Teeth, bones, ornaments and stone tools from the Bacho Kiro cave in current-day Bulgaria have revealed that the first modern humans were settled in Europe as early as 47,000 years ago, according to new research.

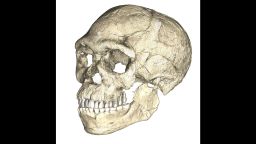

Pendants made from animal teeth and stone tools were previously attributed to Neanderthals. But precise dating techniques revealed that bone fragments and teeth actually belonged to early modern humans. Researchers believed that modern humans arrived in Europe around 45,000 years ago and knew from the fossil record that the last of the Neanderthals went extinct in western Europe 39,000 years ago.

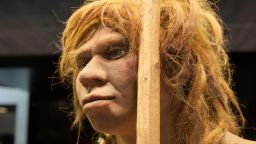

The new findings pushed back the arrival date of modern humans in Europe and allowed for even more overlap of modern humans and Neanderthals, also called Neandertals, raising intriguing questions about what this overlap caused and created.

“Pioneer groups of modern humans entered the mid-latitudes of Eurasia for the first time” 47,000 years ago, said Jean-Jacques Hublin, study author and director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology’s department of human evolution, in an email to CNN. “They brought new behaviors into Europe and interacted with local Neandertals. They exchanged genes but also techniques: The kind of pendants found in Bacho Kiro will be later also produced by the last Neandertals in Western Europe.”

“This early wave of modern peopling largely predates the final extinction of the Neandertals in western Europe 8,000 years later,” Hublin said. “Such a chronological overlap of the two species in Europe indicates that the replacement of one species by the other was a more complex process than what has been so far envisioned by most scholars.”

Two studies about the Bacho Kiro cave findings were published Monday in the journals Nature and Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Researchers excavated the cave in 2015, investigating a layer that was rich with thousands of animal bones, tools made from stone and bones, pendants and beads and the fragmented remains from five Homo sapiens.

While the organic matter of the bones were well preserved, which meant that they could be accurately dated, the bones themselves were fragmented. Analytical techniques such as molecular analysis and protein sequences allowed them to identify if the bones belonged to animals or humans. But the animal bones are just as important because they show evidence of the impact of ancient humans.

“The majority of animal bones we dated from this distinctive, dark layer have signs of human impacts on the bone surfaces, such as butchery marks, which, along with the direct dates of human bones, provides us with a really clear chronological picture of when Homo sapiens first occupied this cave, in the interval from 45,820 to 43,650 years ago, and potentially as early as 46,940 years ago,” said Helen Fewlass, study author and doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in a statement.

The researchers were able to obtain incredible precision in their dating of the bones, something that’s unusual for this particular time period based on the fragmented evidence left behind. Their unique combination of different analyses, including radiocarbon and genetic dating, is something that the researchers believed would soon become standard in studying sites from this time period to determine how modern humans replaced Neanderthals, Hublin said.

The modern humans who arrived in Europe 47,000 years ago likely came from Africa, or “regions at the gate of Africa,” Hublin said. And the stone tools they left behind at the cave are similar to those found at similarly dated sites in Turkey, Lebanon and Israel, she added.

The stone tools included flint, some of which was brought to the cave from 111 miles away, and shaped into pointed blades for hunting and butchering animals. The most popular animals hunted by these modern humans included bison and red deer. Then, their bones were made into other tools or personal ornaments. Some of the pendants they wore also included teeth from cave bears.

The cave serves as an important site of the Upper Paleolithic period, which began between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago.

“The Initial Upper Paleolithic in Bacho Kiro cave is the earliest known Upper Palaeolithic in Europe,” said Tsenka Tsanova, study coauthor and postdoctoral student in the department of human evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in a statement. “It represents a new way of making stone tools and new sets of behavior including manufacturing personal ornaments that are a departure from what we know of Neanderthals up to this time.

“The Initial Upper Paleolithic probably has its origin in southwest Asia and soon after can be found from Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria to sites in Mongolia as Homo sapiens rapidly dispersed across Eurasia and encountered, influenced and eventually replaced existing archaic populations of Neanderthals and Denisovans,” Tsanova said.

And the blade-like tools and pendants represent some of the earliest displays of modern technology at the time, which was used and shared by modern humans as early as 47,000 years ago.

“If Neanderthals had created these ‘modern’ tools and jewelry, it would have indicated they had more advanced cognitive abilities than previously recognized,” said Shara Bailey, study coauthor and an associate professor in New York University’s department of anthropology. “Nonetheless, there are some similarities in manufacturing techniques used by Homo sapiens at Bacho Kiro and Neanderthals elsewhere, which makes clear that there was cultural transmission going on between the two groups.”

Now, the researchers are left to ponder more questions based on their findings, such as what happened during the 8,000 years that Neanderthals and modern humans overlapped, before Neanderthals disappeared for good.