When humans are habitually exposed to cold water and air, “surfer’s ear” can be one of the consequences – and apparently, the same was true of Neanderthals. But it’s less likely that they experienced bony growths in their ear canals due to surfing.

The dense growths are known as external auditory exostoses. They occur more frequently in men, and even though the growths are often benign, they can lead to hearing loss. They’ve been found in ancient human remains before, but there hasn’t been much investigation into how lifestyle may have contributed to the cause.

Scientist Pierre Marcellin Boule discovered the first relatively complete Neanderthal skeleton and reconstructed it in 1911, noting that the remains included these bony growths in the auditory canals. But he didn’t follow up the observation with further study.

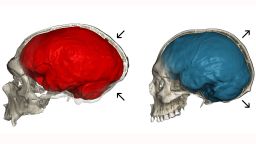

A study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE includes the analysis of 77 ancient human ear canals. The well-preserved remains came from Neanderthals and early modern humans who lived in western Eurasia during the Middle and Late Pleistocene.

The surfer’s ear cases in early modern humans were similar to human cases today.

But the researchers were most surprised by how common the condition was in Neanderthals. Half of the 23 Neanderthal samples showed signs of the bony growths, ranging from mild to severe. This was twice the amount they observed in any other group.

How exactly would Neanderthals get “surfer’s ear”? The researchers believe the best explanation is that they lived or foraged for resources in aquatic settings.

But that answer may not entirely depend on how close Neanderthal populations lived to ancient water sources or in cold climates. Because of this, the researchers suggest that multiple factors were involved, including environment and genetic predisposition. In modern humans, there is a predisposition for the condition based on genetics.

“An exceptionally high frequency of external auditory exostoses among the Neandertals, and a more modest level among high latitude earlier Upper Paleolithic modern humans, indicate a higher frequency of aquatic resource exploitation among both groups of humans than is suggested by the archeological record. In particular, it reinforces the foraging abilities and resource diversity of the Neandertals,” said study author Erik Trinkaus, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University.