For Ha Sze-yuen, the sea surrounding Hong Kong is more than just a backdrop for sunsets and beaches.

The 73-year old views the ocean as his route to freedom - a means of escape from the oppression and poverty of communist China.

On the night of April 16, 1975, Ha and a friend slipped past Chinese border guards and plunged their homemade, inflatable rubber dinghy into the dark water of Shenzhen Bay.

They then started paddling toward the bright lights of Hong Kong, which at the time was still a British colony.

Ha said he had already been caught and jailed three times during previous failed attempts to swim across the water. After the third attempt, he said, guards beat him so badly his mother cried when she saw his wounds.

“I was fighting for my freedom,” Ha said. “I was afraid, but compared to life in China the fear was nothing.”

Ha said he and his mother, a school teacher, were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, a period of political chaos and violence unleashed by Mao Zedong, due in part to the fact his father had been a Kuomintang military officer who fled Communist rule after his side lost the Chinese civil war.

During the worst decades of Mao’s rule, thousands of Chinese fled south into Hong Kong.

In photos taken after Ha’s final, successful attempt to make it to the city, the beaming 28-year-old stands looking over Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbor, dressed in bell-bottom trousers and a fashionable striped shirt.

But 45 years later, Ha no longer sees this historic port city as a sanctuary.

“Now I feel like freedom is being taken away gradually,” he said, referring to an ongoing crackdown on political opposition in the city by the government and Chinese authorities, who recently imposed a national security law on Hong Kong, which has further limited space for dissent and left many activists fearing arrest.

The arrests of close to 10,000 anti-government protesters over the past year and the increasing targeting of opposition politicians and activists have created a phenomenon that would have been considered unimaginable to many just a few years ago.

Some Hong Kongers are now taking great risks to flee the city, even choosing to try to smuggle themselves out by sea.

Motorboat to Taiwan

Flies buzz around rabbitfish drying in the sun on a concrete pier emerging from the sleepy fishing village of Po Toi O.

This was the origin point for an ultimately failed escape attempt from Hong Kong that began one evening in August.

Several villagers – none of whom want to be named to avoid possible reprisals – said they saw a group of people loading fuel onto an open speedboat equipped with three outboard motors. The group then set out from the pier around sunset.

A resident, who also asked not to be named, said the group made a mistake leaving after sunset, when there is not much activity on the water. He pointed out that smugglers, moving everything from frozen meat to people between Hong Kong and mainland China, typically operate in the light of day, when crowds of pleasure boats and fishermen provide better cover from authorities.

Several days after the conspicuous departure from Po Toi O, the Coast Guard in China’s coastal Guangdong province made an unusual announcement that its officers “seized a speedboat suspected of illegally crossing the sea border.” Guangdong authorities provided coordinates for the seizure, roughly 50 kilometers (31 miles) off the eastern coast of Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong government later confirmed that “12 local men and women aged between 16 and 33” had been arrested and were now in the custody of Chinese law enforcement. Shenzhen Yantian Police confirmed Sunday that the 12 have been placed under criminal detention for “illegal border crossing” and their legal rights are “protected by the police according to laws.”

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a statement on Friday that he was “deeply concerned” that the group has been denied access to their lawyers, and called on the authorities to “ensure due process.” In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying tweeted that the 12 were “not democratic activists, but elements attempting to separate Hong Kong from China.”

Court documents reveal most of the 12 arrested were facing charges in Hong Kong for alleged crimes such as arson, possession of firearms and rioting. One of the group had been arrested under the national security law imposed on the city by Beijing on June 30.

‘I don’t even know if he is dead or alive’

The families of the detainees gave an emotional press conference in Hong Kong on Saturday, calling for the Chinese authorities to transfer their relatives back to Hong Kong, to allow calls to the families and access to lawyers, and to provide necessary medication.

“I can’t sleep every day, I am very worried. Worried that (there is) no medicine for them,” the mother of 30-year-old detainee Tang Kai-yin said during the press conference. “I hope Hong Kong can help them to come back (then) at least we can see him. I don’t even know if he is dead or alive.”

In an interview with CNN following the press conference, the wife of 29-year-old detainee Wong Wai-yin said she had made repeated calls to the Shenzhen Yantian Detention Center, but had received no information about her husband.

