It sits on the banks of the Monongahela River like a monstrous monument to extinction.

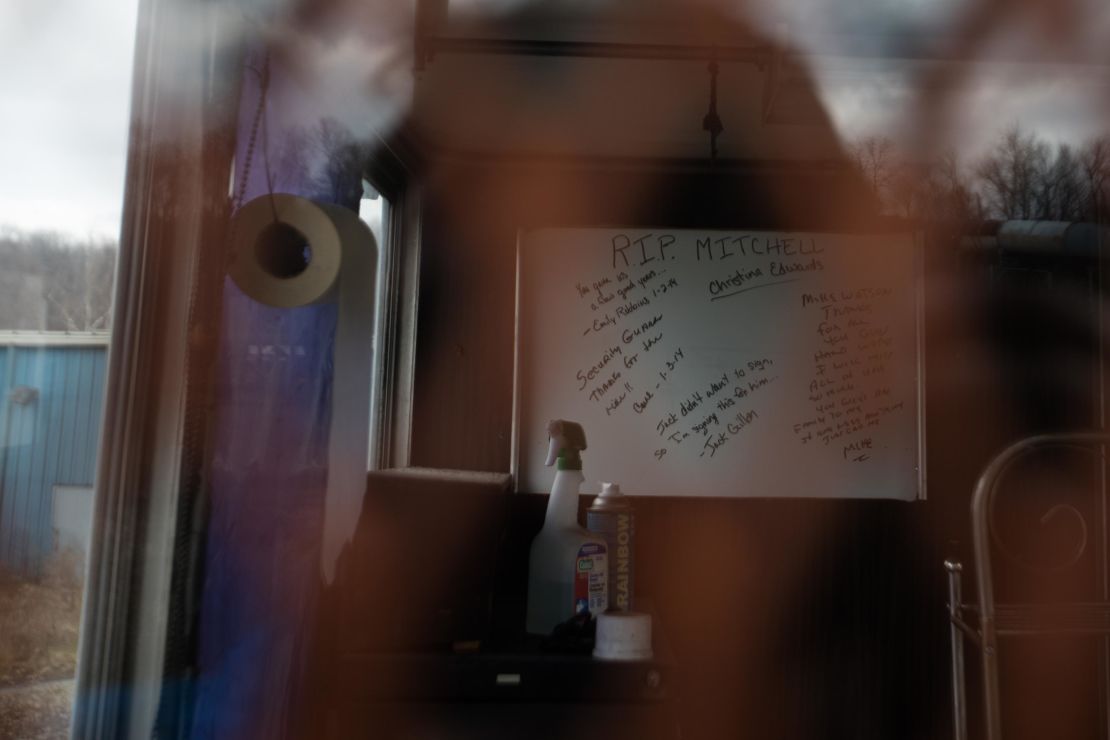

With no fire in its belly and no smoke in its stacks, the rusting power plant provides only one sign of its former inhabitants, scribbled on a white board in a padlocked guard booth.

“RIP Mitchell,” the handwriting reads. “You gave us a good few years.”

The Mitchell Power Station, just south of Pittsburgh, actually turned Pennsylvania coal into power for a good 65 years before the discovery of cheaper, cleaner forms of energy.

As fracked natural gas and renewables like wind and solar undercut the price of coal, both Mitchell and the nearby Hatfield’s Ferry power plants were deactivated on the same day in 2013.

Many in this corner of coal country blamed Obama-era regulations on their demise, so when a candidate named Donald Trump promised to end a so-called “war on coal,” they were ready to believe.

“We are putting our great coal miners back to work,” he repeated to rally crowds waving “Trump Digs Coal” signs. “I’m coal’s last shot.”

But thanks largely to free-market forces, more coal-fired power plants have been deactivated in Trump’s first two years in office then in Obama’s entire first term. When asked about the President’s claim to be the savior of coal, veteran miner and industry consultant Art Sullivan bristles.

“He’s trying to get their votes,” he says, standing by the fenced-off entrance to a mine not far from Mitchell where he once served as Face Boss, a coal industry term for managers. “He’s lying to them.”

For 52 years, Sullivan worked in mines around the world and, like many in western Pennsylvania, he remembers Hillary Clinton’s 2016 Ohio town hall where she said, “We’re going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business.”

In her book “What Happened,” Clinton devoted an entire chapter to the gaffe, which eclipsed her early campaign promise to provide a $30 billion aid package to struggling coal communities.

Sullivan had his own thoughts. “What you need to say to coal miners is ‘We’re going to figure out a way to give you better, safer, healthier jobs.’ These guys and the few gals are simply too good. They are too capable to simply say that we don’t need you,” he said.

