Despite outbreaks of flu, tuberculosis and chicken pox, US Customs and Border Protection refuses to tell the public how many migrants in detention facilities have contagious diseases.

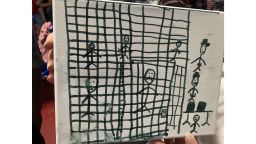

Doctors have long been concerned that these congested settings are breeding grounds for serious illnesses.

“They create facilities that encourage the spread of infectious agents,” said Dr. William Schaffner, an adviser to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on vaccine issues.

A CBP senior health official told CNN his agency keeps track of infectious diseases among the hundreds of thousands of migrants who pass through CBP detention facilities but declined to release that data.

This stands in stark contrast to how other entities handle disease statistics. State and county health departments across the United States track ongoing case counts for dozens of infectious diseases and make that information available online. Similarly, the United Nations posts disease statistics about refugees online.

Public health experts sharply criticized CBP for what they called the agency’s lack of transparency.

“What are they scared of?” asked Dr. Paul Spiegel, a former senior official at the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who is now the director of the Center for Humanitarian Health at Johns Hopkins University.

He said making such information available is crucial to public health.

“In health, we measure things, and the more people who know that information, the better,” he said. “Migrants are released into the community and quickly move to other places in the country.”

The CBP official said his agency reports illnesses to state health departments.

“We do share this information. We’re not hiding it,” he said.

However, CNN’s review of the deaths of three children who had the flu and died while in CBP custody or shortly after raises questions about whether infectious disease data on migrants is consistently reported to state health officials.

In addition, a review of state health department websites indicates that disease data on migrants is not available to the public, which would include researchers and physicians.

Public health transparency

In the first seven months of 2019, more than 600,000 migrants were apprehended crossing the US southwest border. CBP policy, rooted in legal agreements, aims to move both children and adults out of its custody within 72 hours.

Government reports show, however, that both children and adults have been held for considerably longer than 72 hours.

“We’ve seen everything from mumps, chicken pox, flu, and tuberculosis,” a CBP spokesperson wrote in an email to CNN.

The spokesperson and the agency’s senior health official, both of whom spoke on the condition that their names not be used in this report, declined to provide a full list of infectious diseases observed in migrants, or the number of cases or deaths from those diseases.

Spiegel, the former UN official, said that’s unfortunate because when the United Nations released health surveillance data online, public health researchers could then analyze the data and offer important insights.

“We had people all over the world look at this data and write papers on it, and it was helpful,” he said. “The more data that’s out there, the better.”

Dr. Jonathan Winickoff, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, added that such transparency also helps doctors in the area aid migrants and the surrounding population.

“There’s a reason why numbers are reported and made public, and that’s so clinicians and public health responders in those locations can understand the nature of the risk and take appropriate actions and make sure the public is protected,” Winickoff said. “When the numbers are invisible, it’s very hard to take protective action.”

Doctors urge CBP to vaccinate children

One of the most important protective actions is to vaccinate migrants, Winickoff said.

Earlier this month, Winickoff, Spiegel and three other physicians sent a letter to members of Congress expressing concern about infectious diseases at migrant detention centers. Detailing the deaths of three children in US custody who died after contracting the flu, the doctors urged that migrant children be vaccinated against the virus.

According to a CBP statement, the agency doesn’t vaccinate migrants “due to the short-term nature of CBP holding and the complexities of operating vaccination programs.”

Winickoff and Spiegel said that argument doesn’t make sense to them. They said it’s relatively quick and inexpensive to vaccinate even large groups of people. The doctors said vaccination helps protect migrants and the people around them as they move out of CBP facilities and into other government facilities or into the US community at large.

Spiegel said the UN refugee agency, where he worked for 15 years, oversaw programs that vaccinated millions of refugees soon after they crossed international borders.

“If we can do it in places like Darfur and South Sudan, I imagine the US government can do it,” he said. “Frankly, it’s not so hard and it’s not so complicated.”

Reporting migrant illnesses and deaths

The CBP senior health official said his agency shares health surveillance data with the four state health departments along the southwest border.

“We do share that information and record and coordinate through the established public health channels,” he said. “We do share this information.”

When asked what diseases CBP reports to state health departments, the official said it depends on the laws of that particular state.

“Obviously every case of scabies doesn’t need to be reported or raised,” he said.

In Arizona, however, outbreaks of scabies – a skin infestation where mites burrow under the skin – is required to be reported.

Nationwide, pediatric flu deaths are required to be reported to state health authorities. But it appears the deaths of two out of the three migrant children who had the flu and died were not reported to state health departments.

8-year-old Felipe Gomez Alonzo died in December in New Mexico after contracting the flu. But according to the New Mexico Department of Health, there were two pediatric flu deaths in the 2018-2019 flu season – one child was 16 and the other was 1 year old.

2-year-old Wilmer Josue Ramirez Vasquez died in May in El Paso after contracting the flu. The Texas Department of State Health Services reports no pediatric flu deaths in that region of the state during the 2018-2019 flu season.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

16-year-old Carlos Hernandez Vasquez died in May in Hidalgo County, Texas after contracting the flu. It’s unclear if his death is included among the five pediatric flu deaths that occurred in that region of the state during the 2018-2019 flu season.

Doctors said publicly reporting infectious diseases and deaths is crucial to protecting public health.

“It matters deeply to make sure that others are not infected,” Spiegel said. “The public needs to understand what’s going on in these facilities.”