Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus was watching late-night television when he saw a hospital boss criticizing him and Ethiopia’s Health Ministry, which he was leading at the time, for doing a terrible job. Instead of responding with a furious diatribe, as some political leaders might when watching their detractors on TV, he contacted the man, Dr. Kesete Admasu.

“Tedros called him in and said, well, if you have ideas and you’re critical get in here and help us fix it, and made him Deputy Minister, which gives you a sense of his leadership style in bringing in the smartest and the best and empowering them,” United States diplomat Mark Dybul, a professor at the Georgetown UniversityMedical Centerand co-director of the Center for Global Health Practice and Impact, told CNN.

“He took one of the worst ministries of health in the world, transformed it into one of the best, had to make very difficult political and health decisions and moves to make that happen,” Dybul said.

Today, Tedros – who is usually known by his first name, as is typical in Ethiopia – is again facingharsh criticism as he tries to balance powerful interests and reform a troubled institution facing a monumental challenge. Some believe that if anyone can change the World Health Organization and help the world deal with the coronavirus pandemic, it’s him.

“I think he’s doing an incredible job,” Peggy Clark, Executive Director of the Aspen Global Innovators Group who has worked closely with Tedros, told CNN. “I think that he is managing the situation as well as he can, even with the kind of ridiculous position that the US is taking at this time.”

US President Donald Trump has regularly attacked WHO during the pandemic, blaming it for multiple failures and alluding to China’s alleged influence at the organization as he moved to withdraw tens of millions in funding and, eventually, US membership.

Tedros has mostly reacted to these onslaughts with equanimity, but earlier this month condemned a “lack of leadership” in fighting the pandemic and made an emotional plea for global unity.

And when US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed the Director-General had been “bought” by China, Tedros pushed back harder, calling the comments “untrue and unacceptable.”

Tedros said that what “should matter to the entire international community is saving lives,” adding that WHO would not be distracted.

‘Rock star in the health world’

It is this single-minded determination that has characterized Tedros’s rise to global fame, with the WHO Director-General known for his passion and drive, say observers.

In a speech before he was voted in for a five-year term in May 2017, Tedros said that when he was seven, his younger brother died “from one of the many child killers in Africa,” Science Magazine reported. Tedros said that could easily have been him, and it was “pure luck” that he was now on stage running for a global leadership position. He said he was committed to reducing inequality and ensuring universal health coverage because he had grown up “knowing survival to adulthood cannot be taken for granted, and refusing to accept that people should die because they are poor.”

His path soon became clear. As a child living in Eritrea, then a region of Ethiopia, the WHO filtered into his consciousness, Tedros said in a speech last year. “I remember walking through the streets of Asmara with my mother as a small boy, and seeing posters about a disease called smallpox. I remember hearing about an organization called the World Health Organization that was ridding the world of this terrifying disease, one vaccination at a time.”

After gaining a biology degree from the University of Asmara in 1986, he began working for Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health and studied in Denmark, which opened his eyes to the value of universal healthcare. In 1992, he received a WHO scholarship for a Masters degree at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, before completing a PhD in community health at the University of Nottingham in 2000.

His thesis on malaria in the Tigray Region, where he grew up, was “outstanding” and “innovative,” his former supervisor wrote in a letter to The Lancet medical journal supporting his bid for the WHO job. “A lasting memory of that collaboration was Tedros’ innate ability to mobilize and inspire communities towards better health,” wrote Peter Byass.

Tedros became head of the Tigray Regional Health Bureau and spent a year as a minister of state before serving as health minister from 2005 to 2012. “There were really only a handful of ministers of health, globally, who were really doing exceptional work in the developing world, and one was Minister Tedros,” said Clark.

He found fame for “showing the way to a new era in world health,” in the words of former USAID Administrator Ariel Pablos-Mendez, particularly through his bold vision to hire 38,000 young, female community health workers in every village in the country to deliver basic family planning, child health and malaria care.

His work helped to reduce child mortality by two-thirds, HIV infections by 90%, malaria mortality by 75% and tuberculosis mortality by 64%, according to his WHO application.

“Tedros became kind of a superstar. He was a rock star in the health world, and everybody loved him, not only because he was really so charismatic and brilliant but also because as a man, he really was setting up for family and children and women; it was very unusual,” said Clark.

Clark believes Tedros’s health worker program made a profound difference to a poor country, and he announced similar priorities around universal healthcare, women and children and health emergencies on taking office at WHO

Many leaders in developing countries were dependent on wooing donors, said Clark,”but Tedros was so revered and beloved, he could literally walk into a room with donors and walk out with a multimillion-dollar check.”

Teshome Gebre, then the Carter Center’s Ethiopia representative for health programs, visited Tedros with his US bosses in 2006 to solicit help with tackling neglected tropical diseases. In a remarkable turnaround, Tedros instead persuaded them to donate $35 million to his malaria program, arguing that this was more urgent, life-saving work aimed at impoverished, marginalized people.

