For 18-year-old Huang Yiyang, school starts when she opens up her laptop.

Over the past two weeks, there have been no school bells, bustling corridors, busy canteens or uniforms. Instead of physically traveling to her public school in Shanghai, Huang sits at her laptop from 8 a.m. until 5 p.m. often in her pajamas, watching livestreamed class after livestreamed class.

For physical education class, her teacher performs exercises for students to follow. For English, she sits silently through lectures to virtual classrooms of 20 to 30 students.

She puts stickers or tissues over her webcam, soher classmates can’t see her if a teacher calls on her to answer a question. “We’re at home, so we don’t look so good,” she says.

Huang barely leaves the house, and she hasn’t seen her friends for a month. But while she is isolated, she’s also part of what may be the world’s largest remote learning experiment.

China is battling a deadly coronavirus outbreak that has killed more than 2,700 in the country alone. In a bid to stop the spread of the disease, schools across the country are closed, leaving about 180 million school-aged children in China stuck at home.

And mainland China is just the start. Millions of students in Hong Kong, Macao, Vietnam, Mongolia, Japan, Iran, Pakistan, Iraq and Italy have been affected by school closures. For some, that means missing class altogether, while others are trialing online learning. Authorities in the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom have indicated that, if the outbreak gets worse, they could shut schools, too.

But while online learning is allowing children to keep up their education in the time of the coronavirus, it’s also come with a raft of other problems. For some students, the issues are minor – shaky internet connections or trouble staying motivated. For others, the remote learning experiment could come at a cost of their mental health – or even their academic future.

What it’s like doing school from home

The components are the same: a laptop, an internet connection, and a bit of focus. But thetype of online study differs from school to school, and country to country.

For Huang, learning at home means spending hours in front of a computer with little social interaction. There’s no discussion in class, and she often can’t hear her teacher because of the poor internet connection. She feels her classmates – and their teachers – are struggling to stay motivated.

“We cannot give (the teachers) a response even though they want it. So they feel bad and we feel awkward as well,” she said.

Even after class, her work isn’t over. She usually stays up until about 10 p.m. each night, completing homework which she submits online. Although she doesn’t see her friends face-to-face, Huang says she actually feels closer to them – they talk more than they would usually on Chinese online messenger apps such as WeChat and QQ because they’re all hungry for contact.

“Because we can’t meet anyone our age in reality, so we have to go online.”