“I want to tell my husband, don’t worry, I will wait for your return, whether it will take 10 years, 20 years or a lifetime,” she said. “We will not give up on you.”

In preparation for their ill-fated escape, a source familiar with the failed attempt said the fugitives had taught themselves to drive the speedboat, since no smugglers would risk the journey. The source did not want to be identified, for fear of prosecution.

The source said the goal of the fugitives was to reach the self-governing island of Taiwan, more than 700 kilometers (440 miles) away. Even on a calm summer day, the ocean swell off the east coast of Hong Kong bashes against the last, craggy uninhabited islands before the territory gives way to international waters.

Veteran mariners who spoke to CNN estimate a non-stop sea crossing in an open motorboat at high speed to Taiwan would take more than 14 hours, amounting to an exhausting, bumpy ordeal, with the risk of being caught out in one of the region’s frequent dangerous storms. Sailors would have to direct their craft using GPS and carry additional fuel, to avoid being stranded at sea.

While the boat carrying 12 passengers was intercepted, the source said two other boats carrying escapees successfully made the journey to Taiwan over the summer.

The Taiwanese government would neither confirm nor deny reports of boats carrying Hong Kong runaways reaching its shores.

“Our government has emphasized repeatedly that Taiwan supports Hong Kong’s democracy and freedoms, but it is also a society under the rule of law,” the island’s Mainland Affairs Council told CNN. “Based on safety considerations we absolutely do not encourage (them) to come to Taiwan using illegal means.”

Hong Kong’s government responded to an inquiry about the escapees with an appeal for the return of fugitives. “We urge other jurisdictions to take a clear position not to harbor any criminals who are involved in crimes in Hong Kong and to return them,” the city’s Security Bureau wrote in a statement to CNN.

Island sanctuary

Some Hong Kong activists are starting to see parallels between the current situation and the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, when hundreds of mainland Chinese protesters were smuggled by land and sea to Hong Kong via an organized pipeline called Operation Yellowbird. At the time, Hong Kong authorities did not return dissidents to mainland China.

“This time, the territory we need to escape from (includes) Hong Kong, and Taiwan becomes the destiny of people, the hope of Hong Kong people,” said Eddie Chu, a pro-democracy lawmaker.

Chu plans to resign his position in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, after the city’s government recently postponed elections by at least a year on public health grounds.

As authorities crack down on dissent in Hong Kong, a cottage industry of small businesses and organizations supporting the city’s protest movement is springing up in Taipei.

Aegis is a coffee shop decorated with giant murals depicting helmeted, goggled protesters as manga-style superheroes. Patrons are welcomed by a so-called Lennon Wall of Post-it notes with handwritten messages like “Stand with HK” and “Free HK,” a once-ubiquitous sight in Hong Kong at the height of last year’s protest movement.

The business employs activists who have fled Hong Kong.

According to the Taiwanese government, the number of Hong Kong residents settling in Taiwan more than doubled during the first six months of 2020, compared to the previous year.

One of the most famous recent emigres is Lam Wing-kee. For years, he ran Causeway Bay Books, a small store in the heart of Hong Kong specializing in sensational works critical of the Chinese leadership.

But in 2015, he and four of his colleagues disappeared from Hong Kong for months – only to reappear on Chinese state TV in a televised confession admitting to “illegal book trading.”

In a 2016 interview with CNN, Lam accused Chinese security forces of kidnapping him to the Chinese mainland and forcing the confession.

Three years later, Lam left Hong Kong for good, and started a new Causeway Bay Books in Taipei.

“Taiwan is a lot safer than Hong Kong,” Lam said. “I left a place where I may lose my freedom to a place where I have freedom.”

He spoke to CNN sitting beside the cash register in his shop, where he also sleeps at night to save rent. His desk is draped with a flag bearing the slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of our Time.”

The term has since been declared “subversive” by Hong Kong authorities, and those who use it could be prosecuted.

