birth of a Nation,” which made Black congressional leaders look unintelligent and incompetent.

“If we’re going to say that the reason that Reconstruction was a failure was the ineptitude of Black politicians, Dunn was the model politician,” said Mitchell. “He was generous. He was kind. He was honest. And that is not the value set in history that they want to record.”

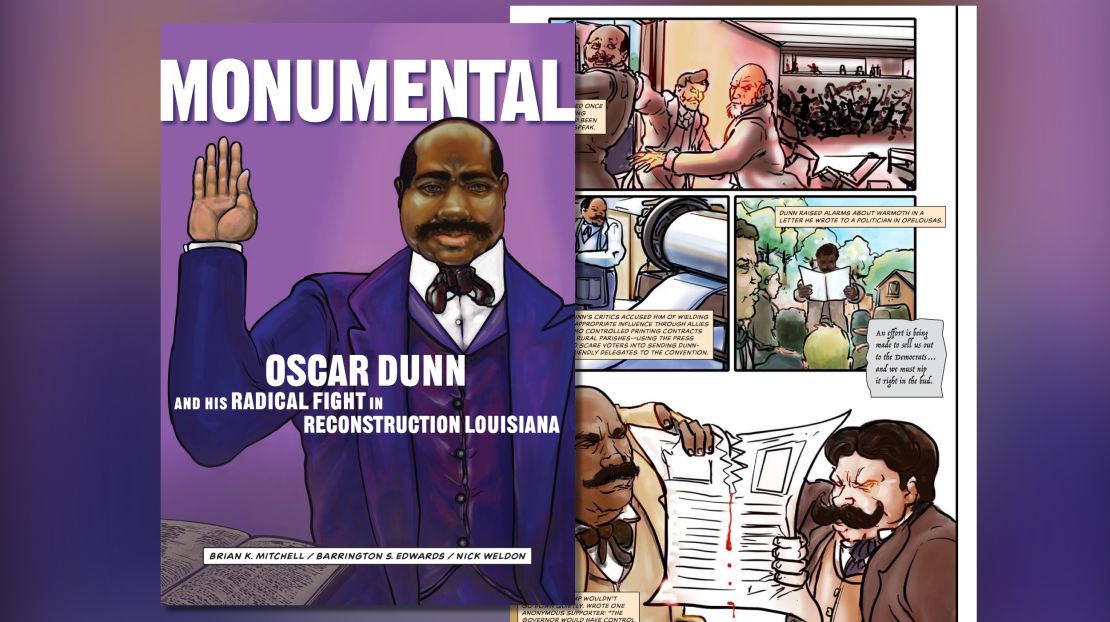

But history has new storytellers.

As Confederate statues come down, Mitchell hopes men like Oscar James Dunn can replace them, putting them back in the spotlight. The National Park Service is reworking its entire messaging on Reconstruction with help from historians like Kate Masur, and a new National Reconstruction monument is now in Beaufort, South Carolina.

But it is Mitchell’s work on Dunn that revives his ancestor most vividly. He’s turned Dunn into a superhero for a graphic novel he co-wrote called, Monumental, putting a Black person as one of the real stars of the country’s evolving legacy.

“I want children to know that they can be anyone that they choose to be and historically they have played a part in every facet of American history,” said Mitchell. “They are just as important to the American narrative as anyone else.”

For more on the life of the 16th president, watch CNN’s Original Series “Lincoln: Divided We Stand” Sundays at 10 p.m. ET/PT.