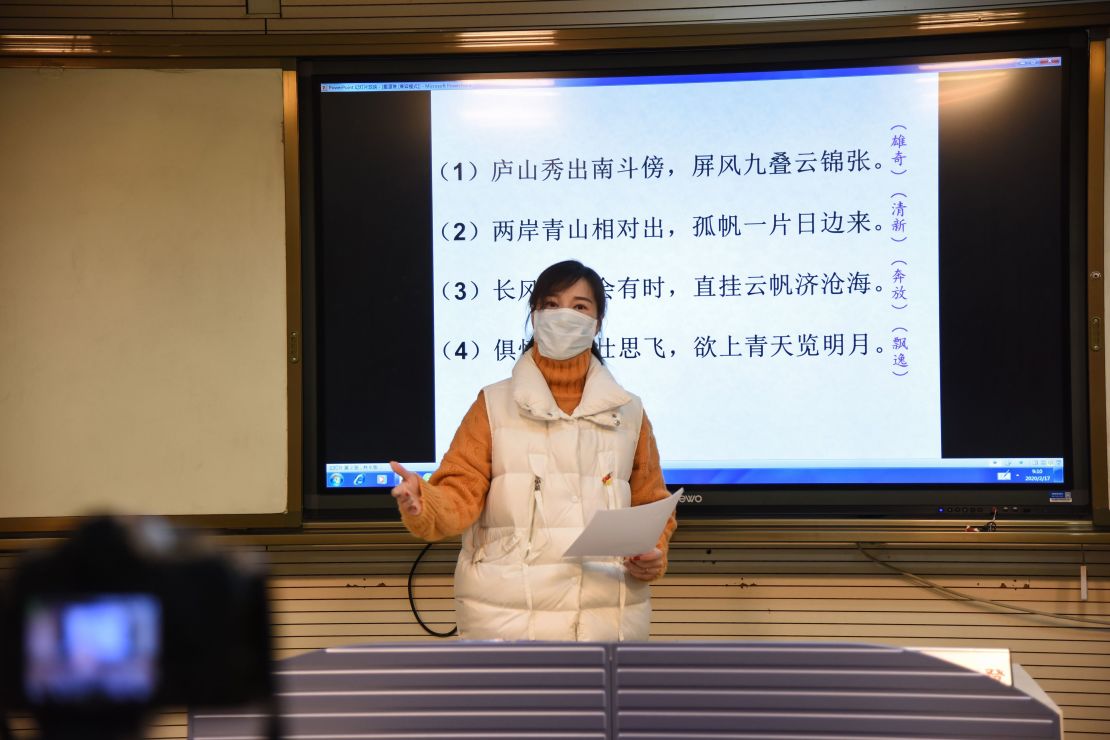

Across China, primary and middle school students are required to provide online learning, according to state media agency Xinhua. China has started broadcasting primary school classes on public television, and launched a cloud learning platform based on its national curriculum that 50 million students can use simultaneously.

In Hong Kong, where schools have been closed for a month, some teachers are doing things differently.

At the International Montessori School, students work together in small groups on Google Hangouts so they can all see and talk to each other.

The school started off just posting videos and activities for students on their website, but quickly realized that it was crucial for children to see each other and speak with their teachers. Now they study together in small online groups.

“They were all getting cabin fever – they were all locked inside in apartments,” said principal Adam Broomfield. “I’ve never experienced a school closure like this.”

The different learning style has actually led to innovation, he said – a student made a video explaining how they solved a math problem, and a teacher made a video from a beach to help with a geology lesson.

Schooling in Italy

Students in Hong Kong and mainland China have been isolated for weeks already, but in Italy, where the number of people infected with coronavirus soared past 800 this week, remote learning has just started.

What to know about the coronavirus

Schools closed this week in the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto, which include the cities of Milan and Venice, and together have a combined population of about 15 million.

In Milan, Gini Dupasquier’s two daughters have been learning through a combination of live PowerPoint presentations, group work with other students over Google Hangout, and a live chat with teachers.

“Emotionally, they’re fine,” Dupasquier said. “They’re having fun with this new method. So far I see no problem at all.”

A bigger problem for her – like other working parents – is having to balance being at home with her child with the demands of her job as a consultant. “I need to adapt my working hours,” she said. “The balance is a bit tough.”

In Casalpusterlengo, a northern Italian town in the so-called “red zone” where tens of thousands of residents have effectively been cut off from the rest of the country, Monica Moretti’s 15-year-old daughter doesn’t have access to livestreaming – instead, she’s doing homework using an electronic notebook. Unlike many children in mainland China, every afternoon she goes for a walk.

Future-defining exams

Students in senior grades are potentially facing bigger problems than falling behind on their schoolwork.

Jonathan Ye, an 18-year-old high school student in his final year at international school Shanghai Pinghe, has conditional entry to university in the United Kingdom. He still needs to do well on his final International Baccalaureate exam in May if he wants to start university overseas – something he’s been working toward for years.

“If I do not do well on that exam, then I’m screwed,” he said. “I think I’ll be OK because I like to self-study, but I’m not sure. I still get nervous because we are not going to school right now, so we might be missing information from the teacher.”

But Ye’s situation is better than most.

In June, the vast majority of final year students in mainland China are due to sit the gaokao – the notoriously intense and ultra competitive university entrance exams. Even at the best of times, those exams can change lives – they can be the difference between a prestigious university and no university at all.

