“The Paracel Islands!” the teacher shouts.

“Belong to Vietnam!” call back about 30 schoolchildren, even louder. Their chant echoes through the three-story Paracel IslandsMuseum in Da Nang, which officials say cost the Vietnamese government $1.8 million to build.

Since opening in 2018, about half of its 40,000 visitors have been schoolchildren, who can explore exhibits, including documents, maps and photographs, all curated to hammer home one point.

The Paracel Islands belong to Vietnam. Not to China.

Named by 16th century Portuguese mapmakers, the Paracels are a collection of 130 small coral islands and reefs in the northwestern part of the South China Sea. They support abundant marine life. But more than being just a rich fishing ground, there is speculation the islands could harbor potential energy reserves.

They have no indigenous population to speak of, only Chinese military garrisons amounting to 1,400 people, according to the CIA Factbook.

But there is no certainty on who really owns them. Ask one expert and the answer will be Vietnam has the strongest claim. Ask another and the reply will be China.

What is unmistakeable is that the Paracels have been in Chinese hands for 45 years.

As Beijing increasingly claims almost all of the South China Sea as its territory, and seeks to be the supreme influence on resources and access in this region and beyond, Hanoi is getting fed up.

Conflict rooted deep in history

If anyone in Vietnam knows the significance of the Paracel Islands Museum, it’s Tran Duc Anh Son.

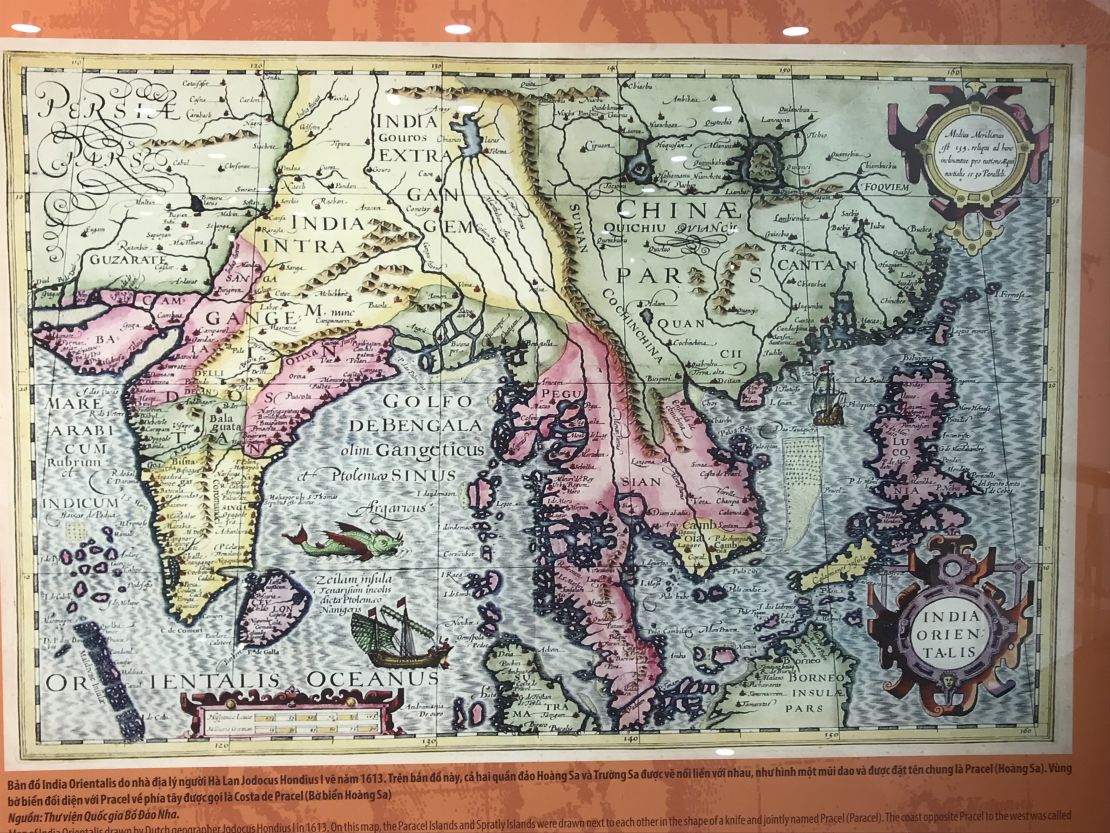

One of the country’s preeminent South China Sea experts, he helped curate the materials at the museum, including what he says is the earliest evidence of Vietnamese sovereignty over the Paracels: a map from 1686, which shows the islands as belonging tothe Nguyen Dynasty, which ruled much of what is now modern Vietnam.

