No one predicted this.

When the final protesters were cleared from Hong Kong’s streets after 79 days of pro-democracy protests in 2014 – many of them forcibly carried off by police – they promised they’d be back.

For years this seemed like a pipe dream. The Umbrella Movement, so-named in reference to the umbrellas used by protesters in defense of police pepper spray, changed Hong Kong forever.

The movement awoke a whole generation of new activists and politicians, some of whom would go on to be elected to the city’s legislature, but in many ways it felt like a failed last stand, with everything that came after it seeming more like a desperate rear guard action against ever-increasing Chinese influence and control over the semi-autonomous city.

Protest leaders who were elected were expelled from office on dubious grounds, and many others were arrested and jailed for their part in the unrest. Demonstrations and marches never attracted the numbers seen in 2014, and it seemed like the pro-democracy movement was on life support.

Now, four years, eight months and 12 days after the Umbrella Movement ended, ongoing protests have surpassed it in duration and massively overtaken it in terms of disruption and political turmoil – and they show no signs of stopping.

The roots of the current unrest can be traced back to that summer five years ago, both in the radicalizing effect it had on a whole generation of young Hong Kongers and in the government’s failure to do anything.

With the collapse of the protest movement in December 2014, a lid was placed on the disruption, leaving the underlying frustrations boiling and ready to explode.

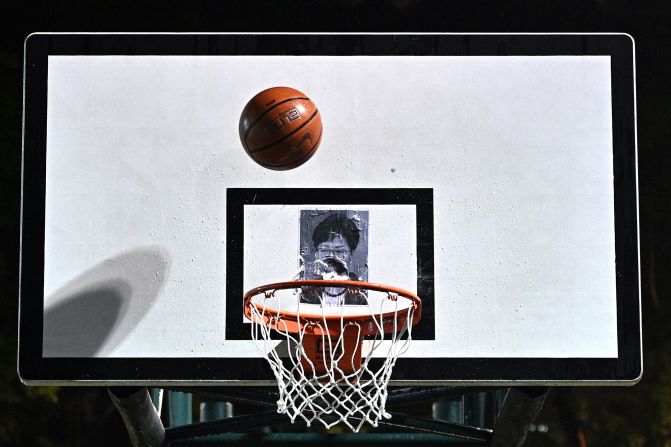

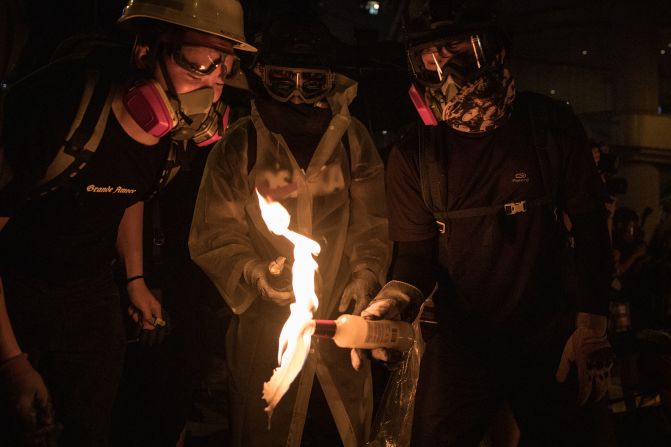

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

The political roots of the current unrest

The current protests – they don’t have an agreed upon name but the snappiest is the “Hard Hat Revolution” for the yellow helmets many protesters wear to protect against police weapons – began on June 9, when organizers say more than a million people attended a protest march calling for the withdrawal of an extradition bill with China.

The bill was eventually suspended following violent clashes between protesters and police outside the city’s legislature on June 12 and an even bigger march the following weekend, which saw the largest ever turnout at a protest in Hong Kong’s history – but for many the suspension was too little too late.

As the protests enter their twelfth week, overtaking the Umbrella Movement in duration, the complete withdrawal of the bill remains a key priority, but protesters have also expanded their demands to include the driving issue of the 2014 protests: Genuine universal suffrage in how the city picks its leader.

When Hong Kong was handed over from British to Chinese control in 1997, it switched from having a London-picked governor to a local Chief Executive, selected by an “election committee” and officially appointed by Beijing. Per the Hong Kong constitution, the ultimate aim is for the city’s leader to be elected “by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures” and the election of all members of the legislature – which is currently about 50% democratically elected – “by universal suffrage.”

In the more than two decades since 1997, reform has been slow coming. Carrie Lam, the current chief executive, is the fourth person to hold that office, none of whom were elected by universal suffrage.

In 2007, China’s top lawmaking body agreed that the contest which eventually resulted in her appointment “may be implemented by the method of universal suffrage; that after the Chief Executive is selected by universal suffrage, the election of the Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region may be implemented by the method of electing all the members by universal suffrage.”

Seven years later, however, China’s leaders ruled out full universal suffrage, saying that candidates could be elected by the public – but only after they had been approved by a Beijing-dominated nomination committee. Most democratic activists and lawmakers rejected the deal as a sham and it was eventually defeated in the city’s legislature after a botched walkout by pro-government legislators.

In the interim, hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers occupied parts of the city for 79-days, demanding Beijing withdraw its decision and allow the chief executive to be elected by “genuine universal suffrage.”

