Chinese authorities are using an app to collect vast amounts of data on Muslim Uyghurs, as part of a mass surveillance system in the far western region of Xinjiang, according to a report on Thursday.

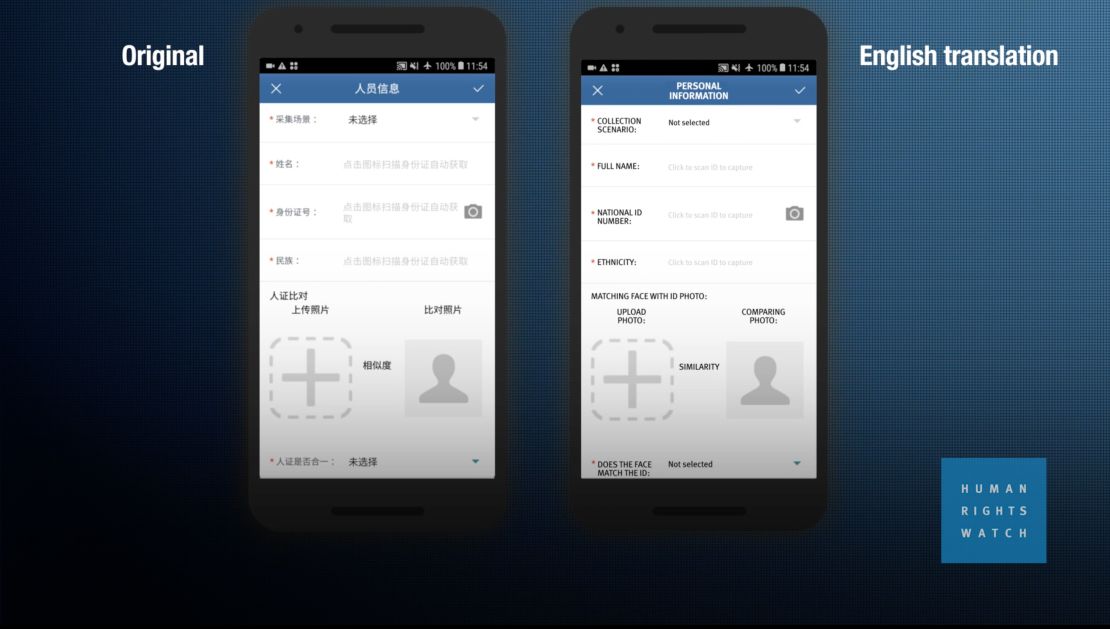

Human Rights Watch (HRW) says the app allows state security officials to link a person’s national identity card number with biometric data, such as blood type and height, their “religious atmosphere,” political affiliation and even “unusual” utility meter readings.

The app also records “suspicious” behavior, which can include legal activities such as using the back door of a home, not socializing with neighbors or buying too much gasoline.

It is linked to the all-encompassing Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), which monitors personal relationships and detects irregularities such as people using a phone that is not registered to them.

CNN has reached out to China’s foreign ministry and the Xinjiang regional government for comment.

The Chinese authorities have previously called HRW an “organization (that) has kept making false allegations on China-related issues all along.”

“With economic development, people in Xinjiang are living a peaceful and happy life, and the situation there is sound,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lu Kang in December 2017 in response to another HRW report on Xinjiang. “The Chinese government will continue to uphold the unity of people of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang, safeguard their happy life and promote progress in various fields of Xinjiang.”

36 types of suspicious people

As many as two million Muslim-majority Uyghurs are believed to have been imprisoned inside massive detention centers in Xinjiang, according to the US State Department, where they are allegedly taught Mandarin and Communist Party propaganda.

In recent years, activists have accused the Chinese government of “cultural genocide” against minorities in Xinjiang.

Authorities have banned long beards and veils in the region and government officials have forced homestays on Uyghur families, with the officials monitoring families for “suspicious” activities such as avoiding alcohol and pork. A heavy police presence is omnipresent in Xinjiang’s large cities.

The HRW report sheds light on how technology is playing an increasingly important role in that crackdown – and questions the legality of it.

“Our research shows, for the first time, that Xinjiang police are using illegally gathered information about people’s completely lawful behavior – and using it against them,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher at HRW.

“The Chinese government is monitoring every aspect of people’s lives in Xinjiang, picking out those it mistrusts, and subjecting them to extra scrutiny.”

The rights group says it reverse-engineered the a copy of the app to understand how it worked. Doing that enabled HRW to learn the specific behaviors and 36 types of people the system was targeting, it claims.

The app connects to the IJOP – the region’s huge security apparatus, which uses facial recognition and aggregated data about Xinjiang residents – and “flags those deemed potentially threatening,” HRW says.

It claims that sophisticated checkpoints – so-called “data doors” – can identify citizens not only through facial recognition and ID cards, but can also “vacuum up people’s identifying information from their electronic devices” through their mobile phone MAC addresses and IMEI numbers. These are used “for identification and tracking purposes.”

The wider IJOP system has been developed by the state-owned China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, described by the rights group as a “military contractor.”

The app was developed by the Hebei Far East Communication System Engineering Company, which was wholly owned by the government at the time. ailable data and found how extensive its reach was.

CNN has reached out to Hebei Far East Communication System Engineering Company and China Electronics Technology Group Corporation but did not immediately hear back.