South Korea’s entertainment industry is a cultural juggernaut that has allowed the East Asian nation to punch well above its weight in terms of global soft power.

But a digital sex scandal that police say involves some of K-Pop’s biggest stars has rocked the K-Pop world, leaving it facing a reckoning from which some believe it might not recover.

In the past month, four major K-Pop idols have apologized or announced early retirement after being linked to a group chat in which members shared sexual videos of women who were allegedly filmed without their consent. On Thursday, singer Jung Joon-young was arrested in connection with the scandal.

The allegations tie in with a wider problem in South Korea of illicit recordings and voyeurism.

This week it emerged that about 1,600 people had been secretly filmed in motel rooms in South Korea. Police say the footage was live-streamed online to paying viewers. Last year, in Seoul, a squad of women inspectors was deployed to search the capital’s 20,000 or so public toilets for spy cameras.

K-Pop stars have long been placed on pedestals, with management companies highly protective of their squeaky clean images.

Allegations linking some to the dirty world of online voyeurism have rocked South Korea, and exposed how the longstanding problem of toxic masculinity – the idea that the male role involves violence, dominance and devaluing women – has penetrated every level of society.

Speaking at a protest Thursday over the scandal, Kim Yong-soon, co-president of Korean Women’s Association United, said “the rape culture (in Korea) that has used women for erotic videos has been maintained for a long time.”

“The male-centered … rape culture did not stop even after feminism and the growth of the feminist movement and #MeToo,” she said, adding now there was an opportunity “to sort out finally the male-centered culture that has traded women’s sexuality (for so long).”

At an emergency meeting with concerned groups and activists this week, South Korea’s Minister of Gender Equality and Family Jin Sun-mee had a simple message for the country’s men.

“Please stop,” Jin said. “Please report it. Women are humans with souls who can be our colleagues, friends or sisters who live and breathe next to us.”

Toxic masculinity

When South Korean police depicted a spy cam voyeur in a public awareness campaign designed to protect women, amid an epidemic of voyeurism and upskirt photography, their typical perpetrator couldn’t have looked less like a K-Pop idol.

The posters showed an overweight, rosy-cheeked man dressed like a child in suspenders and shorts.

Police apologized, and the campaign was quickly withdrawn, deemed wildly inaccurate and offensive to the millions of women living in fear of illegal filming. There is little evidence to suggest spy cam operators and upskirt snappers are badly socialized losers rather than regular men brought up in a society that has taught them to see women as objects.

The latest allegations bear out that reality. The accused K-Pop stars are famous young men at the height of their industry, feted in the press and fawned over by millions of fans.

The sale and distribution of pornography is illegal in South Korea, and porn sites are blocked or difficult to access online. However, some men share explicit videos on messaging apps and social media, including potentially illicitly filmed footage.

“(This issue) is prevalent in every part of society,” said Choi Mi-jin, president of the Women Labor Law Support Center. “It is not just a problem with certain celebrities.”

This scandal, Choi said, exposed the way that men generally “currently perceive women.” In 2018, tens of thousands of women protested against surge in illegal filming in central Seoul under the slogan “My Life is Not Your Porn.” However, many women at the events covered their faces for fear of being identified or harassed online afterward.

Park Kwi-cheon, a labor law professor at Ewha Law School in Seoul, said that because Korean men often view women as merely sexual objects, they might not fully understand why filming a sexual partner without consent is wrong.

“For example, in colleges there have been incidents when male students would secretly take pictures of female students or disparage women sexually in group chats,” Park said. “There is a culture where they don’t think of such behavior as crimes but think of it as a kind of game.”

VIP scandal

K-Pop labels and management companies begin the development of some artists from an early age, said Jung Duk-hyun, a pop culture expert. Recruited into K-Pop training camps, the future stars are highly controlled and molded to be as close as possible to perfect performers in both voice and look.

While undergoing as much as a decade of pop-star training, some artists are cut off from society, as they focus on working their way up the ranks of a K-Pop stable, hoping to one day burst onto the music stage. When they do go public, artists are often forbidden by their contracts from dating for several years, in part, some experts say, to appease fans who dream about dating their idols.

That transition from isolation to sudden fame creates fertile soil for misbehavior and a pronounced power imbalance between artists and fans, Jung said. The limiting conditions of the contracts stars sign with the labels can also create skewed expectations of how stars should act.

Stars can go from relative nobodies to widely recognized figures overnight, with no anonymity, leading them to seek refuge in places like dark and isolated VIP rooms of bars and clubs, Jung said.

