That Julie Heldman feels well enough within herself even to attend the Indian Wells Masters next week should be seen as sufficient victory for one of women’s tennis’ original pioneers.

That she is willing to tell her story on the eve of a first major public appearance in the tennis world in seven years is all the more remarkable, given the emotional strife and mental illness she has both faced and fought.

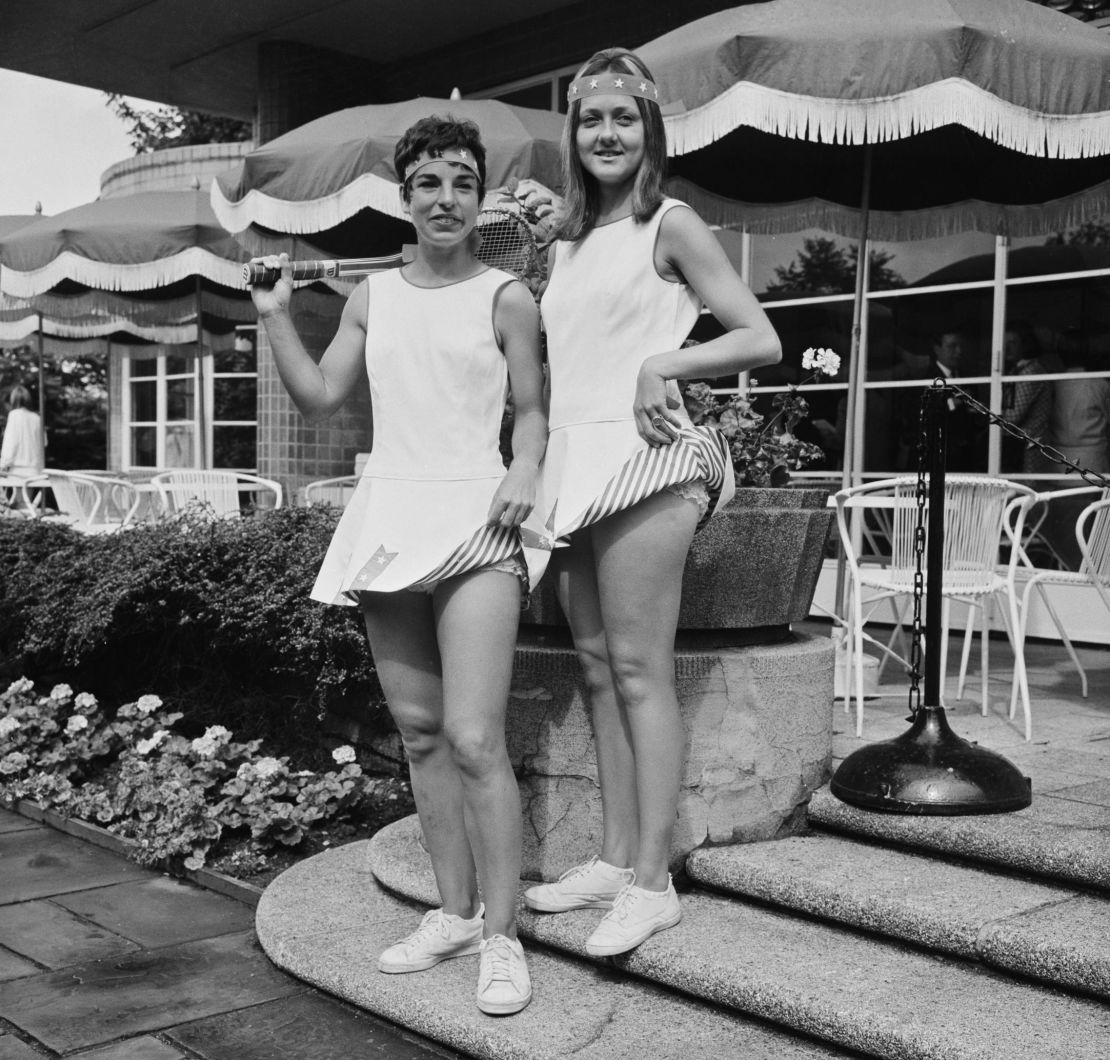

Heldman enjoyed a hugely successful playing career, winning 22 singles titles in an era awash with some of the women’s game’s most iconic names – she can lay claim to victories over Billie Jean King, Margaret Court, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova and Virginia Wade.

Indeed, she sits among the most significant figures in the history of women’s tennis. She was one of the Original Nine, the group of female players who would forego the threat of suspension in order to join the Virginia Slims Circuit, which would eventually form the basis of the WTA Tour.

It was a rebellion; a revolt against the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) overseeing a startling inequality between the prize money paid to male and female players. At the 1970 Italian Open, Ilie Nastase received $3,500 for winning the men’s title, while King took home just $600 for victory in the women’s event.

The women’s game would change further in 1973, with King’s famous Battle of the Sexes victory over Bobby Riggs providing impetus to the burgeoning world of women’s professional tennis. However, it remained a tough school for any female athlete.