“They were extremely impressed with the way he really presented his arguments, his business case was so compelling,” Teshome told CNN.

“This is for me one of the most memorable experiences that I have ever had with Dr. Tedros. I think I can say in my lifetime, I have never seen this kind of completely unexpected outcome.”

The diplomat

Tedros’s ascension to leading WHO is groundbreaking on several fronts. He is not only its first African Director-General but also the first non-physician to lead the global health agency.

He has strong support from the continent, where South Africa in particular faces a battle to contain the virus.

On April 8, Tedros said he had been receiving death threats, abuse and racist comments, but brushed them off. “I’m proud of being black,” he said. “I don’t give a damn.”

He said when the whole black community or Africa was insulted “then I don’t tolerate it, then I say, people are crossing the line.”

His stint as Ethiopia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs between 2012 and 2016 saw him refine his diplomatic skills, persuading 193 countries to commit to financing the Sustainable Development Goals under the Addis Ababa Action Agenda.

He forged a friendship with former US president Bill Clinton through the Clinton HIV/AIDS Initiative, he has backing from tech tycoon Bill Gates, and he is on close terms with leaders including French President Emmanuel Macron and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa.

Stars including Lady Gaga, Jimmy Fallon and John Legend have also rallied around the WHO.

But some doubt Tedros precisely because of his diplomatic aptitude.

There were concerns when he was running for WHO leadership over his connection to an authoritarian government, one that Teshome concedes was “not very democratic.”

Georgetown University professor Lawrence Gostin, a supporter of Tedros’s WHO leadership rival David Nabarro, told CNN he was worried at the time because of Ethiopia’s “abysmal human rights record.”

Gostin – director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, now a WHO Collaborating Center – had reservations over alleged cover-ups of cholera outbreaks in Ethiopia, which Tedros denies.

Teshome agrees Tedros was “not transparent enough,” but observed that “if he does otherwise, he will be fired from his position.”

Gostin now speaks with Tedros regularly and calls him an “extraordinarily good” leader, and “one of the strongest director-generals in recent memory.”

Tedros inherited what The Lancet called a “bruised and apologetic” WHO after its poor response to the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa. The organization was bureaucratic, politicized, and underfunded and reform was desperately needed.

Tedros’s success in containing the Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was widely praised. “Unlike most director-generals, he leads from the front,” said Gostin. “He was on the ground, and probably, in harm’s way.”

WHO spokeswoman Margaret Harris was in the DRC at the time, and recalls Tedros genuinely participating on those visits, talking to local people and taking selfies with anyone who asked. When a public health emergency was declared, Tedros called in from the DRC, said Gostin.

“I give him a lot of credit for putting everything on the line. He’s a very passionate man, he cares a lot and I think it shows. You can absolutely feel the sting of his wrath, and I have, but you can also hear the compassion.”

Gostin recalls accidentally sending Tedros a text meant for his wife, saying he missed her. “‘I love you too Larry, it’s always good to hear from you,” Tedros joked in reply.

The US-China issue

Many describe Tedros as humble. Teshome says Tedros is “not an authoritarian kind of guy,” calling him “humorous, down to earth, very respectful to people.”

But the Trump administration is not alone in its concerns about how Tedros deals with autocratic leaders.

In October 2017, Tedros picked Zimbabwe’s then-president Robert Mugabe as a WHO goodwill ambassador – quickly reversing the decision following an outcry.

