Hong Kong was hit by widespread strikes Monday that brought chaos to much of the city’s transport network, including Hong Kong International Airport, in the most ambitious day of demonstrations since the movement began in June.

More than 2,300 aviation workers joined the strike, according to the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, leading to the cancellation of 224 flights to and from one of the world’s busiest airports. The airport was packed with unusually long lines, and its air space and runway capacity was reduced by 50%.

Experts said Monday’s strikes were the biggest to have rocked the city in decades.

Direct action protests also took place in seven districts: Admiralty, Sha Tin, Tuen Mun, Tseun Wan, Wong Tai Sin, Mong Kok and Tai Po. Organizers also called for a general strike at Disneyland and the airport, both on Hong Kong’s Lantau Island.

Strikers included teachers, lifeguards at beaches, security workers, construction workers – and almost 14,000 people from the engineering sector.

Monday’s strike followed the ninth consecutive weekend of protests in Hong Kong amid a worsening political crisis. The protests began in early June in opposition to a controversial – and now-shelved – bill that would have allowed extradition to mainland China.

But they have since evolved to include calls for greater democracy, an inquiry into alleged police brutality and the resignation of the city’s leader, Carrie Lam, among other demands.

Biggest strike of its kind in decades

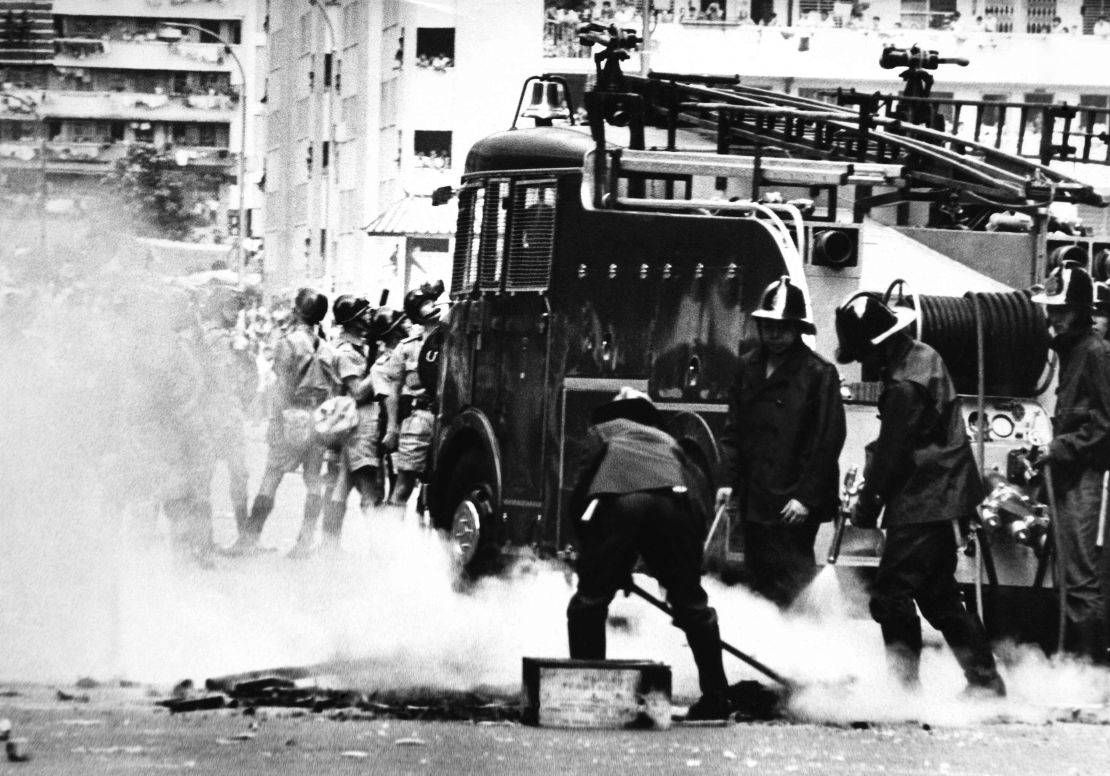

Monday’s general strikes are believed to be the first of their kind since 1967, when a Chinese Communist Party-allied union instigated widespread labor protests – which were followed by deadly terror attacks in which 51 people died.

