The level of microplastics on the seafloor is at its highest ever level, with up to 1.9 million pieces covering just one square meter.

Researchers said they were “shocked” by the volume of microplastics found on the seafloor bed.

The accumulation of floating plastic accounts for less than 1% of the 10 million tons of plastic that enter the world’s oceans each year, according to research spearheaded by the University of Manchester in the UK.

The missing 99% is thought to accumulate in the deep ocean, but until now it has not been clear just where it has ended up.

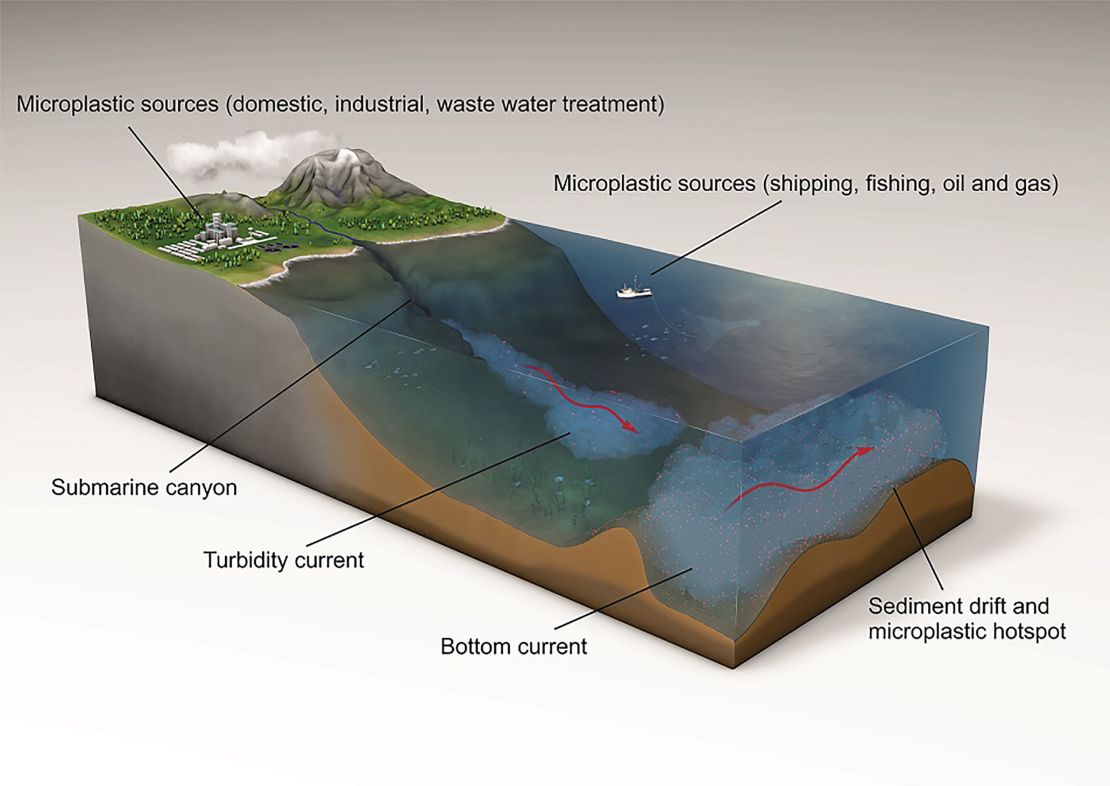

A study published Thursday in the journal Science reveals that deep sea currents act as conveyor belts, transporting tiny plastic fragments and fibers across the seafloor.

Thanks to these currents, microplastics gather within huge sediment accumulations, which the researchers from the UK, Germany and France dubbed “microplastic hotspots.”

Dr. Ian Kane, from the University of Manchester and the lead author, said the team was “shocked” by the discovery.

He told CNN the “garbage patches” of bottles, bags and straws often seen floating on the surface of the water is “the tip of iceberg.”

“We were really shocked by the volume of microplastics we found deposited on the deep seafloor bed,” he said. “It was much higher than anything we have seen before.”