“It was very difficult to be taken seriously,” Heldman recalls. “You have to take into account this inherent prejudice – that men should be in charge and that the women should be left to do what they do.

“Each one of us was seen as outcasts. We had muscles at a time when women weren’t meant to have muscles; some of us were gay; some of us were trying to do something that women were supposedly not meant to do.

“We were being attacked so often by the men, so we always had this togetherness – whether we liked each other or not. There was not one other girl in my high school who competed in sport. What happened back then was like another world. We had to be the trailblazers.”

There is, though, a rare complexity to Heldman’s relationship with tennis – a sport in which she was once ranked as the world’s fifth best player, but also one that saw her at her most troubled.

The daughter of Gladys Heldman, an indomitable driving force in the advent of the Virginia Slims tour, hers is a tale of an impossible struggle, centered on the relationship between mother and offspring, emotional abuse and survival amid decades of undiagnosed mental illness.

Since the release of Julie’s memoir last year, Driven – a catalogue of strength in adversity, laying bare the details of a deeply complex life has become easier; the placing of pen to paper serving as a catharsis to a lifetime of bottled-up secrets.

“It is absolutely extraordinary,” Heldman reflects of her upcoming return to the tennis world. From the thrill in her voice, it is clear that she means it.

Given all that she has faced, in many ways, this is a personal triumph that outweighs much of what the former US No.2 achieved with racket in-hand. It says much for the debilitating power of mental illness that someone who thrived in front of a watching audience – both as player and then as broadcaster – has felt so unable to show face.

“It is always more of a struggle for me when there are a lot of people around,” she confesses. “The fact that I can even think about going is pretty thrilling.”

The effects of a childhood of emotional abuse have seen her face a lifetime of difficulty. Long after the end of her playing career, Heldman was diagnosed with bipolar, a disorder that has – at least – given context to some of her difficulties.

While Gladys played an immense role in putting the building blocks in place for the future of the women’s game, her treatment of Julie was cruel. It was motherhood, but without the mothering. Julie would spend the majority of her formative years in isolation, starved of empathy, regularly belittled.

At the same time, however, there is an undying pride in what her mother achieved. Gladys, for her faults, had also suffered from a childhood devoid of maternal compassion. In 2003, she would take her own life.

She was a fearless woman championing the female cause in what was, almost exclusively, a man’s world. Indeed, Gladys would be inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1979 – some feat for a promoter and publisher; she founded the highly influential World Tennis magazine.

“One of the reasons I wanted to write the book was to explain this amazing thing,” Julie explains. “I am completely proud of my mother and all that she did for tennis and all that she achieved.

“Did she love me? I think the answer is yes. But she was, in many ways, incapable of showing empathy. Emotion was very difficult for her to show. Even though some kind of love was lurking underneath, it was very difficult for her to show it in normal ways.”

In her memoir, Julie describes her family as possessing all the characteristics of a cult. She writes of ‘an exceedingly strong leader; isolation from the rest of the world; control, coercion and abuse by the leader.’

It is a cocktail of sentiments that left her with a deep internal conflict. “Differentiating my mother from the woman who did so much for women’s tennis has been, for many years, close to impossible,” she says.

In 1970, Julie would attempt suicide. But, nearly half a century later, it is a time in her life that Heldman, now 73, can look back upon without resentment and with a clarity of what was driving her actions.

“It is important for anyone – those in sport and not – to be able to know that if something is going wrong, that there can be help,” she says, unprompted, with an experienced wisdom and the self-awareness of someone all too aware of the challenges that come with living with mental illness.

“Help can be a friend who listens; help can be someone who’s trained to give guidance. But if you think you’re on your own or if you grow up in an environment where you think that you absolutely have to win, that is going to cause its own damage.

“To find the place to turn to is really important. What I have seen in sport is that, with all the money and with all the people involved, a person might feel like they are getting lost in the cracks. There is always a place somewhere for competitors to turn to.”

Of her own experience, she admits that, at her lowest, she lacked any such safe haven. “After my attempted suicide, I did not know where to go. The only place I knew to go to was back on the tennis court. Yet, nobody had any idea what I was going through. The fact that nobody knew had a massive impact on me.

“In many ways, tennis and winning at tennis and being successful was a saving grace because it gave me the ability to be somebody.

“That’s how I would feel when I won. So, tennis became the one thing that I could turn to; but in itself, tennis was also harmful to me.

“With my mother, if I won she would say that I was the best thing ever, but if I lost I felt terrible. But either way, even if I was the best thing ever, she would often undermine me. It felt like I was living on a razor’s edge – damned if I won and damned if I lost.”

Visit CNN.com/sport for more news, features and videos

The real pull of the career was the traveling, with Heldman’s status among the world’s best seeing her paid to fly to Buenos Aires, South Africa, London and Australia at a time when such a lifestyle was both enviable and uncommon. However, her own personal situation brought with it a pressure that, she says, made life as a professional tennis player difficult to appreciate.

