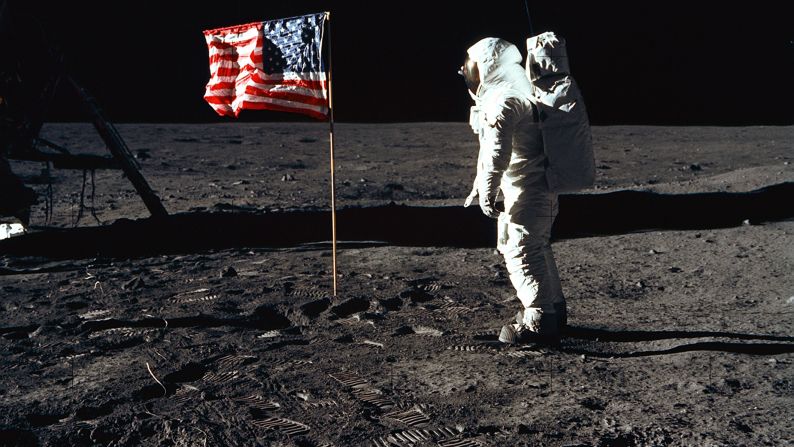

When astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the surface of the moon 50 years ago, they took photos, collected lunar rock samples and left behind an experiment that’s still sending back data.

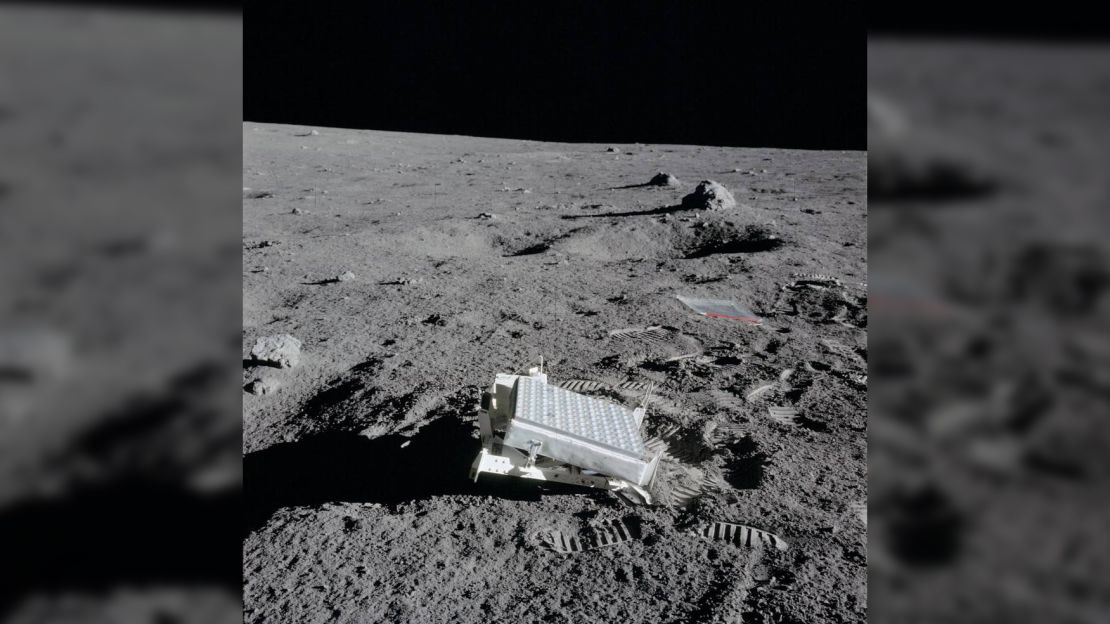

Aldrin placed an array – an arrangement of 100 quartz glass prisms in rows – on the surface. Later, the Apollo 14 and 15 missions would also add similar arrays to the surface.

The simple experiment doesn’t require any power, which is why it’s still serving a purpose.

The arrays reflect light, which is full of valuable insight, back towards Earth. Observatories in Italy, France, Germany and New Mexico regularly aim lasers at the arrays and note the time it takes for the light to return to Earth, according to NASA.

Scientists can measure that distance down to a few millimeters. This allows researchers to determine the moon’s orbit, rotation and its current orientation, which will be needed to land on the moon. They also act like mile markers for the cameras attached to spacecraft.

Although we know that the moon is about 239,000 miles away, the arrays allowed scientists to determine that this distance actually increases by an inch and a half each year.

Previously it was believed that the moon had a solid core, but data from the arrays has revealed that the core is fluid. This core determines the direction of the lunar poles, which the array data can also help determine through orientation.

Over the next decade, new and improved reflectors will be placed in different areas on the moon to study more about the moon’s interior, a glimpse into its past and help with future exploration.