In the late 17th century, the Nguyen Dynasty dispatched a fleet of fishermen, the Đội Hoàng Sa, “to occupy those islands and harvest edible bird’s nests and seafood to be brought back to the lords,” Anh Son says.

Those fishermen gave the islands their Vietnamese name: the Hoang Sa Archipelago. In 1816, King Gia Long, of the Nguyen Dynasty, formally annexed the Paracels, establishing Vietnam’s sovereignty, Anh Son says.

But China says its claims to the islands can be traced back thousands of years.

“Chinese activities in the South China Sea date back to over 2,000 years ago. China was the first country to discover, name, explore and exploit the resources of the South China Sea Islands and the first to continuously exercise sovereign powers over them,” the country’s Foreign Ministry said in a 2014 paper.

China calls the Paracels the Xisha Islands.

Experts say it’s more complicated than who named or mapped the area first.

Mark Hoskin, a researcher at the Center for International Studies and Diplomacy at the University of London, says independent records from as early as 1823 show Chinese vessels and fishermen in the Paracels.

And legally, says Hoskin, Vietnam may have given up any claim to the Paracels in 1958, when the then-Prime Minister of North Vietnam wrote a letter to the Chinese government saying that Hanoi “recognizes and approves” Beijing’s claims of sovereignty over the South China Sea and its territories.

But others give the legal nod to Vietnam, including Raul Pedroza, a former professor of international law at the US Naval War College.

Pedroza argues in a 2014 analysis for the CNA non-profit research organization that Vietnam showed clear interest in sovereignty over the Paracels from the early 1700s onward, and maintained it through French colonial times in the first half of the 20th century, and the 1954 division and subsequent unification in 1975 of Vietnam.

China didn’t show real interest in sovereignty until 1909, when it sent a small fleet of naval ships to inspect and place markers on some of the islands, Pedroza argues.

Even then, Chinese people didn’t live there until China’s occupation of Woody Island – the largest land mass in the Paracels – in 1956 and the rest of the archipelago in 1974 after a brief, but bloody, fight with then-South Vietnamese forces. But China’s actions in both cases were in violation of the United Nations charter barring force to threaten another nation’s territorial integrity, Pedroza claims, and not valid to assert sovereignty.

The 1974 fighting, in which 53 South Vietnamese troops were killed, is highlighted at the Paracels Museum, with a map detailing the battle, images of the ships involved and pictures of those who died, with testimonials saying they “gave their lives to protect every inch of their Fatherland in the open sea.”

Of course, the Chinese version of events is that Beijing was taking back what rightfully belonged to China.

Since ousting the last Vietnamese troops from the Paracels in 1974, China has been steadily fortifying its claim to the islands putting military garrisons on them and building an airfield and artificial harbor on Woody Island. Earlier this summer, China deployed J-10 fighter jets to the island, a signal to the region that “it is their territory and they can put military aircraft there whenever they want,” said Carl Schuster, a former director of operations at the US Pacific Command’s Joint Intelligence Center.

“It also makes a statement that they can extend their air power reach over the South China Sea as required or desired,” Schuster said.

And in Da Nang, just 375 kilometers directly west of the Paracels, that rankles.

Signs the problem is not going away

Outside the Paracel Islands Museum sits the 90152 TS fishing boat.

At first glance, it doesn’t look much different from some of the other boats being repaired along the coastal highway. But inside the museum, visitors learn its story.

Sunk in 2014 during a confrontation with a Chinese maritime surveillance vessel near the Paracels, its crew was later rescued by another Vietnamese boat. But the symbolism of that conflict remains strong.

“90152 TS is evidence of accusations of China’s unruly actions,” a spokesperson for the museum said in an email, explaining how the larger, steel-hulled Chinese ship easily overwhelmed the smaller, wooden Vietnamese one.