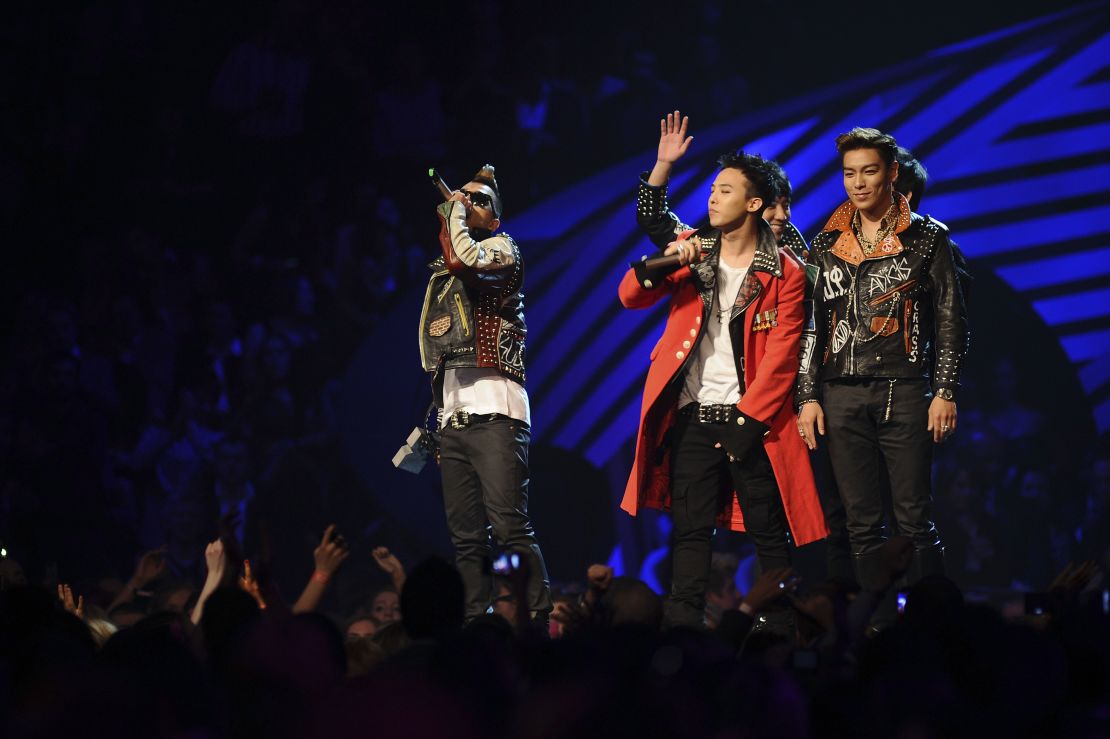

Burning Sun, a popular nightclub in the upmarket Gangnam area of Seoul, may have been such a refuge for Seungri, a member of global chart-topper Big Bang. The 28-year-old oversaw publicity for the club and sat on its board, until it shuttered last month amid accusations by police that some on the club’s staff secured prostitutes for VIPs, rape, drug trafficking and drug use.

Seungri has since quit his position with Burning Sun, and apologized to fans over the scandal. With regard to the alleged sharing of illicitly filmed videos, he has promised to “fully engage in (the police) investigation with truthful answers.”

The club did not respond to requests for comment, but a spokesperson had previously said it was “actively cooperating” with police.

Closed off VIP rooms are symbolic of the arms-length relationship between the K-Pop industry and the public, Jung said. Fans are sold a fantasy from a heavily guarded, almost impenetrable system.

Not enough

For some, the K-Pop scandal had been a long time coming.

While some labels that had initially threatened legal action over negative reports about their stars have now apologized, for years they have protected the reputation of their top talent. Previous scandals involving male pop stars have not forced the level of reckoning being seen today.

Another young star named by police in the scandal is Jung Joon-young, who admitted earlier this month to having “filmed women without their consent” and shared it online.

Jung was arrested Thursday and faces up to five years in prison. Speaking to the press outside court, he said he was “truly sorry.”

“I admit to all charges against me. I will not challenge the charges brought by the investigative agency, and I will humbly accept the court’s decision,” he said. “I bow my head in apology to the women who were victimized by my actions.”

The singer has faced similar accusations in the past, with prosecutors dropping a case in 2016 due to “insufficient evidence” against the young singer. Jung did not respond to a request for comment about that case.

The allegations did little to dent Jung’s stardom, with the singer appearing on a popular television show shortly after the scandal.

“The management companies focus all their power on shielding the artists from consequences. The artists end up thinking that their mistakes will not affect them,” said journalist Jung Duk-hyung, the culture expert.

According to Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency, it hasn’t just been labels shielding K-Pop stars. Police officers have also been accused of intervening in investigations to protect stars. This month, South Korea’s head of police Min Gap-ryong vowed to “root out” police collusion no matter the rank of those involved.

Societal issue

K-Pop is not just an industry that only produces male stars – scantily clad female groups including Girls’ Generation and Red Velvet are also wildly popular. But the highly sexualized image of female K-Pop stars has been blamed by some of driving the objectification of women.

“The mistreatment of women in Korean society, particularly the voyeuristic and sexually objectifying treatment of women’s bodies, is deeply enmeshed in K-Pop,” said CedarBough Saeji, an expert in Korean culture and society at the University of British Columbia.

“Videos of male idols often (feature) objectified female dancers, and videos of female idols objectify the idols themselves,” Saeji said. “Young women and men are being sold the idea that a woman’s success is tied to being an object, and this has dangerous ramifications for society.”

South Korea struggles with other gender issues, with the pay gap between men and women among the worst in the developed world. In 2018, the country ranked 30 out of 36 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development nations for women’s employment, even though the country has the highest tertiary education rate of the group for women age 25 to 34.

“You can never feel comfortable in your own body if you’re a woman here,” one spy cam victim told CNN last year. “Just because I’m born as a woman, people objectify me. People objectify my body, even when I’m in the most private place.”

With that sort of harassment so entrenched, experts warn that progress in tackling how men exploit women’s bodies could be slow.