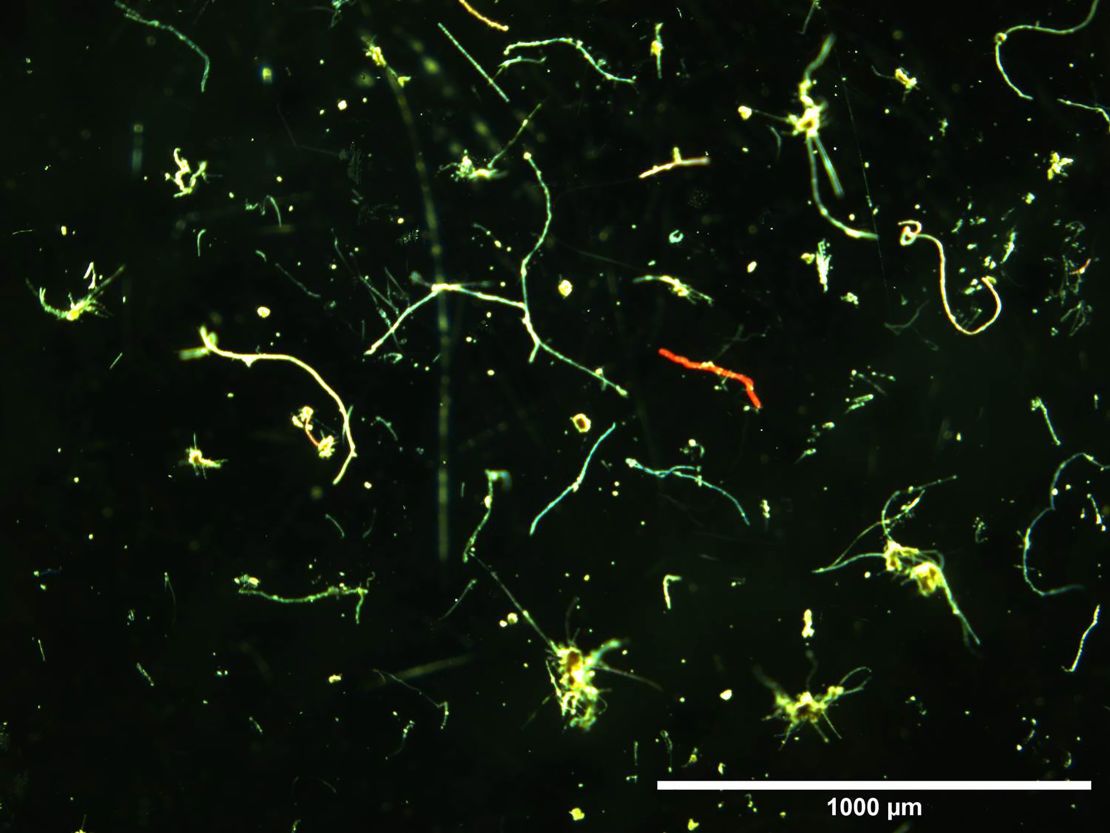

These microplastics are mainly comprised of fibers from textiles and clothing not filtered out in waste water treatment plants.

Being so tiny means they are not easily captured by the conventional water treatment system and so are easily flushed through to rivers and the sea.

Samples of sediment were collected by the Tyrrhenian Sea, part of the Mediterranean located off the west coast of Italy.

Scientists separated the microplastics from the sediment and determined how ocean currents controlled the distribution of microplastics on the seafloor.

Once they drift into the ocean, the microplastics are rapidly transported by episodic turbidity currents, which are effectively powerful underwater avalanches. These carry the microplastics down underwater canyons to the deep seafloor.

“By themselves the microplastics are relatively inert, but through time they act as a nucleus for contaminants and toxins,” said Kane.

Microplastics can be ingested by micro-organisms and pass up the food chain.

The study, the authors say, shows the first direct link between the concentrations of the seafloor microplastics and currents, which scientists hope will allow them to predict hotspots and research the impact on marine life.

Chris Thorne, oceans campaigner at Greenpeace UK, called for a rethink of “throwaway plastic.”

“Microplastics can be ingested by many forms of marine life,” he said, “and the chemical contaminants they carry may even end up being passed along the food chain all the way to our plates.”