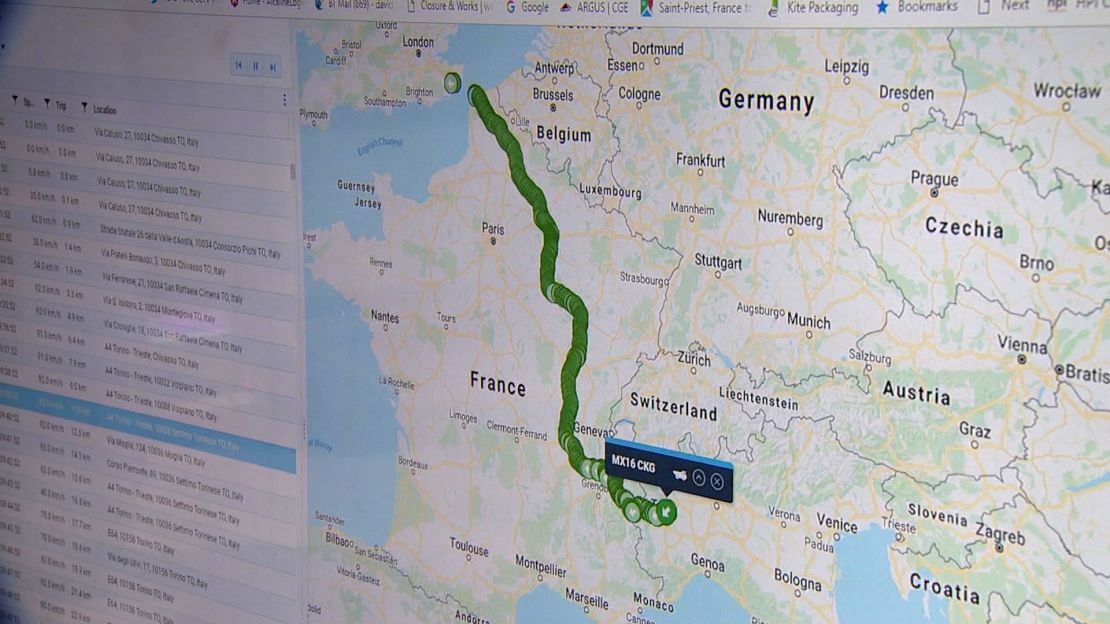

If everything goes according to plan, truck driver Gordon Terry needs 44 hours to haul a shipment of car parts from Turin, Italy to Jaguar Land Rover’s factory outside of Liverpool.

“By law, 10 hours is the most you can drive in one day,” Terry said as he pointed to the tachograph which records his time on the road. The driver for Alcaline International Haulage Company gets as far as he can — usually about 500 miles — before stopping for the night.

Terry has been driving the heavily trafficked route from Italy’s industrial heartland to auto factories in the north of England for 25 years. Many of the parts he carries are bolted onto vehicles within hours of their delivery in Britain, making him an essential part of the just-in-time manufacturing process used by companies like BMW (BMWYY), Airbus (EADSF), Nissan (NSANF), and Jaguar Land Rover (JLR).

A disorderly Brexit would cause customs checks at the UK border and disrupt the finely tuned manufacturing system. The companies have warned of immediate damage to their supply chains, while new trade barriers and higher costs after March 29 could eventually force manufacturers to rethink their business in the United Kingdom.

“[The] worst case scenario would be just blockades, vehicles parked up because we don’t know what’s going on,” said David Zaccheo, operations director at Alcaline. “It’s difficult for me to obviously comment on that because we’re not sure ourselves what’s gonna happen.”

The problem at Dover

The biggest crunch point for drivers like Terry is expected to be the English Channel crossing between Dover and the French town of Calais. The port of Dover handled 2.5 million trucks in 2018 and another 1.7 million passed through the nearby Eurotunnel under the channel.

Britain’s EU membership means trucks currently zip cross the border. But customs checks will be needed if the United Kingdom leaves the European Union without an exit agreement in place.

“Even adding a couple of minutes for the basic checks to see if the paperwork has been filed correctly will [cause trucks to] tail back up to about 20 kilometers [12 miles] on either side of the border,” said Alex Veitch, head of global policy for the UK Freight Transport Association.

Some of the largest manufacturing companies operating in Britain have warned of dire consequences if there are delays at the border.

Ford (F) estimates that a disorderly Brexit would cost it $800 million in 2019. JLR, owned by India’s Tata Motors (TTM), has warned it would wipe out £1.2 billion ($1.6 billion) a year in profit.

“If one part is not at the right time, on the right position, next to the assembly line, we are facing a challenge,” JLR CEO Ralf Speth told Sky News last year. “That is a huge risk.”

BMW has already decided to shut its Mini factory in Oxford for a month of maintenance immediately after Brexit because it can’t be sure that parts will be delivered.

“As a responsible business, we are looking at our options and taking steps to make sure we’re prepared for a worst case scenario,” BMW told CNN Business. “This includes any potential port delays.”

The consequences could stretch far into the future. Aerospace giant Airbus said last month that it could redirect future investment away from its factories in Britain if trade links and supply chains are not protected.

“I’m not surprised that [companies] are probably looking at relocating to areas where that delay does not exist,” said Veitch.

By land, sea or air

Across the channel, Port of Calais CEO Jean-Marc Puissesseau and his team have spent $6.8 million to build a holding area where 250 trucks can be parked for customs checks.

He downplayed talk of potential delays. Trucks that arrive at the border with the correct paperwork will be waived through customs, he said, while those with incomplete or inaccurate documents will be directed to the holding area.

“There is no reason to have a traffic jam, to have a big congestion of traffic,” said Puissesseau.

Transport companies and trade experts think the French executive is too optimistic. They say that businesses are not prepared for a new customs regime, mainly because they haven’t been told how the system will function.

Veitch said the port doesn’t have the technology needed to check drivers’ paperwork in real time. And the holding area for 250 trucks won’t be nearly big enough, according to Alcaline’s Zaccheo.

Zaccheo, whose trucks make 10,000 border crossings a year, is preparing for the worst. He recently purchased a helicopter to help circumvent border delays and rush small parts to UK factories.

“If the vehicles were to be stopped in Calais or Dover for customs checks and all of a sudden the lines stopped, then obviously time is of the essence,” Zaccheo said. “The helicopter can set off, recover those parts and fly straight to the plant.”

‘It’s a reality’

Britain is set to leave the European Union in less than 50 days, but there’s still no clarity on its exit plan. Terry, the truck driver, isn’t worried about a messy divorce.

“We will rebuild,” he said. “It will create more industry. It will create more work for youngsters.”

Puissesseau is confident that Terry’s trips across the channel won’t be disrupted no matter what happens with Brexit. Still, he said the wounds caused by the separation run deep.

“It’s a pity, really a pity, to know that just in front of us, 36 kilometers [22 miles], it will be a third country,” Puissesseau said, pointing across the channel to the white cliffs of Dover. “I still can’t believe it, but it’s a reality.”