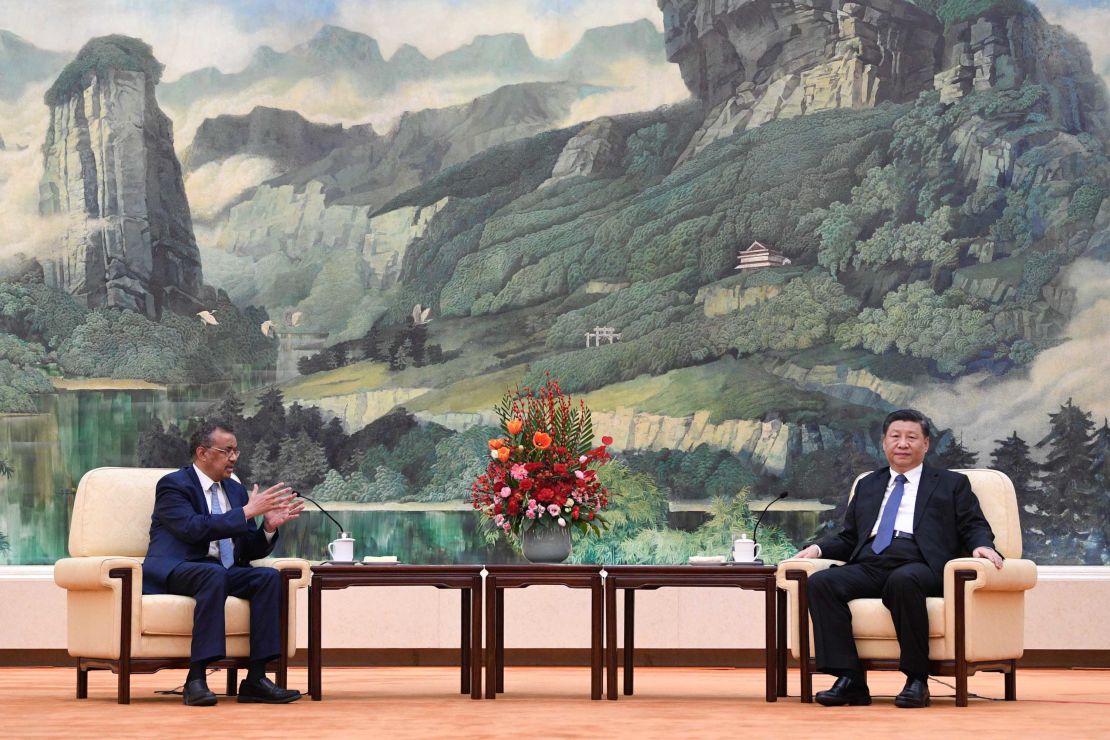

Critics have questioned whether WHO is independent enough, pointing to Tedros’s effusive praise of China’s pandemic response and recirculation of China’s statements that there was “no clear evidence” of human-to-human transmission of the coronavirus on January 14.

Gostin doesn’t believe WHO knew China was being misleading, but says it could have responded better.

“I would have said, this is what the Chinese government is informing us about this outbreak and we have no way of independently verifying it,” said Gostin.

Tedros, he added, believes that “it’s better to use quiet diplomacy behind the scenes rather than criticize the government publicly.”

Tedros has not been as full of praise for the effective pandemic response of Taiwan, a territory that China has successfully blocked from WHO membership, said Gostin. “Politics are at play. There’s no doubt about it,” he said.

But he acknowledges that Tedros did avoid antagonizing the Chinese government.

“He probably does read strongmen leaders like [Chinese President] Xi Jinping well, because if he publicly criticized China, it might have pushed China to be less cooperative and less transparent, and defensive. And he was trying to coax them from inside. And more than coax, he was actually quite firm with the Chinese government early on behind closed doors – but it was at a cost to the reputation of the WHO.”

The agency’s image also suffered when it did not advise against travel to China. Tedros said at the time: “Such restrictions can have the effect of increasing fear and stigma, with little public health benefit.”

WHO the world deserves

The truth is that WHO’s power is limited. Unlike other epidemics, coronavirus has ravaged wealthy and poor countries alike, and leaders started taking independent action early in closing borders or enforcing measures without recourse to WHO.

“The world has the WHO it deserves. And the reason I say that is because it funds the WHO pitifully, about the size of one large US hospital; WHO has no control over two thirds of its budget, and no organization can succeed that way … when anything goes wrong, they don’t get political backing, they get blamed,” said Gostin.

WHO’s public messaging has at times felt confused. Concerned about low-income countries and a lack of personal protective equipment, it didn’t recommend universal mask use early on. WHO delayed in declaring coronavirus a public health emergency even though there is no international standard for what a pandemic is. “It hurt them politically,” Gostin said. “But it did not change the trajectory of the pandemic one iota.”

However, despite the devastation of the virus and serious charges laid against WHO, Tedros has become a household name and a leading figure on the world stage.

The 55-year-old father of five is now a familiar face at regular news conferences, doling out warnings and vital guidance for the world. His at times emotional statements that there will be “no return to the old normal” and that this is the “worst global health emergency ever” are likely to appear in history books.

Dybul says Tedros has rapidly reoriented WHO from its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, by placing staff in countries where health problems are, much as he did in Ethiopia, making the WHO able to respond rapidly to Ebola and the coronavirus. “He learns extremely well, and very quickly. He’s incredibly smart, and he adapts,” said Dybul.

He said claims WHO should have spoken sooner on asymptomatic cases, for example, were unfounded as there was only limited evidence. “They do rapidly sift through data; he’s keeping in a very technically sound strong leadership role, which is not easy to do during the middle of a global crisis,” said Dybul.

“He was able to mobilize the availability of test kits, so that countries could have them available rapidly. He put together the network for vaccines, that is a global network for vaccine trials, which only WHO can do … they’re providing daily important technical support to countries so that they can put in place the test trace and quarantine approaches.”

Had the US accepted the test kits from WHO, Dybul believes it could be in a very different position.

The dispute between the US and China is of course complex, but Tedros is trying to get on with the job as the future of the world hangs in the balance. The future of WHO is also at stake. How the agency fares in helping to distribute vaccines, a mission that first piqued Tedros’s interest in childhood, will be crucial. It is a challenge that demands much of an organization with little real power.

The US election could decide whether the WHO will lose its biggest donor, or becomes stronger and empowered thanks to funding and political support from a change of government.

At the center of the chaos is a man whose life has been leading to this moment: Tedros.