Students become consumed by studying for the test, and teachers sometimes tell them to focus on nothing else. While it’s possible to resit the gaokao, that would require studying your whole final year again.

The Ministry of Education said it will assess and decide whether to delay the gaokao. Beijing authorities have already said there will be an online mock exam ahead of the gaokao – although that isn’t the actual gaokao exam.

Although Hong Kong schools are shut until April 20, the city will still hold its university entrance exam on March 27 as planned. The only difference: students will be required to wear face masks and desks will be moved further apart than normal.

That’s also an issue for students sitting other exams. Hong Kong-based Ruth Benny found home study just wasn’t working for her 14-year-old daughter, who is sitting GCSEs this year. “There was no learning happening. It was just like a big long holiday,” she said. Her daughter has now transferred to boarding school in the United Kingdom.

Some parents have raised concerns over paying expensive international school fees when their child isn’t doing regular schooling.

Benny, who runs education consultancy Top Schools, said that if schools are doing the best they can, there’s no need for reimbursement.Her 12-year-old son normally boards during the week at Harrow International School in Hong Kong, but they’ve reimbursed the cost of boarding while her child is out of school. “It’s really as good as it can be, but I know that it’s not like that for all schools.”

Broomfield, the principal of International Montessori School, said that if schoolsreimbursed parents, the schools might not survive.

“We still have to run, we still have to pay our staff. We still want a school here when all this is over,” he said. “I just don’t see how those refunds can be provided.”

And he pointed out that it had been a difficult time for teachers too, with much longer hours than usual, and a steep learning curve, particularly for the “tech dinosaurs” on their staff.

In a way, the situation was like trying to plumb a bathroom with the water still running, he said. “We had very little preparation for this,” he said. “If you’re going to renovate your bathroom, you turn your water off first. This was a whole replumbing of education, but we had to do it on the run.”

Psychological effects

There’s also a risk that studying from home could impact children psychologically.

Hong Kong-based mental health expert Odile Thiang said the loss of routine and the loss of social activity could have a big impact on children, who were also stuck inside with their parents during an already stressful time. “There’s also that general fear of contamination that people are feeling, so everything is adding up.”

“(The psychological lessons) is yet to be learned, to really see what is going to come out of this major public health experiment that we’re doing here,” she said, adding that children tend to be very resilient.

Chris Dede, a professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education, said there were plenty of studies showing the negative psychological effects on students who had been isolated from their peers after suffering serious illnesses.

Children studying from home could experience the same effects. But he pointed out that, in this situation, whole schools were studying remotely – not just one single student who might feel lonely and left out.

“The shared problem becomes a way of having shared support,” he said.

Is studying remotely a good thing?

It’s not the first time that schools have had to shut down or experiment with remote learning. In countries with particularly harsh winters, children sometimes find their school canceled for “snow days.” In Hong Kong, some schools canceled classes last year over the ongoing pro-democracy protests.

And it’s not like education experts have never thought of studying without a face-to-face teacher before. Children in remote parts of Australia have long taken lessons via education programs over the radio. And, in China artificial intelligence has been touted as a way to ensure students in rural communities get a better education.

According to Dede, a mix of online and face-to-face teaching is better than learning entirely offline, or entirely online. But the crucial thing isn’t the medium, he said – it is the quality and the method of teaching.

“The worst thing for children would be just to be isolated, at home, without emotional support from their friends, without the opportunity to have a skilled educator to help them learn,” he said.

He sees this as a chance for educators to experiment with new teaching approaches, and then take what works back into the physical classroom.

Regardless of the teaching style, students were still lucky in a sense that this was happening now.

“We have social media, and the internet, and we have smart phones. So the degree of isolation and the degree of lost opportunity to learn would have been much greater if this happened two decades ago,” he said.

CNN’s Jo Shelley reported from Milan, Italy. CNN’s Yong Xiong contributed reporting from Shanghai. CNN”s Kristie LuStout, Jadyn Sham, and Eric Cheung contributed from Hong Kong.