In the middle of a beautiful sunset in May, Emily’s boyfriend knelt before her on a beach in Japan and proposed. Overjoyed, she said yes.

They envisioned starting a family together in their home of Hong Kong. But within a month, their plans – their whole vision of a future together – had been thrown into chaos.

Four months into the largest protests in the city’s history, Emily is looking for a way out of the embattled city.

Now, along with her fiancé, Emily – who declined to give her full name due to political sensitivities – is actively looking to emigrate to another country within the next two years, including the UK and the US.

“I will have children one day,” the 25-year-old office worker told CNN. “I don’t want them to live in a police state where they cannot freely express their opinions.”

Time to leave

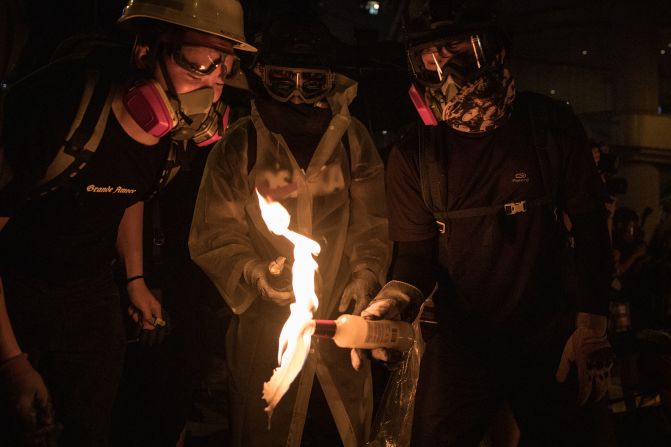

The semi-autonomous Chinese city is in its 18th consecutive week of anti-government protests. The unrest has grown increasingly violent on both sides, with protesters using petrol bombs and setting fires, and police firing tear gas and water cannons. During citywide protests on October 1, police used lethal force for the first time, after protesters attacked several officers.

Hong Kong has a history of politically driven waves of emigration. The first occurred in 1984, when the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed after years of secret negotiations, setting the stage for the city’s handover from British to Chinese control in 1997. The second started in mid-1989, after the massacre of pro-democracy protesters in Beijing led many to doubt China’s commitments to preserving Hong Kong’s freedoms. While many Hong Kongers who emigrated before 1997 returned to the city when Chinese rule was established and the “one country, two systems” formula – by which Hong Kong retained its own economic and legal systems and a degree of autonomy – seemed to be working, a substantial number retained foreign passports, giving them the option to leave in future.

Originally sparked by a now-shelved extradition bill with China, the protests have demonstrated just how the trust and hope regained after the Tiananmen Square massacre has been eroded in recent years, with many – especially younger Hong Kongers – looking forward with great trepidation to 2047, when current constitutional arrangements run out and Hong Kong could become fully a part of China, governed just like any other city.

Some Hong Kongers have expressed this distrust – and their frustration with Beijing’s increasing encroachment on the city’s freedoms – by taking to the streets, but others are looking for a way out.

According to a survey by the University of Hong Kong in June, nearly half of the city’s population was willing to consider emigration if the extradition bill – which critics feared could leave any Hong Konger open to prosecution in China – passed. While the bill was suspended following mass protests (and the government has since announced its full withdrawal), the unrest has continued to shake people’s willingness to stay. Research by YouGov in July found similar numbers wanting to leave. Of those surveyed, two out of three who were eager to leave were between the ages of 18 and 34. Half of those wanting to leave held university degrees.

The city’s young professionals don’t just want to move, they want to move soon. YouGov’s survey found that a quarter of those who want to migrate are likely to do so within the next three years. Government data provided to CNN shows that the number of applications for a certificate that is necessary for Hong Kongers applying for visas overseas surged over 50% from May to August this year.