After the use of tear gas in the early hours of the protests backfired spectacularly, bringing more people to the streets, authorities took a largely hands-off approach, and the Umbrella Movement had gradually fizzled out by the time police cleared the last dedicated protesters in December 2014.

Hong Kong’s wealth gap is a major cause of protests

While the movement did not achieve its main goals, the influence of the protests was massive. Legislative elections in 2016 returned the youngest, most politically radical parliament the city had ever seen – though several lawmakers were later ejected from office – and the protests are also widely credited with hastening the end of former Chief Executive CY Leung’s career.

Lam, Leung’s former deputy and now successor, refused to consider restarting political reform after she took office in 2017, choosing instead to focus on livelihood and economic issues.

This wasn’t necessarily a bad idea. Hong Kong is one of the most unequal cities in the world; housing prices and living costs rise each year, while youth employment rates have been largely stagnant and many young graduates struggle to find work.

Inequality is linked to the desire for greater democracy, which is driven in large part by an understanding that the city’s leader and legislature – where around 50% of seats are appointed by industry bodies and other non-democratic groupings – are more responsive to the whims of Beijing and local elites than they are to the wider public.

“The government should take from the rich and give to the poor so they can live in Hong Kong, too,” Tse Lai-nam, a 26-year-old who has taken part in the recent protests, told CNN this month. “The government has never done anything to promote social mobility, instead it has increased wealth disparity and made it more difficult for young people to buy an apartment.”

Lam’s proposals to remedy these issues have largely fallen flat. Her most ambitious plan, to build a 17 square kilometer (6.5 square mile) cluster of artificial islands off Lantau at a cost of around $80 billion, has faced criticism and protests from local residents, environmentalists and opposition lawmakers. In particular, many point out that it does not address immediate concerns, with the first group of houses built on the islands not expected to be available until at least 2032.

Other proposals to relieve the pressure on poorer Hong Kongers have fallen equally flat. Lam also attracted outrage – and renewed criticism for being out of touch – when she defended plans to raise the age limit for elderly welfare payments by saying “I am over 60-years-old but I still work for over 10 hours every day.”

Less than 50% of over-60s in the city are employed. Lam makes around $635,000 a year and does not pay for her own housing. Hong Kong is no way strapped for cash, it has some $1.12 trillion in reserves, and has posted budget surpluses every year for the last decade.

But this has largely not translated into the type of big ticket livelihood reforms and improvements Lam promised on taking office. Instead her administration has chosen to give cash handouts – $510 last year for around 2.8 million people – that while appreciated by their recipients, did little to address the underlying issues.

Protesters changed their tactics, officials are stuck in the past

In retrospect, a storm was clearly brewing. While Lam has so far failed to alleviate Hong Kong’s yawning inequality, she has also continued her predecessor’s policy of cracking down on Umbrella Movement leaders and moving closer to China.

A controversial bill giving mainland Chinese authorities joint control over the city’s new high-speed rail terminus, raised significant alarm, as did plans to adopt a Chinese law banning insult of the Chinese national anthem and flag.

Multiple Umbrella leaders, including Joshua Wong and Benny Tai, were imprisoned under Lam’s administration, and some more radical pro-democracy activists were barred from standing for election.

On the other side of the border, the situation continued to worsen, as Chinese President Xi Jinping secured power for life and cracked down on dissent. In the far-western region of Xinjiang, millions of Muslims have reportedly been detained in “re-education” camps, and numerous activists have been jailed or disappeared.

All of this tension and anger was a tinder box waiting to be lit by the extradition law. When the government failed to respond to a huge protest march on June 9 and pressed ahead with a second-reading of the bill days later, it exploded. Attempts by Lam to get the genie back in the bottle have proven unsuccessful, as the protests have outpaced her.

Unlike the government, protesters have learned from 2014. Rather than an exhausting, drawn-out occupation requiring people to camp out in the streets for weeks, making them vulnerable to police, counter-protesters and Hong Kong’s often miserable weather, they have instead adopted Bruce Lee’s slogan “be water.” A variety of protests, marches and strikes have taken place in the past months, evolving with the police and government response and impacting neighborhoods some of which had never seen a major protest before.

“If this was an occupation on the streets every day it wouldn’t have lasted anywhere near this long,” Wong told CNN this week.

Another key change has been in the leaderless nature of the protests. While this has its issues – most notably an inability to deescalate in violent or out-of-control situations – it has left the authorities without obvious targets for arrest. Some have argued that this also means there is no one for the government to negotiate with, but as Wong and others have pointed out, of five student leaders who met with Lam and other top officials in 2014, three were later jailed.

Following a rare tear gas free weekend earlier this month, Lam gestured towards future reconciliation, saying she would launch an “important fact-finding study” into the causes of the protest.

“I hope that this is a very responsible response to the aspirations for better understanding of what has taken place in Hong Kong,” she said. “And most important of all, it is not just fact finding to provide the sequence of facts. It also will provide the Government with recommendations on how to move forward and also to avoid the recurrence of similar incidents.”

For many Hong Kongers, the problems the city suffers were clear before the 2014 protests brought them to the attention of the world, and were even clearer afterward. That Lam’s government still does not apparently understand, or have any plan to address them, could mean the current unrest continues another 79 days.