Schools are reopening, amusement parks are welcoming back visitors, and outdoor dining is the new way to eat out. But despite the signs that life is returning back to normal, the coronavirus pandemic has gone nowhere.

That’s why a group of researchers at Duke University created a simple technique to analyze the effectiveness of various types of masks which have become a critical component in stopping the spread of the virus.

The quest began when a professor at Duke’s School of Medicine was assisting a local group buy masks in bulk to distribute to community members in need. The professor wanted to make sure the group purchased masks that were actually effective.

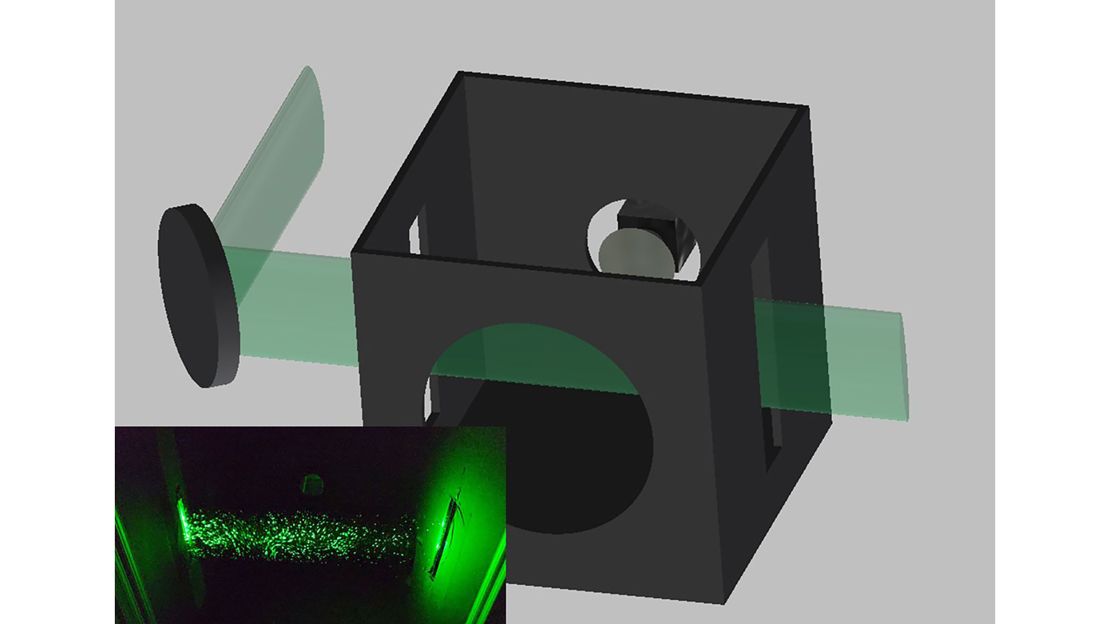

In the study published Friday, researchers with Duke’s physics department demonstrated the use of a simple method that uses a laser beam and cell phone to evaluate the efficiency of masks by studying the transmission of respiratory droplets during regular speech.

“We use a black box, a laser, and a camera,” Martin Fischer, one of the authors of the study, told CNN. “The laser beam is expanded vertically to form a thin sheet of light, which we shine through slits on the left and right of the box.”

In the front of the box is a hole where a speaker can talk into it. A cell phone camera is placed on the back of the box to record light that is scattered in all directions by the respiratory droplets that cut through the laser beam when they talk.

A simple computer algorithm then counts the droplets seen in the video.

Encouraging the use of effective masks

Public health experts have spent months emphasizing that masks are one of the most effective tools to help fight the pandemic, and many US states have now introduced some kind of mask requirement.

But when testing their effectiveness, researchers discovered that some masks are quite literally useless.

Researchers tested 14 commonly available masks including a professionally fitted N95 mask, usually reserved for health care workers. First the test was performed with a speaker talking without wearing a mask. Then they did it again while a speaker was wearing a mask. Each mask was tested 10 times.

The most effective mask was the fitted N95. Three-layer surgical masks and cotton masks, which many people have been making at home, also performed well.

Neck fleeces, also called gaiter masks and often used by runners, were the least effective. In fact, wearing a fleece mask resulted in a higher number of respiratory droplets because the material seemed to break down larger droplets into smaller particles that are more easily carried away with air.

Folded bandanas and knitted masks also performed poorly and did not offer much protection.

“We were extremely surprised to find that the number of particles measured with the fleece actually exceeded the number of particles measured without wearing any mask,” Fischer said. “We want to emphasize that we really encourage people to wear masks, but we want them to wear masks that actually work.”

While the setup of the test is quite simple – all that is required is a box, a laser for less than $200, one lens, and a cell phone camera – Fischer does not recommend people to set them up at home.

Unless a person is familiar with laser safety or has optic experience, mishandling powerful lasers can cause permanent eye damage. However, the researchers are hoping companies, museums and community outreach centers will set up the test to show people which masks are the most effective.

“This is a very powerful visual tool to raise awareness that a very simple masks, like these homemade cotton masks, do really well to stop the majority of these respiratory droplets,” Fischer said. “Companies and manufacturers can set this up and test their mask designs before producing them, which would also be very useful.”