Antony Dapiran, a lawyer and Hong Kong historian, said Monday’s strikes are likely the biggest in the city since those in 1967, when Hong Kong was still a British colony. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” he said.

“We’ve had rallies in Hong Kong before, we’ve had protests, but we’ve never had anything where multiple sites around the city have all simultaneously have been the focus of protests,” said Dapiran, author of “City of Protest: A Recent History of Dissent in Hong Kong.”

John Carroll, a historian at Hong Kong University, agreed that Monday’s strikes were unprecedented in scale and organization in the city’s modern history. He said that the best parallel with Monday’s action was probably the 1925 general labor strike, which lasted for months. The 1967 strike was different to Monday’s unrest, he said, because many workers were living in fear of going to work due to terrorist bombings across Hong Kong.

“I have no idea where it goes,” Carroll said of Monday’s action. “But it’s hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel here.”

Fresh clashes and international response

Monday’s strikes followed a morning of transport chaos as demonstrators disrupted major transit routes across the city in the fifth day of protests in a row.

Major subway lines were suspended or delayed during rush hour as protesters blocked trains from leaving stations. An average of 4.84 million passengers ride the subway every day, according to the Hong Kong Transport Department – more than half of the city’s population.

Protesters also blocked roads and highways, including the Cross-Harbour Tunnel, a vital traffic artery connecting Hong Kong island with Kowloon.

As the afternoon wore on, clashes between protesters and police broke out across the city and police fired tear gas in five districts – Tin Shui Wai, Admiralty, Wong Tai Sin, Tai Po, and Tsim Sha Tsui.

In Tin Shui Wai and Wong Tai Sin, the tear gas came after demonstrators surrounded police stations and hurled water bottles and rocks at officers. Tin Shui Wai in particular is a charged location – it’s right next to the far northern suburb of Yuen Long, where an armed mob attacked civilians in a subway station last month and injured at least 45 people.

Admiralty is also a significant site – it’s home to the Legislative Council building, which protesters stormed and trashed on July 1. On Monday, thousands of protesters blocked the Admiralty roads, to which police responded by firing tear gas from a balcony onto the street.

The clashes have also attracted international attention – United States House Speaker Nancy Pelosi released a statement on Monday in support of the protesters, hailing their “dreams of freedom, justice and democracy.”

“The extraordinary outpouring of courage from the people of Hong Kong stands in stark contrast to a cowardly government that refuses to respect the rule of law or live up to the ‘one country, two systems’ framework which was guaranteed more than two decades ago,” Pelosi said in the statement.

Pelosi isn’t the only US politician to have spoken out about the protests – so have several members of Congress, who have also introduced a bill backing democracy in Hong Kong.

These statements are likely to fuel accusations from mainland China that the US is influencing the protests.

“As you all know, they are somehow the work of the US,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said of the protests just last week.

Hua added that China would “never allow any foreign forces” to interfere in the semi-autonomous city, and warned that “those who play (with) fire will only get themselves burned.”

The comments are one of the most direct accusations Beijing has so far made of US interference in Hong Kong politics – though it has not yet provided any evidence for the allegations.

1,000 rounds of tear gas, 160 rubber bullets, 420 arrests

In recent weeks the protests have become increasingly violent and unpredictable.

On Saturday, marches began in the densely-populated Mong Kok, before veering off the police-approved protest route – turning the march into an illegal assembly.

Then on Sunday, protesters vandalized a police station in eastern New Territories. Later that night, protesters blocked key roads in retail hotspot Causeway Bay, to which police responded with tear gas.

In a press conference Monday, police accused protesters of using “guerrilla tactics” to disrupt public order and said they had arrested 420 people since protests began on June 9, on charges of rioting, unlawful assembly, and attacking officers.

Since the start of the protests, police have used 160 rubber bullets, 150 sponge bullets and fired 1,000 rounds of tear gas, a police spokesperson said.

Also on Monday, Hong Kong’s leader called for an end to the violence in a press conference. She acknowledged that the extradition bill was a “failure,” but refused to resign or to release arrested protesters, saying the latter wasn’t within her power – a move that is likely to further anger protesters, who demand all charges be dropped.

CNN’s Eric Cheung, Chermaine Lee, Angus Watson and Justin Solomon contributed from Hong Kong.