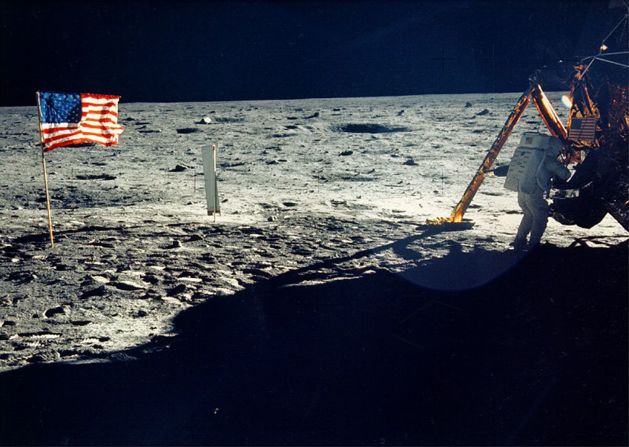

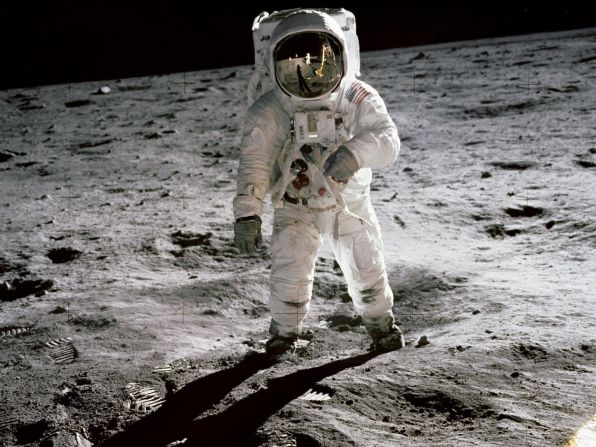

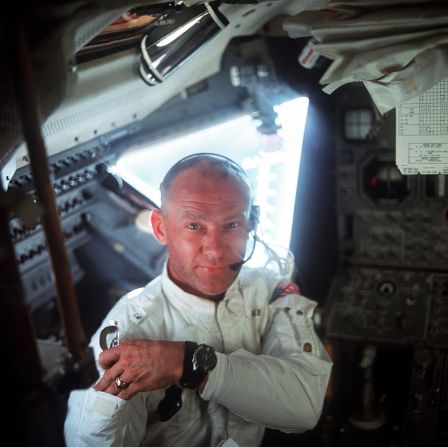

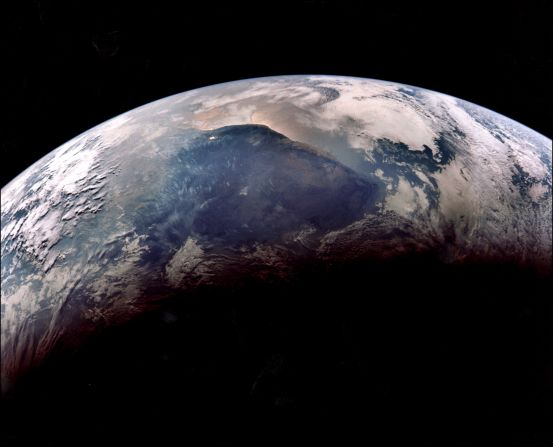

The Apollo 11 moon landing, in photos

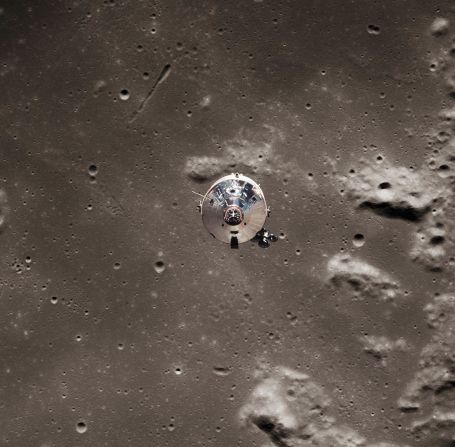

In order for NASA to even reach the moon in the first place in 1969, cameras were sent to capture detail about the lunar surface to ensure that the astronauts and anything else touching the moon wouldn’t sink down into the dust.

Until 1964, there weren’t any closeup or detailed photos of the lunar surface.

NASA’s Ranger spacecraft were designed to orbit the moon and document the surface. The first few either didn’t escape low-Earth orbit or missed the moon entirely. Others were intentionally crashed into the moon but didn’t return any images before impact.

In 1964, Ranger 7 successfully reached the moon and returned 4,316 images of the surface before it collided intentionally with the surface.

The area where it crashed was called Mare Cognitum, which is Latin for “The Sea that has Become Known.” Ranger 8 and Ranger 9 would send back thousands more images and live images of a moon crater, which would enable the next steps of lunar exploration.

NASA has created a goal of landing the first woman and next man on the moon’s South Pole by 2024. NASA has dubbed this path back to the moon Artemis, after Apollo’s twin sister in Greek mythology. The agency also wants to establish a sustained human presence on and around the moon by 2028.