“I enjoyed hitting a hard forehand, I enjoyed constructing a point well. But I didn’t get pure joy out of walking out onto a tennis court,” she admits.

“There was so much wrapped up in tennis, including the fact that my mother dominated the tennis world. She was involved in what I was doing, which felt dangerous to me. People would tell me how wonderful she was, so in some ways, I was stuck in a world where I was almost doubly trapped.

“Nobody [in tennis] knew and nobody in my family spoke about [the abuse],” Heldman recalls. “I did not actually have an understanding myself that what I was going through was significant. That was and has remained one of the most difficult things for me – that feeling that nobody would understand, but then I didn’t either.

“It was, therefore, close to incomprehensible that other people would have considered the way I grew up as being difficult at all. Putting that all together has been the hardest bit.”

Quite simply, having spent much of her childhood alone, hers was the only upbringing she knew. There was no reason to disbelieve it.

The process of beginning to understand, she explains, has been multifaceted. It began with therapy: “I cried for three days,” she says of being told by her therapist that her childhood experiences had not been normal.

“It was only a few sessions in that she explained that other families would not have treated me this way. She told me that this didn’t have to happen.”

Perhaps, though, what is most significant in explaining Heldman’s lifelong struggle with herself is that she has come to understand her own set of circumstances.

Not only can she now comprehend an often tearful and lonely youth, but she has been able to recognize the root of what she describes as her “volatility” on the court.

Heldman pauses as she recalls an anecdote from the recent past. “One of the old players said to me: ‘I like you more now than I used to’, and I began to understand that I could have been jarring and I could have been difficult.

“That was because I didn’t understand what was going on and because I wasn’t receiving help a lot of the time. It was hard to be otherwise – I never wanted to be jarring and difficult.”

It is a story that summarizes all that bipolar brings – the episodes of depression that accompany the periods of manic energy.

“Mania, for me, feels like second nature,” Heldman explains. “I have always pushed too hard, so I do not know that things are going wrong if I start functioning at a very high level. It hooks into what I do, which is to be driven and to do as much as possible.

“Depression, on the other hand, is very clear to me. When I start feeling bad, I often stop being able to function – even to get out of bed or to talk to people on the phone. Using a telephone can feel daunting. There were many years when I had no clue as to why it was happening.

“It happened sometimes when I was playing on the tennis tour, which was difficult because I couldn’t function. The upside can be so startling, but the downside can be terrible.

“If I can’t function, I can’t succeed. If I can’t succeed, I can’t feel good. It has always been that way.”

READ: Laslo Djere wins first ATP Tour title, dedicates victory to his late parents

Alongside her childhood trauma and the inherent stresses of tournament tennis, she counts her bipolar – and the harmful effects of her medication – among the four major culprits of her mental struggle.

Yet, Heldman also pinpoints the revelation of her bipolar as another crucial step on her pathway towards comprehending the events of her own existence. “My brain chemistry was going in different directions at the same time,” Heldman explains. “They said I had a dual diagnosis – both the childhood abuse and the bipolar.”

With the help of therapy, it was also a diagnosis that has allowed Heldman to put together the pieces of her lifelong jigsaw.

“I can look back now and see why I went through certain things,” she says. “I thought about why I used to get upset so often and why I used to think that I didn’t have friends. The truth is that I didn’t have friends because I didn’t know people. I grew up without others.

“It’s why I got upset so often – something was deeply churning inside of me and it was something that I did not understand. There are a lot of people out there on the tennis tour who have ‘stuff’ [that drives them]. Mine was my story and what happened to me was severe.”

With the passing of time, Heldman has found a way to add nuance to the win-at-all-costs mantra that was force-fed into her psyche as a child and that heightened the issues she has faced in adulthood.

A cataclysmic breakdown that forced her to retire from the business she co-controlled alongside her husband, Bernie, has also – paradoxically, perhaps – played its part.

“Once that happened, I couldn’t do much,” she explains. “It taught me a lesson in itself – that I could have a life even though I wasn’t achieving, that there was a lot to be joyful for in waking up every day and having a family.

“Before, I felt great if I won, but I immediately felt lousy because I’d feel like something awful was about to happen. Now, I can sit back and understand that I did some good things. I can finally look at that and realize – I’m proud of what I did and I’m able to feel that pride now that I feel more at peace.”

As a captivating chat comes towards its end, Heldman briefly goes silent as she ponders the notion of regret. Could her career and her adult life have followed a different path had she belonged to a different time? Could the modern-day appreciation of mental illness have provided her with a greater and earlier understanding of her own troubles? Could an alternative childhood have led to an even greater tennis career?

Her response – when it comes – is fascinating. It highlights, perhaps better than any other moment in a truly heartening hour, the value of Heldman’s own long-term introspection.

“It was an era when there wasn’t much help,” she acknowledges. “It is hard to undo the daily indignities of a child. Once it happens every single day of your life, it is hard to think that you could have been a different person.

“I was that driven child who had to win and who felt better from winning. Had I had a different life, who knows? I wonder whether I would have won so much had I not been so driven.”