The boat is a symbol of Vietnamese “determination” to protect its sovereignty over the islands, the spokesperson added.

Beijing’s version of the 90152 story is different.

According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, the Vietnamese vessel had been “harassing” a Chinese fishing boat in waters near the Paracels. Xinhua reported at the time that the Vietnamese boat overturned after it “jostled” a Chinese fishing boat.

It’s the kind of incident that highlights how quickly things can blow up in the South China Sea.

As China pushes its claims to territory in the sea, it has built up and fortified islands in the Spratly chain – which has claims by Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines – while earlier this year it swarmed boats and ships around the Philippine-controled Thitu Island.

And in an incident similar to the 2014 case, a Philippine fishing boat sank after colliding with a larger Chinese boat in early June. Reports in Chinese state media said the Chinese boat hit the Philippine boat as it moved quickly out of the area because its crew felt threatened by seven or eight Philippine boats which had “besieged” it while fishing.

But Philippine media rejected those, saying the bigger Chinese boat was trying to intimidate the Philippine ones.

Philippine Daily Inquirer columnist Richard Heydarian said it was indicative of “China’s rise as an increasingly brazen regional hegemon.”

He called China’s fishing fleet “the tip of the dagger of Beijing’s efforts to dominate adjacent waters.”

Meanwhile,the South China Sea face-off between Vietnam and China flared again this summer, when a Chinese survey ship and its escorts encroached inside Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone – the 200-mile area from a country’s shore where it has exclusive mineral rights – in the Spratlys.

The area is believed to hold substantial gas and oil deposits, which Vietnam is trying to develop.

Leaders in Hanoi made their displeasure clear, with the Foreign Ministry on July 19 calling on all Chinese ships to leave Vietnamese waters.

Analysts say China’s actions are worrisome.

“Beijing is testing not only Vietnam, but also the United States and the international community,” Huong Le Thu, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, wrote in an analysis this month.

China’s aggressions in the South China Sea are tests from Beijing to see how far all countries will go into supporting “the rules-based order,” she wrote.

What can Vietnam’s island push accomplish?

With its superior military and financial resources, China seemingly holds the upper hand in the fight for the South China Sea. Hanoi’s quest for the Paracels may be more quixotic than practical.

“It’s a bit of a mystery to me,” said Bill Hayton, an associate fellow in the Asia-Pacific Program at Chatham House in London. “Does the Vietnamese Communist Party really expect to get the islands back? Do they expect to maintain the population on the edge of nationalist hysteria indefinitely?”

Ben Bland, research director of the Southeast Asia project at Australia’s Lowy Institute, says Vietnam is employing a “use or lose it” practice. “Governments are keen to show they are administering these territories as a way to support or build a deeper framework around their territorial claims,” Bland says.

And there are more subtle ways to build claims, he said. Such as a museum.

But there seems to be little room for subtlety in the Paracel Islands.

“The reality on the ground is that China has occupied the entire Paracel group for 40 years and, short of military action by Vietnam to recapture the archipelago, will never leave,” CNA senior fellow Michael McDevitt wrote.

And that puts a limit on Hanoi’s options.

“Neither party is willing to risk war to force the issue to conclusion. The territorial claim is a journey without end,” according to Hayton.

Anh Son, the Vietnamese expert, agrees.

“We can’t start a war with China because that would be absolutely devastating for our people,” he said. “I know that China won’t yield easily, but filing a case against them before the International Tribunal is the only solution at the moment.”

The street view

Vietnam is not limiting its propaganda campaign to just the Paracel Islands Museum.