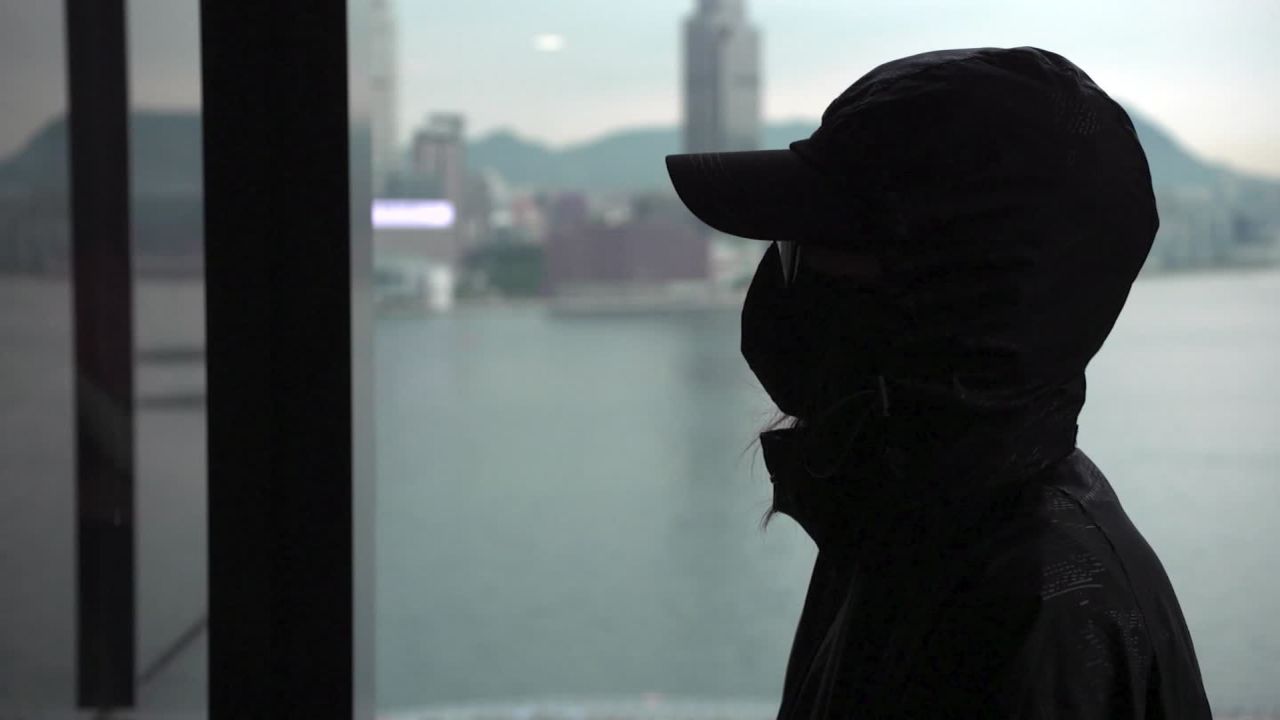

CNN has spoken to several frontline protesters who recently fled to Taipei to escape criminal charges in Hong Kong.

One 19-year-old man, who asked not to be identified, said he boarded a commercial flight to Taiwan in January, before the coronavirus pandemic triggered a lockdown.

“It’s hard for me,” said the teenage exile, adding he felt homesick and wanted to return. “I still want to (take part in) the political movement … (but) there’s no room for that in Hong Kong right now.”

Other exiles in Taiwan said they had heard of fellow activists trying to escape by sea.

“Right now everyone somehow is trapped in Hong Kong,” said an older activist, who flew to Taiwan in July 2019 after participating in the storming and vandalizing of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council.

“I can’t think of how we should keep fighting, or what young protesters should be doing now,” he added. “If we have a chance, we should escape.”

Advice from older generation

On a particularly humid September morning in Hong Kong, Ha Sze Yuen strolled along Aberdeen harbor, not breaking a sweat.

He pointed out a rubber dinghy on the back of a multi-million-dollar yacht, saying it was about the same size as the home-made boat he used to make the 1975 crossing from mainland China to Hong Kong.

Forty-five years later, Ha says he is dismayed at the Chinese government’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s autonomy.

“When I first came to Hong Kong I felt so free,” he said.

“I still believed in the Sino-British Joint declaration, which promised Hong Kong would remain unchanged for 50 years,” Ha added, referring to the agreement China made before the British handover of Hong Kong in 1997.

Ha said he supports those young Hong Kongers now risking their lives to flee into exile. And he feels regret that he did not move on from the city to another location out of the reach of communist China when he had the chance.

“I didn’t expect life would change so fast here,” he says.

CNN’s Sandi Sidhu, Eric Cheung, and Jadyn Sham contributed reporting.