Looking for a cure

“They wanted hope,” Blair Zimmerman says of his fellow miners in Greene County, Pennsylvania, who put their faith in Trump. “If someone that has a sickness or a cancer and the doctor says ‘I can cure that,’ they believe … I can’t blame them or question them for trusting (Trump).”

Now a county commissioner, Zimmerman is part of a local group hoping to lure natural gas investors from Texas to drill in Pennsylvania and he scoffs at the Trump administration’s efforts to deregulate coal-fired power plants. “It will help this much,” he says, holding his fingers an inch apart. “But it won’t bring back coal as king.”

Trump’s EPA – now led by former coal lobbyist Andrew Wheeler – recently moved to lift Obama-era caps on how much poisonous mercury and heat-trapping carbon power plants would be allowed to pump into the sky. The argument was that less regulation could boost the coal industry and perhaps lead to cheaper electricity.

The 2012 regulations should not be considered “appropriate and necessary,” the EPA said, even though utility companies already spent billions installing pollution control technology and the agency’s own reports say that the rule changes could lead to as many as 1,400 more premature deaths a year by 2030.

‘Nothing can stop’ transition to renewables

The EPA also joined 11 other national agencies – from the Pentagon to the Smithsonian – in the alarming Black Friday report that warns of a catastrophic future unless drastic steps are taken to slow down man-made climate change.

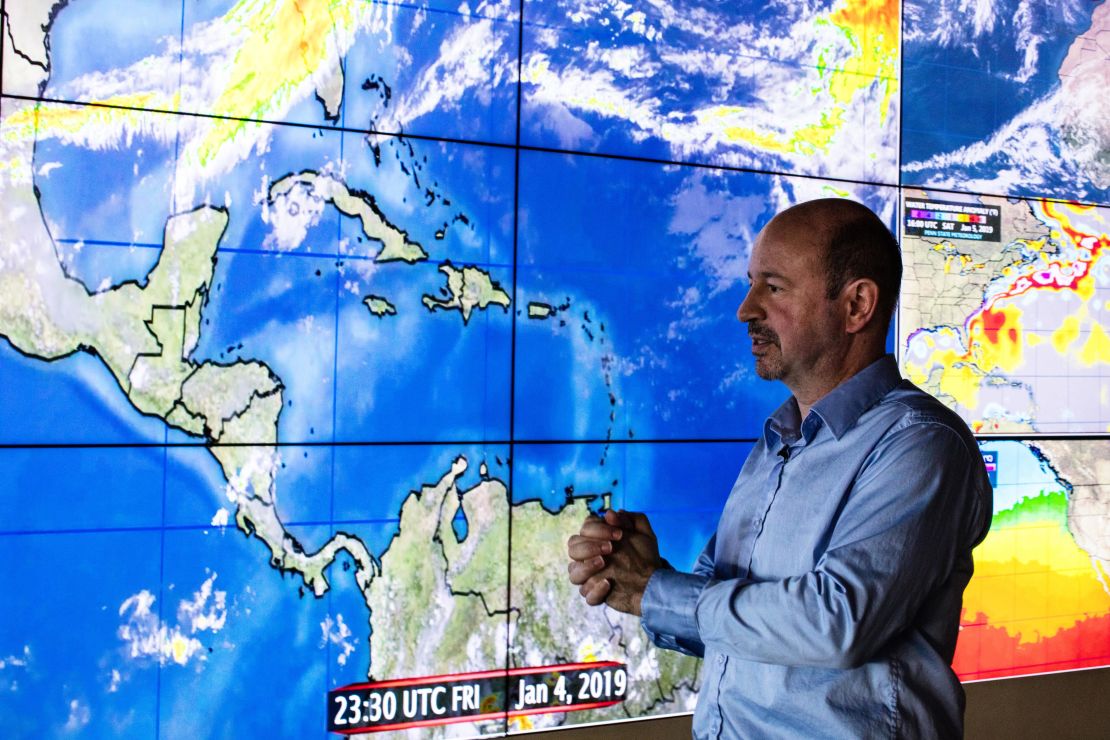

“I think there’s enough resilience in the (Earth’s) system that we can withstand one four-year term of Donald Trump,” says Penn State climatologist Michael Mann. “I’m not sure we can withstand two.”

Mann is among the chorus of international climate scientists who argue that to save life on Earth as we know it, wealthy nations like the US need to switch to carbon-free electricity by 2030. This would mean 80% of current coal reserves would need to stay in the ground, he wrote.

“We’ve undergone transitions like this before,” Mann says on another unseasonably warm winter’s day in State College, across Pennsylvania from the Mitchell Power Station.

“We got off whale oil because something better came along. That was fossil fuels,” he says. “Now something better has come along and that’s renewable energy and there’s nothing that can stop that transition.”