The streets of Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon, appeared outwardly calm Tuesday morning, as residents made their way to work a day after the military detained Aung San Suu Kyi and other democratically-elected leaders and seized control of the country.

But behind the business-as-usual facade, anxiety is growing among many as to what will come next. Memories of living under the brutal military rule of the past are seared into the minds and bodies of many Burmese people. Critics, activists, journalists, academics and artists were routinely jailed and tortured during nearly 50 years of isolationist rule.

There are now fears that Monday’s actions could be a prelude to a wider clampdown. In all, the new ruling junta removed 24 minsters and deputies from government over allegations of election fraud and named 11 of its own allies as replacements who will assume their roles in a new administration.

On Tuesday, Health Minister Myint Htwe also announced on Facebook that he was leaving his post “as per the evolving situation.”

Questions as to the exact whereabouts of, and who is in communication with, senior members of the formerly ruling National League for Democracy (NLD), including recently deposed State Counsellor Suu Kyi, remain unclear.

One member of parliament (MP), who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals, told CNN by phone on Tuesday that around 400 MPs are being detained in a large guesthouse in Naypiydaw.

The MP described the guesthouse as a large compound where detainees are able to roam freely, but are prohibited from leaving by military guards patrolling the gates.

He also said that, so far, the detained politicians are not trying to negotiate their release and do not know what will happen to them.

In a statement Tuesday, the NLD called for the immediate release of those detained, including recently deposed President Win Myint and Suu Kyi, and to allow the country’s third parliament to govern.

It also called for the recognition of November’s general election results and said the coup was “a defamatory act against the history” of Myanmar and its government.

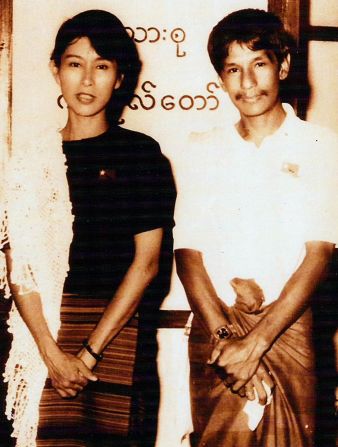

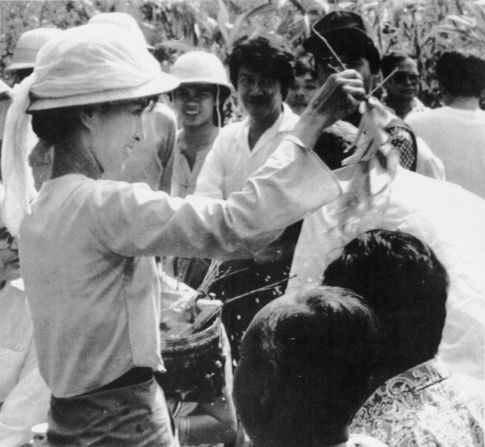

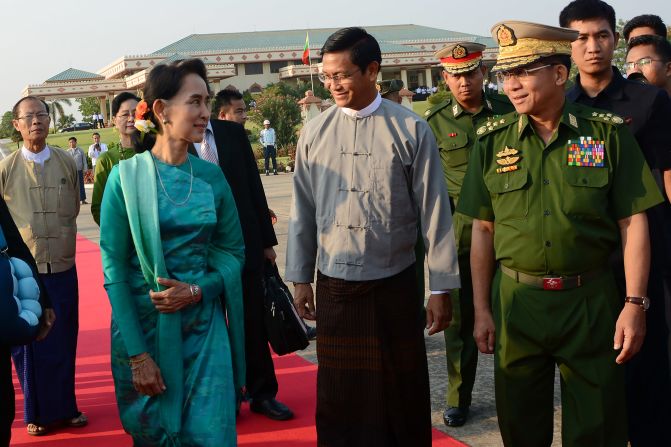

In pictures: Aung San Suu Kyi

In Naypyidaw Tuesday, though most businesses had reopened, a heavier security presence remained. Tanks were seen at the gates of parliament, and soldiers were standing guard outside a government guesthouse where some politicians who were detained in the coup said they were being held.

