President Donald Trump ignited a months-long political battle in 2017 when he appointed Jim Bridenstine, a Republican congressman from Oklahoma, to run NASA.

The space agency is typically helmed by a scientist, a former astronaut or an otherwise publicly apolitical figure, and many lawmakers, space fans and stakeholders feared that Bridenstine’s appointment could irrevocably politicize NASA and its efforts to return humans to the Moon and conduct climate research.

Even some Republican senators initially refused to back his appointment,with Florida’s Marco Rubio going so far as to say Bridentine’s appointment could be “devastating” for NASA. But Bridenstine was eventually confirmed by the Senate in April 2018, more than seven months after his appointment, in a 50-49 party-line vote after Jeff Flake of Arizona dramatically switched his vote in the final hour.

Over the past two years on the job, Bridenstine has repeatedly sought to position himself as a bipartisan leader, and he’s managed to gain broad respect from the space community. Many stakeholders also say his political experience has been a bonus, allowing him to better promote NASA’s interests on Capital Hill.

Several analysts and experts told CNN Business that, in their view, Bridenstine has done a good job navigating a very complex situation — balancing the need to carry out the desires of his boss, the President, while also attempting to keep NASA out of the hyper-partisan political fray.

Money for the moon

Perhaps the largest piece of space news to land in the past four years was the Trump administration’s shock announcement in 2019 that the United States would return astronauts to the Moon within five years. The declaration, made by Vice President Mike Pence at a National Space Council meeting, was so unexpected that even some NASA employees were surprised. Bridenstine told CNN last year that he had prior knowledge of the announcement, but only a month earlier, in February 2019, NASA was still touting its goal of landing on the moon by 2028.

Because 2024 would be the last year of Trump’s presidency if he’s elected to another term, the plan to drastically accelerate NASA’s Moon landing plans was largely viewed as political. And it was left up to Bridenstine to rally bipartisan support for the mission and convince Congress to fund the program, which is expected to cost $30 billion or more on top of the space agency’s $20 billion annual budget.

So far, lawmakers haven’t been willing to fork over the cash NASA has requested.

“He has tried and tried and tried to convince Congress that there is a legitimate reason for having a deadline of humans landing on the moon by 2024,” said Laura Seward Forczyk, the founder of space policy and consulting firm Astralytical. “So far, he has not been able to.”

Part of the issue is that, for two years, Congress had been asking for a detailed breakdown of the budget NASA would need, but until recently, the space agency could only provide ballpark estimates, Forczyk said.

But even though the funds aren’t flooding in yet, and even ifthe 2024 deadline does prove to be unrealistic, Bridenstine’s NASA has spent the past two years laying out a plan for how the space agency will get humans back to the moon — and that plan has won plenty of supporters and critics.

Commercializing space

The latest iteration of NASA’s moon ambitions, dubbed the Artemis program, has been touted as far more than a one-off novelty mission: Bridenstine and Pence have repeatedly said the next lunar landing will be done with the goal of creating a “sustained presence” on the moon, paving the way for astronauts to keep going back again and again. Eventually, they say, people could be living and working on the moon, collecting lunar ice for rocket fuel or researching the lunar environment, and preparing to extend a human presence to Mars.

But right now, most of the technology needed to accomplish the first Artemis lunar landing does not exist. Notably, NASA still needs a lunar lander, which is the vehicle that would shuttle astronauts from their spacecraft down to the Moon’s surface. Worse, the current plan for how NASA will develop that technology does not have broad support.

Rather than handling design and development of the lunar lander in-house, Bridenstine is pushing for commercial companies to design their own lunar landers, with funding help from NASA. And while the companies will technically own the final vehicles, NASA can have its pick of which lunar lander to use for the Artemis program.