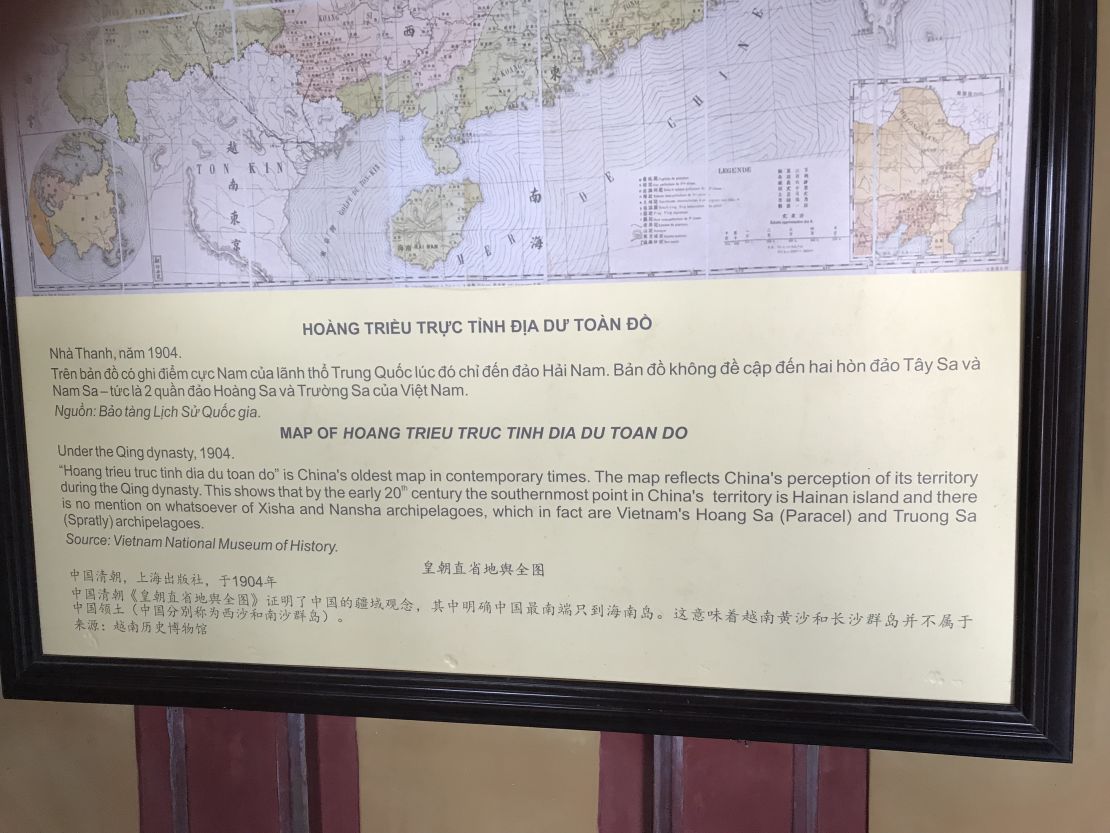

At the Imperial City in Hue, one of Vietnam’s premiere tourist attractions in the historical capital a few hours’ drive north of Da Nang, there’s a display of what Vietnam calls “China’s oldest map of contemporary times.”

“This shows that by the early 20th century, the southernmost point in China’s territory is Hainan island and there is no mention whatsoever of Xisha and Nansha archipelagoes which in fact are Vietnam’s Hoang Sa (Paracel) and Truong Sa (Spratly) archipelagoes,” a caption on the large wall display reads.

Meanwhile, on the Da Nang beachfront, the road is busy with traffic. Visitors cross its multiple lanes, which are unregulated by traffic lights, in a ballet where the cars and scooters barely slow down as the pedestrians daintily dart across the highway unscathed.

A sign says the beach is called My Khe, but some tourist maps and guides refer to it as “China Beach.”

That was the nickname given to it by US soldiers, for whom it was a rest-and-recreation stop.

But Vietnam’s government chafes at the term and threatened to close domestic travel websites that use it.

Many locals don’t take kindly to it, either.

On the TripAdvisor website, one Vietnamese user responds to a question, “where to find China Beach?”

“Don’t have any China Beach in Vietnam!” it says, telling the questioner if they want to find a China Beach they should go to China.

The sentiment carries over to the beach itself on a July morning.

“Don’t call it that,” says one local, who asked not to be named, when questioned about the moniker. It just “encourages” Beijing’s infringement on Vietnam’s territory.

He acknowledges the effect of those maps, the museum up a few kilometers up the beach, the Vietnamese government’s unyielding stance on the Paracels.

They are part of Vietnam, and eventually, they need to come back some way.

“Today we keep the peace,” he says. “Tomorrow, who knows?”

CNN’s Dan Tham contributed to this report.