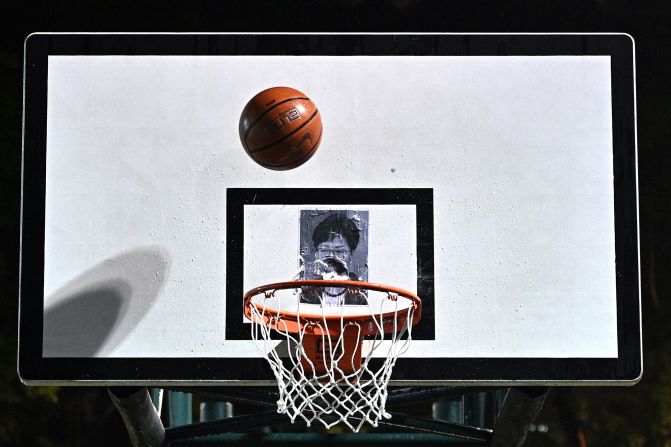

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

Looking for a way out

According to Athena Law, head of immigration at L&K Holdings migration agency, the number of inquiries has increased 200% since June, with many made by people in their 20s.

“(This) increase is related to what’s happening in society,” Law told CNN. “Many of our clients expressed concern over the social unrest.”

Another migration agent, John Hu, said inquiries had snowballed 300% since June – and it was not only young people who wanted to leave. People in their 30s and young families were also interested in a fresh start overseas, Hu added.

Last month, the city’s leader Carrie Lam began a series of dialogues with Hong Kongers, promising to listen to their concerns and work towards a solution to the monthslong unrest.

“Hong Kong has faced – and overcome – momentous challenges every decade since the end of World War II,” Lam wrote recently. “This should tell us something about the people of Hong Kong: They are resilient and resourceful. It should also tell us something about the values that the Hong Kong people share and our common aspiration for a bright future.”

Timon, who also declined to give his full name, is just the type of Hong Konger Lam is seeking to reassure.

The 32-year-old accountant never thought about leaving the city before the unrest started in June. He attended several large-scale demonstrations, but is increasingly dubious that any longterm change can happen in Hong Kong.

“Before the protests, I was focused on pursuing my career and my wife was ready to work as a nurse,” he said. “(But now) we want to move to Australia, as we see that the totalitarian government is unlikely to change.”

Now, Timon said he is willing to scrap nearly a decade of accounting experience to get retrained as an electrical engineer – a career with more prospect for migration. He said his main concern was his 18-month-old son’s education.

“I want my child to have critical thinking, but the education here is going to worsen in this political atmosphere, with the white terror created by the police and the government,” Timon said. “I don’t want my child to grow up here.”

Island sanctuary

Government data shows that between 1997 and 2018, Australia, Canada and the US were the three most popular destinations for emigrating Hong Kongers. In recent months, however, Taiwan has surged to become the top choice, according to YouGov.

The self-ruled island has long been popular with Hong Kong tourists, but its open support for the city’s pro-democracy movement and apparent commitment to liberal values has made it an increasingly attractive destination to move to. In September, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen said that “when necessary and based on humanitarian concerns, we will provide necessary assistance to Hong Kong residents in Taiwan, and will not just stand on the sidelines and watch.”

According to Taiwanese immigration data, the number of approved applications for residence from Hong Kongers rose almost 50% between May and August. An immigration department spokeswoman confirmed this was in line with a surge in applications in general, but was not able to provide a detailed breakdown.

Ken Lui and his wife understand the island’s appeal – Taiwan is close to Hong Kong geographically, culturally and linguistically, and he said he hopes to open a boutique or restaurant on the island after moving.

The 36-year-old fashion shop owner said his business was affected by the city’s protests, and he didn’t see a way out except by leaving.

“They (the government) keep suppressing our freedom of speech,” he said. “I don’t think there will be any big changes in Hong Kong. I hope that Hong Kong will be fine, but does the government listen to its people?”

Lui said he was concerned about leaving his family behind, a fear Emily shared. But both said they felt they were making the right decision. Emily even hopes to bring her family and friends with her to a new country.

“There’s a Chinese saying that we have to first take care of ourselves, then we take care of the family. And at the end, we take care of our society, our country,” Emily said. “I can live with my family (anywhere) in the world. If there’s family, there’s home.”