While communications across the country remained spotty with intermittent connections on phone and data, banks had reopened, according to state-run newspaper Global New Light of Myanmar. In Yangon, residents could be seen queuing to get cash out at ATMs.

NLD spokesperson Kyi Toe late Monday said on his personal Facebook page that Suu Kyi was being held at her official residence, where she was “feeling well” and “walking in the compound frequently.”

A statement purportedly from the de facto leader was published on her party’s official Facebook account Monday, calling for people to protest against the coup, though there were questions about the statement’s authenticity.

“The actions of the military are actions to put the country back under a dictatorship,” the statement said.

Suu Kyi has not been seen since she was detained early on Monday morning. The statement ends with her name but is not signed, and it was unclear how Suu Kyi would issue a statement while in detention.

Analysts warned that social media accounts could have been hacked or taken over by bad actors in order to encourage actions that might provide a pretext for further military force.

The only demonstrations seen so far have been small-scale and from pro-military supporters.Suu Kyi, however, remains enormously popular, especially among the country’s majority Bamar ethnic group.

Doctors working in hospitals across Myanmar have pledged to go on strike from Wednesday to protest the coup.

The Assistant Doctors group at Yangon General Hospital released a statement on Tuesday saying it would take part in the “civil disobedience movement.”

The doctors say they will not work under a military-led government and called for Suu Kyi and Myint to be released.

Though her supporters have yet to take to the streets, many in Yangon have privately expressed anger over the military’s actions,which they said disregarded the will of the people in what was considered to be a generally fair election.

Some have also questioned why the military would take over when they benefited from the previous legislative arrangement. The military, or Tatmadaw, as they are officially known, were constitutionally guaranteed 25% of seats in parliament and control over powerful ministries.

One Yangon-based reporter said he spent a sleepless night worrying about whether he would get a knock on the door and was scared that journalists would be targeted next.

“All the people now realize what the military are capable of. This is who they are and this is how they rule. You cant underestimate them. All Burmese people understand now, that, OK, this is the real situation – the past five years, the freedom we got, is nothing,” said the reporter, who didn’t give his name due to the potential dangers.

Disastrous economic and socialist policies under dictator General Ne Win had plunged the country into poverty and a mass popular uprising against his regime in 1988 was brutally put down by the military. Another coup in September that year installed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), and during its rule, thousands of people including democracy leaders, activists and journalists were imprisoned for decades.

Others fled into exile abroad or went to the jungles and took up arms against the military government as part of a student army (ABSDF).

“We’ve got trauma. Nobody wants to get shot, flee the country, join in the jungle like the ABSDF did before. Nobody wants that situation again,” said the Yangon reporter.

News of the coup, he said, was like history repeating itself. He remembers listening to the radio when his dad was arrested and spent 10 years in jail on political charges when he was 3 years old.

“All the things happened during those 36 years, history is repeating. The cycle is repeating. Nothing is new, nothing is strange. It is the same,” he said.

The United Nations Security Council is set to hold an emergency meeting Tuesday, with UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres saying the events were a “serious blow to democratic reforms.”

UN special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar Tom Andrews on Monday called for the imposition of sanctions and an arms embargo on the country.

“Now, more than ever, we must act,” he said on his official Twitter account.

The unfolding situation in Myanmar is also a big test for US President Joe Biden, who called on Myanmar’s military leaders to relinquish power and threatened to review sanctions on the country.

The United States removed sanctions on Myanmar over the past decade based on progress toward democracy. “The reversal of that progress will necessitate an immediate review of our sanction laws and authorities, followed by appropriate action,” Biden said in a statement.

There is evidence that the uncertainty over what’s to come in the immediate aftermath of the coup is having an impact on international business.

On Tuesday, Japan’s Suzuki Motor Corporation announced it has stopped production at its two factories in Myanmar to secure the safety of its workers following the coup. About 400 people work in the factories and the company’s public relations officer Mitsuru Mizutani said they will restart when the security of their workers is ensured, though they do not know when that will be.

Additional reporting from journalist Chie Kobayashi in Tokyo. CNN’s Kocha Olarn reported from Bangkok.