It’s an idea that builds off of NASA’s other flagship program, the Commercial Crew initiative, which turned NASA’s traditional launch program on its head. Instead of developing the rockets and spacecraft in-house, as the agency had done from the original Mercury rocket program of the early 1960s until the retirement of the Space Shuttle, NASA contracted virtually everything out to private corporations, providing only the astronauts. Essentially, NASA merely bought tickets for the flight, though taxpayers funded the bulk of the new spacecraft’s development costs.

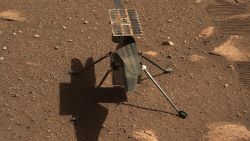

That program started under President Barack Obama as an effort to develop a cost-efficient way to transport astronauts to and from the International Space Station. The Commercial Crew Program reached its its climax earlier this year, when SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft carried two NASA astronauts to the ISS and back.

Some members of Congress, however, are hesitant to deem the Commercial Crew program the best blueprint for creating a lunar lander. A bipartisan bill in the House has called for NASA to keep full ownership of the lunar lander used for the Artemis program, noting that will give the public “unfettered insight” into how taxpayer dollars are being spent.

Democrats expressed their dismay when, earlier this year, Bridenstine moved forward with plans to keep the lunar lander a commercial endeavor. He awarded nearly a billion dollars to Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Alabama-based Dynetics, queuing each of them up to design and develop their own lunar landers and compete with each other for NASA contracts.

More recently, lawmakers have also pushed back on NASA’s lack of transparency about the program.

Even if Bridenstine hasn’t won over Congress, however, Forczyk views the Commercial Crew contracting style as a huge win that saves money and leads to the creation of exciting new technologies. And she applauds Bridenstine’s decision to stick with that model.

“I’m a card-carrying, pin-holding member of the Bridenstine fan club,” she said. Overall, she gives his two years at the helm of NASA an “A-“.

The ISS and International collaboration

The International Space Station has for 20 years hosted astronauts from NASA and dozens of other partner countries, serving as a physical hallmark of global collaboration in space.

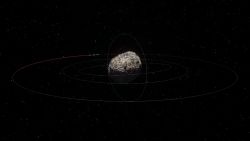

But the football-field-size orbiting laboratory won’t last forever. It’s currently scheduled to end service in 2024, though that could be extended to 2028. And Bridenstine’s plan to slowly ease operation of the space station over to the private sector has received pushback from Congress, and it’s spurred some debate in the space community about just how much corporate branding and private interest the future of spaceflight should entail.

Public opinion polls show Americans are excited about commercial companies exploring space, but they’re also skeptical of the idea that NASA should take a back seat.

The space station’s pending retirement also raised big questions about how the United States will continue its partnerships with other spacefaring nations.

“The ISS has been the primary mechanism for NASA’s international collaboration,” said Brian Weeden, the director of program planning for the nonprofit Secure World Foundation, which promotes cooperative space exploration. “And there was a lot of questions over what comes next” after the station ends service.

But Bridenstine did a “great job” of solidifying the Artemis program as one that will be internationally collaborative. Japan and the European Space Agency have already signed on as partners who will help build necessary hardware. And seven countries besides the United States have signed onto NASA’s Artemis Accords, which Bridenstine announced as a set of principles for putting humans back on the moon that includes permitting commercial companies to mine and sell rewsources in space.

Weeden said the documents were a step in the right direction, ensuring that a fast-paced return to the Moon wouldn’t happen without carefully thought out rules of the road. But the document is still very contentious in international law.

Countries that have a tense Earthly relationship with the United States have not signed on to NASA’s Artemis plan.

The head of Russia’s space agency has criticized the program for being “US-centric.” And, Weeden said, “the single biggest glaring hole is engaging with China.”

Weeden said he recognizes that Bridenstine’s ability to engage directly with China on space exploration is hampered by hawkish language in American laws. But it is something, Weeden said, that the US should pursue if its goal is to keep space exploration a collaborative and peaceful endeavor.

Still, overall, Weeden said he believes NASA under Bridenstine has been moving in a great direction. And it’s worth noting, he added, that many of the policies are a continuation of space policies implemented by previous administrations.