Protesters in Hong Kong will hold a celebratory, pro-US rally Thursday after President Donald Trump gave them what one prominent activist termed a “timely Thanksgiving present.”

Trump signed an act in support of the protest movement despite a potential backlash from Beijing that could derail delicate US-China trade talks, after it was passed almost unanimously by both houses of Congress.

Anti-government protesters in the semi-autonomous Chinese city have long campaigned in favor of the bill – which would permit Washington to impose sanctions or even suspend Hong Kong’s special trading status over rights violations. Trump’s decision to sign the act gives the movement a second major symbolic victory in a matter of days.

On Sunday, pro-democracy candidates scored a landslide victory in district council elections, framed as a de-facto referendum on the protest movement, which began in June in opposition to a controversial extradition bill but has grown to include demands for greater democratic freedoms and inquiries into alleged police brutality.

Activists and pro-democracy politicians in the city celebrated online after Trump signed the bill, with former lawmaker Nathan Law calling it a “timely Thanksgiving present.”

Shortly after the bill was signed into law, China’s Foreign Ministry accused the US of “bullying behavior,” “disregarding the facts” and “publicly supporting violent criminals.”

“We urge the United States not to insist on going down this path, or China would firmly strike back and the United States would have to bear all consequences,” the statement read.

The Chinese government also summoned the US envoy to China, Ambassador Terry Branstad, to “lodge solemn representation and strong protest” over the measure.

There are concerns that Beijing and Washington’s disagreement over Hong Kong could affect trade negotiations between China and the US, as the two sides previously appeared to be nearing the initial stages of a deal. Asian markets dropped slightly after Trump signed the bill, a sign that investors may be worried about how the law could affect talks.

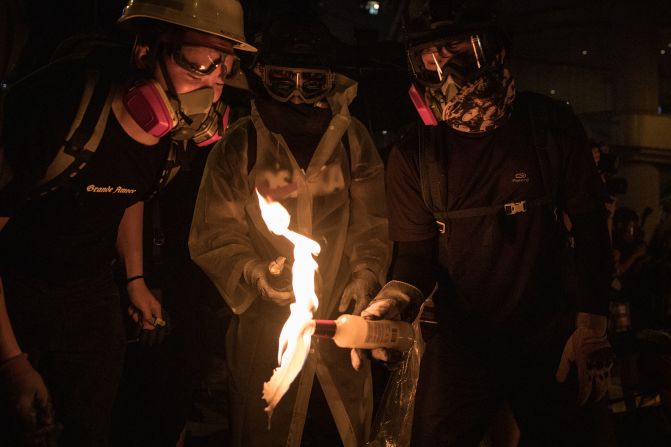

While the unrest in Hong Kong began with peaceful mass marches, as the movement has dragged on, protests have gotten increasingly violent, and the last two weeks saw several universities occupied by demonstrators.

The most intense standoff – between police and protesters around the centrally located campus of Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) – appears to be coming to an end.

A government “safety team” entered the campus Thursday to begin cleaning up, likely to be a painstaking process because of the hundreds of unused petrol bombs scattered around the school’s grounds.

What happens next?

Though the Hong Kong legislation was passed with overwhelming bipartisan support in Washington, it’s unlikely to have any immediate, tangible effect.

The main bill that Trump signed into law, the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, requires the State Department to annually review whether the city is “sufficiently autonomous” to justify its special trading status with the US.

If it is found not to be, the law could result in Washington withdrawing that status, which would be a massive blow to Hong Kong’s economy.

The bill also lays out a process for the President to impose sanctions and travel restrictions on those who are found to be knowingly responsible for arbitrary detention, torture and forced confession of any individual in Hong Kong, or other violations of internationally recognized human rights in the Asian financial hub.

There is no indication however that Trump intends to enact any of the powers in the act anytime soon, and in a statement, the White House said it would only enforce parts of the law because “certain provisions of the Act would interfere with the exercise of the President’s constitutional authority to state the foreign policy of the United States.”

There is also concern that any change to the US-Hong Kong trade relationship could disproportionately affect average Hong Kongers, rather than Beijing or the city’s leaders.

The US is Hong Kong’s second biggest partner in terms of total trade, according to figures from the Hong Kong government. Washington exported $50 billion worth of goods and services to the territory in 2018, US figures show.

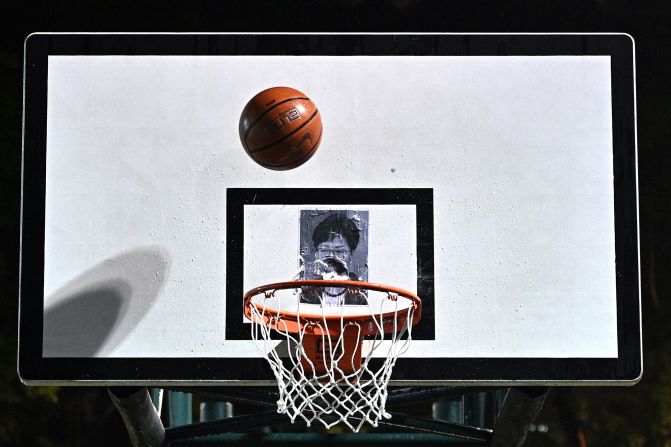

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

Susan Thornton, who served as the State Department’s top Asia diplomat early in the Trump administration, said in an interview last month that she worried the legislation could end up “punishing exactly the wrong people.”

A companion piece of legislation passed by Trump bans the export of certain crowd control items to Hong Kong, like tear gas and rubber bullets – gear that the city could also buy from mainland China.

Hong Kong police have fired around 10,000 rounds of tear gas and about 4,800 rubber bullets during the months of unrest, the city’s security minister John Lee said Wednesday. He added that more than 5,800 people have been arrested since June in relation to the protests.

In a statement after Trump signed the bills into law, the Hong Kong government said they were “unreasonable” and would “send an erroneous signal to protesters, which is not conducive to alleviating the situation in Hong Kong.”

Both Beijing and Hong Kong accused Washington of intervening in the city’s and China’s internal affairs.

Sen. Marco Rubio, who authored the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, has previously denied that charge.

“Our treatment of Hong Kong is an internal matter. It’s a matter of our own public policy,” Rubio said in an interview with CNBC. “We have a right to change our law.”